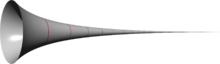

Gabriel's horn

A Gabriel's horn (also called Torricelli's trumpet) is a type of geometric figure that has infinite surface area but finite volume.

The name refers to the Christian tradition where the archangel Gabriel blows the horn to announce Judgment Day.

The properties of this figure were first studied by Italian physicist and mathematician Evangelista Torricelli in the 17th century.

[1] Torricelli's own name for it is to be found in the Latin title of his paper De solido hyperbolico acuto, written in 1643, a truncated acute hyperbolic solid, cut by a plane.

[1] Although credited with primacy by his contemporaries, Torricelli was not the first to describe an infinitely long shape with a finite volume or area.

[4] Oresme had posited such things as an infinitely long shape constructed by subdividing two squares of finite total area 2 using a geometric series and rearranging the parts into a figure, infinitely long in one dimension, comprising a series of rectangles.

Torricelli's original non-calculus proof used an object, slightly different to the aforegiven, that was constructed by truncating the acute hyperbolic solid with a plane perpendicular to the x axis and extending it from the opposite side of that plane with a cylinder of the same base.

and integrating along the x axis, Torricelli proceeded by calculating the volume of this compound solid (with the added cylinder) by summing the surface areas of a series of concentric right cylinders within it along the y axis and showing that this was equivalent to summing areas within another solid whose (finite) volume was known.

[9] In modern terminology this solid was created by constructing a surface of revolution of the function (for strictly positive b)[9]

An acute hyperbolic solid, infinitely long, cut by a plane [perpendicular] to the axis, together with the cylinder of the same base, is equal to that right cylinder of which the base is the latus versum (that is, the axis) of the hyperbola, and of which the altitude is equal to the radius of the basis of this acute body.Torricelli showed that the volume of the solid could be derived from the surface areas of this series of concentric right cylinders whose radii were

and the nested surfaces of the cylinders (filling the volume of the solid) are thus equivalent to the stacked areas of the circles of radius

:[9] Propterea omnes simul superficies cylindricae, hoc est ipsum solidum acutum

[3] The use of Cavalieri's indivisibles in this proof was controversial at the time and the result shocking (Torricelli later recording that Gilles de Roberval had attempted to disprove it); so when the Opera geometrica was published, the year after De solido hyperbolico acuto, Torricelli also supplied a second proof based upon orthodox Archimedean principles showing that the right cylinder (height

[3] Ironically, this was an echo of Archimedes' own caution in supplying two proofs, mechanical and geometrical, in his Quadrature of the Parabola to Dositheus.

[11] When the properties of Gabriel's horn were discovered, the fact that the rotation of an infinitely large section of the xy plane about the x axis generates an object of finite volume was considered a paradox.

(see Particular values of the Riemann zeta function for more detail on this result) The apparent paradox formed part of a dispute over the nature of infinity involving many of the key thinkers of the time, including Thomas Hobbes, John Wallis, and Galileo Galilei.

In lecture 16 of his 1666 Lectiones, Isaac Barrow held that Torricelli's theorem had constrained Aristotle's general dictum (from De Caelo book 1, part 6) that "there is no proportion between the finite and the infinite".

[13] Barrow had been adopting the contemporary 17th-century view that Aristotle's dictum and other geometrical axioms were (as he had said in lecture 7) from "some higher and universal science", underpinning both mathematics and physics.

[15] Thus Torricelli's demonstration of an object with a relation between a finite (volume) and an infinite (area) contradicted this dictum, at least in part.

[15] Others used Torricelli's theorem to bolster their own philosophical claims, unrelated to mathematics from a modern viewpoint.

[16] Ignace-Gaston Pardies in 1671 used the acute hyperbolic solid to argue that finite humans could comprehend the infinite, and proceeded to offer it as proof of the existences of God and immaterial souls.

[16] Hobbes' and Wallis' dispute was actually within the realm of mathematics: Wallis enthusiastically embracing the new concepts of infinity and indivisibles, proceeding to make further conclusions based upon Torricelli's work and to extend it to employ arithmetic rather than Torricelli's geometric arguments; and Hobbes claiming that since mathematics is derived from real world perceptions of finite things, "infinite" in mathematics can only mean "indefinite".

[18] These led to strongly worded letters by each to the Royal Society and in Philosophical Transactions, Hobbes resorting to namecalling Wallis "mad" at one point.

[20] Wallis argued that there existed geometrical shapes with finite area/volume but no centre of gravity based upon Torricelli, stating that understanding this required more of a command of geometry and logic "than M. Hobs [sic] is Master of".

Torricelli's theorem does not talk about a layer of finite width on the outside of the solid, which in fact would have infinite volume.

[26][27] Physical paint travels at a bounded speed and would take an infinite amount of time to flow down.

[29] This also applies to "mathematical" paint of zero thickness if one does not additionally postulate it flowing at infinite speed.

In response to Torricelli's theorem, after learning of it from Marin Mersenne, Christiaan Huygens and René-François de Sluse wrote letters to each other about extending the theorem to other infinitely long solids of revolution; which have been mistakenly identified as finding such a converse.

[31] Jan A. van Maanen, professor of mathematics at the University of Utrecht, reported in the 1990s that he once mis-stated in a conference at Kristiansand that de Sluse wrote to Huygens in 1658 that he had found such a shape:[32] evi opera dedicator meansura vasculie, pondere non magni, quod interim helluo nullus ebibat (I give the measurements of a drinking glass (or vase), that has a small weight, but that even the hardest drinker could not empty.

[32] Professor van Maanen realized that this was a misinterpretation of de Sluse's letter, and that what de Sluse was actually reporting that the solid "goblet" shape, formed by rotating the cissoid of Diocles and its asymptote about the y axis, had a finite volume (and hence "small weight") and enclosed a cavity of infinite volume.