In Search of Lost Time

The rejection of this book will remain the most serious mistake ever made by the NRF and, since I bear the shame of being very much responsible for it, one of the most stinging and remorseful regrets of my life (Tadié, 611).The novel recounts the experiences of the Narrator (who is never definitively named) while he is growing up, learning about art, participating in society, and falling in love.

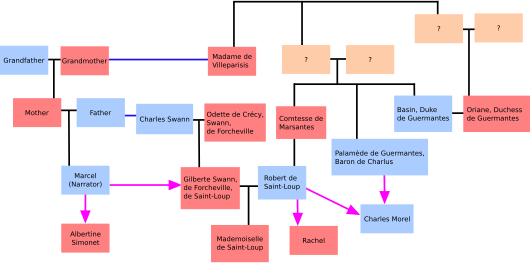

He remembers being in his room in the family's country home in Combray, while downstairs his parents entertain their friend Charles Swann, an elegant man of Jewish origin with strong ties to society.

The Verdurins host M. de Forcheville; their guests include Cottard, a doctor; Brichot, an academic; Saniette, the object of scorn; and a painter, M. Biche.

The Narrator ponders Saint-Loup's attitude towards his aristocratic roots, and his relationship with his mistress, a mere actress whose recital bombed horribly with his family.

One day, the Narrator sees a "little band" of teenage girls strolling beside the sea, and becomes infatuated with them, along with an unseen hotel guest named Mlle.

After noting the landscape and his state of mind while sleeping, the Narrator meets and attends dinners with Saint-Loup's fellow officers, where they discuss the Dreyfus Affair and the art of military strategy.

Swann arrives, and the Narrator remembers a visit from Morel, the son of his uncle Adolphe's valet, who revealed that the "lady in pink" was Mme.

de Stermaria, but she abruptly cancels, although Saint-Loup rescues him from despair by taking him to dine with his aristocratic friends, who engage in petty gossip.

The next day, at the Guermantes's dinner party, the Narrator admires their Elstir paintings, then meets the cream of society, including the Princess of Parma, who is an amiable simpleton.

He fakes a preference for her friend Andrée to make her become more trustworthy, and it works, but he soon suspects her of knowing several scandalous women at the hotel, including Léa, an actress.

On the train with him is the little clan: Brichot, who explains at length the derivation of the local place-names; Cottard, now a celebrated doctor; Saniette, still the butt of everyone's ridicule; and a new member, Ski.

Charlus reviews Morel's betrayals and his own temptation to seek vengeance; critiques Brichot's new fame as a writer, which has ostracized him from the Verdurins; and admits his general sympathy with Germany.

Inside, while waiting in the library, he discerns their meaning: by putting him in contact with both the past and present, the impressions allow him to gain a vantage point outside time, affording a glimpse of the true nature of things.

Although parts of the novel could be read as an exploration of snobbery, deceit, jealousy and suffering, and although it contains a multitude of realistic details, the focus is not on the development of a tight plot or of a coherent evolution but on a multiplicity of perspectives and on the formation of experience.

The protagonists of the first volume (the narrator as a boy and Swann) are, by the standards of 19th-century novels, remarkably introspective and passive, nor do they trigger action from other leading characters; to contemporary readers, reared on Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo and Leo Tolstoy, they would not function as centers of a plot.

Although Proust wrote contemporaneously with Sigmund Freud, with there being many points of similarity between their thought on the structures and mechanisms of the human mind, neither author read the other.

[6] The madeleine episode reads: No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me.

And all from my cup of tea.Gilles Deleuze believed that the focus of Proust was not memory and the past but the narrator's learning the use of "signs" to understand and communicate ultimate reality, thereby becoming an artist.

The first arrival of this theme comes in the Combray section of Swann's Way, where the daughter of the piano teacher and composer Vinteuil is seduced, and the narrator observes her having lesbian relations in front of the portrait of her recently deceased father.

The first chapter of "Cities of the Plain" ("Sodom and Gomorrah") includes a detailed account of a sexual encounter between M. de Charlus, the novel's most prominent male homosexual, and his tailor.

Proust does not designate Charlus's homosexuality until the middle of the novel, in "Cities"; afterwards the Baron's ostentatiousness and flamboyance, of which he is blithely unaware, completely absorb the narrator's perception.

In 1949, the critic Justin O'Brien published an article in the Publications of the Modern Language Association called "Albertine the Ambiguous: Notes on Proust's Transposition of Sexes", in which he proposed that some female characters are best understood as actually referring to young men.

"[15] Edith Wharton wrote that "Every reader enamoured of the art must brood in amazement over the way in which Proust maintains the balance between these two manners—the broad and the minute.

According to Cambridge University Press, "Proust's reception during his lifetime is always set against the backdrop of often-hostile criticism, frequently based on the myth of the sickly, reclusive snob writing from the safety of his cork-lined room.

[18] Vladimir Nabokov, in a 1965 interview, named the greatest prose works of the 20th century as, in order, "Joyce's Ulysses, Kafka's Transformation [usually called The Metamorphosis], Bely's Petersburg, and the first half of Proust's fairy tale In Search of Lost Time".

[21] Michael Dirda wrote that "To its admirers, it remains one of those rare encyclopedic summas, like Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, the essays of Montaigne or Dante's Commedia, that offer insight into our unruly passions and solace for life's miseries.

"[25] Another hostile critic is Kazuo Ishiguro, who said in an interview: "To be absolutely honest, apart from the opening volume of Proust, I find him crushingly dull.

"[26] Since the publication in 1992 of a revised English translation by The Modern Library, based on a new definitive French edition (1987–89), interest in Proust's novel in the English-speaking world has increased.

The Penguin volumes each provide an extensive set of brief, non-scholarly endnotes that help identify cultural references perhaps unfamiliar to contemporary English readers.

Since 2013, Yale University Press has been publishing a new revision of Scott Moncrieff's translation, edited and annotated by William C. Carter, at the rate of one volume every two or three years.