Improper integral

In the simplest case of a real-valued function of a single variable integrated in the sense of Riemann (or Darboux) over a single interval, improper integrals may be in any of the following forms: The first three forms are improper because the integrals are taken over an unbounded interval.

This requirement avoids the ambiguous case of adding positive and negative infinities (i.e., the "

The previous remarks about indeterminate forms, iterated limits, and the Cauchy principal value also apply here.

can have more discontinuities, in which case even more limits would be required (or a more complicated principal value expression).

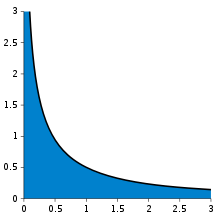

The original definition of the Riemann integral does not apply to a function such as

on the interval [1, ∞), because in this case the domain of integration is unbounded.

The problem here is that the integrand is unbounded in the domain of integration.

Integrated, say, from 1 to 3, an ordinary Riemann sum suffices to produce a result of π/6.

However, any finite upper bound, say t (with t > 1), gives a well-defined result, 2 arctan(√t) − π/2.

Similarly, the integral from 1/3 to 1 allows a Riemann sum as well, coincidentally again producing π/6.

Replacing 1/3 by an arbitrary positive value s (with s < 1) is equally safe, giving π/2 − 2 arctan(√s).

Combining the limits of the two fragments, the result of this improper integral is This process does not guarantee success; a limit might fail to exist, or might be infinite.

An improper integral converges if the limit defining it exists.

For instance However, other improper integrals may simply diverge in no particular direction, such as which does not exist, even as an extended real number.

, since the double limit is infinite and the two-integral method yields an indeterminate form,

In this case, one can however define an improper integral in the sense of Cauchy principal value: The questions one must address in determining an improper integral are: The first question is an issue of mathematical analysis.

The second one can be addressed by calculus techniques, but also in some cases by contour integration, Fourier transforms and other more advanced methods.

This often happens when the function f being integrated from a to c has a vertical asymptote at c, or if c = ∞ (see Figures 1 and 2).

Such cases are "properly improper" integrals, i.e. their values cannot be defined except as such limits.

An improper integral may diverge in the sense that the limit defining it may not exist.

In this case, there are more sophisticated definitions of the limit which can produce a convergent value for the improper integral.

One summability method, popular in Fourier analysis, is that of Cesàro summation.

The integral is Cesàro summable (C, α) if exists and is finite (Titchmarsh 1948, §1.15).

The value of this limit, should it exist, is the (C, α) sum of the integral.

The definition is slightly different, depending on whether one requires integrating over an unbounded domain, such as

is a non-negative function that is Riemann integrable over every compact cube of the form

containing A: More generally, if A is unbounded, then the improper Riemann integral over an arbitrary domain in

is defined as the limit: If f is a non-negative function which is unbounded in a domain A, then the improper integral of f is defined by truncating f at some cutoff M, integrating the resulting function, and then taking the limit as M tends to infinity.

A more general function f can be decomposed as a difference of its positive part

has one, in which case the value of that improper integral is defined by In order to exist in this sense, the improper integral necessarily converges absolutely, since

has unbounded intervals for both domain and range.

converges, since both left and right limits exist, though the integrand is unbounded near an interior point.

![{\displaystyle \int _{-1}^{1}{\frac {dx}{\sqrt[{3}]{x^{2}}}}=6}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd73b4f0af904c14ed328dffa7434256e9f32eca)