Inca road system

[3]: 634 The network was composed of formal[4] roads carefully planned, engineered, built, marked and maintained; paved where necessary, with stairways to gain elevation, bridges and accessory constructions such as retaining walls, and water drainage systems.

[6] The road system allowed for the transfer of information, goods, soldiers and persons, without the use of wheels, within the Tawantinsuyu or Inca Empire throughout a territory covering almost 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi)[7] and inhabited by about 12 million people.

[1] Different organizations such as UNESCO and IUCN have been working to protect the network in collaboration with the governments and communities of the six countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina) through which the Great Inca Road passes.

[9] I believe that, since the memory of people, it has not been read of such a greatness as this road, made through deep valleys and high peaks, snow covered mountains, marshes of water, live rock and beside furious rivers; in some parts it was flat and paved, on the slopes well made, by the mountains cleared, by the rocks excavated, by the rivers with walls, in the snows with steps and resting places; everywhere it was clean, swept, clear of debris, full of dwellings, warehouses for valuable goods, temples of the Sun, relay stations that were on this road.The Tawantinsuyu, which integrated the current territories of Peru, continued towards the north through present-day Ecuador, reaching the northernmost limits of the Andean mountain range in the region of Los Pastos in Colombia; by the South, it penetrated down to the Mendoza and Atacama lands, in the southernmost reaches of the Empire, corresponding currently with Argentine and Chilean territories.

[10] As indicated by Hyslop, "The main route of the sierra (mountains) that passes through Quito, Tumebamba, Huánuco, Cusco, Chucuito, Paria and Chicona to the Mendoza River, has a length of 5,658 km."

[12] Recent investigations carried out under the Proyecto Qhapaq Ñan, sponsored by the Peruvian government and basing also on previous research and surveys, suggest with a high degree of probability that another branch of the road system existed on the east side of the Andean ridge, connecting the administrative centre of Huánuco Pampa with the Amazonian provinces and having a length of about 470 kilometres (290 mi).

The route towards the North was the most important in the Inca Empire, as shown by its constructive characteristics: a width ranging between 3 and 16 m[11]: 108 and the size of the archaeological vestiges that mark the way both in its vicinity and in its area of influence.

It is not coincidental that this path goes through and organizes the most important administrative centers of the Tawantinsuyu outside Cusco, such as Vilcashuamán, Xauxa, Tarmatambo, Pumpu, Huánuco Pampa, Cajamarca and Huancabamba, in current territories of Peru; and Ingapirca, Tomebamba or Riobamba in Ecuador.

[15] The route of Qollasuyu leaves Cusco and points towards the South, splitting into two branches to skirt Lake Titicaca (one on the east and one the west coast) that join again to cross the territory of the Bolivian Altiplano.

One branch headed towards the current Mendoza region of Argentina, while the other penetrated the ancient territories of the Diaguita and Atacama people in Chilean lands, who had already developed basic road networks.

[15] Contisuyu roads allowed to connect Cusco to coastal territories, in what corresponds to the current regions of Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna, in the extreme Peruvian south.

They penetrated into the territories of the Ceja de Jungla or Amazonian Andes leading to the Amazon rainforest, where conditions are more difficult for the conservation of archaeological evidences.

The Incas had a predilection for the use of the Altiplano, or puna areas, for displacement, seeking to avoid contact with the populations settled in the valleys, and project, at the same time, a straight route of rapid communication.

As an example, the administrative center of Huánuco Pampa includes 497 collcas, which totaled as much as 37,100 cubic metres (1,310,000 cu ft) and could support a population of between twelve and fifteen thousand people.

He states: «soldiers, porters, and llama caravans were prime users, as were the nobility and other individuals on official duty… Other subjects were allowed to walk along the roads only with permission…» Nevertheless, he recognizes that «there was also an undetermined amount of private traffic … about which little is known».

Only about 25 percent of this network is still visible today, the rest having been destroyed by wars (conquest, uprising, independence or between nations), the change in the economic model which involved abandoning large areas of territory, and finally the construction of modern infrastructure, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which led to the superposition of new communication channels in the outline of pre-Hispanic roads.

To the south there are abundant remains, around Mendoza in Argentina and along the Maipo river in Chile, where the presence of forts marks the line of the road at the southernmost point of the Empire.

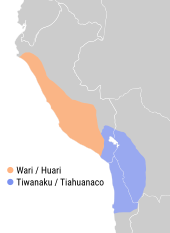

Much of the system was the result of the Incas claiming exclusive right over numerous traditional routes, some of which had been constructed centuries earlier, mostly by the Wari empire in the central highlands of Peru and the Tiwanaku culture.

Many new sections of the road were built or upgraded substantially by the Incas: the one through Chile's Atacama desert and the one along the western margin of Lake Titicaca serve as two examples.

[32] The historical stage of the Empire begun around 1438 when, having settled the disputes with local populations around Cusco, the Incas started the conquest of the coastal valleys from Nasca to Pachacamac and the other regions of Chinchaysuyu.

[13] Their strategy involved modifying or constructing a road structure that would ensure the connection of the incorporated territory with Cusco and with other administrative centers, allowing the displacement of troops and officials.

[1] A key factor in the dismantling of the network at the subcontinental level was the opening of new routes to connect the emerging production centers (estates and mines) with the coastal ports.

In this context, only those routes that covered the new needs were used, abandoning the rest, particularly those that connected to the forts built during the advance of the Inca Empire or those that linked the agricultural spaces with the administrative centres.

Even the new agriculture, derived from Spain, consisting mainly of cereals, changed the appearance of the territory, which was sometimes transformed, cutting and joining several andenes (farming terraces), which in turn reduced the fertile soil due to erosion form rain.

In the case of Peru, the territorial structure established by the Colony was maintained while the link between the production of the mountains and the coast was consolidated under a logic of extraction and export.

At the end of the eighteenth century, large estates were developed for the supply of raw materials to international markets, together with guano, so the maritime ports of Peru took on special relevance[1] and intense activity requiring an adequate accessibility from the production spaces.

Some parts of the Inca roads were still in use in the south of the Altiplano giving access to the main centers for the production of alpaca and vicuña wools, which were in high demand in the international markets.

On the coast and in the mountains, the availability of construction materials such as stone and mud for preparing adobes allowed to build walls on both sides of the road, to isolate it from agricultural land so that the walkers and caravans traveled without affecting the crops.

On rocky outcrops the road became narrower, adapting to the orography with frequent turns and retaining walls, but on particularly steep slopes flights of stairs or ramps were built or carved in the rock.

[41][42] Garcilaso de la Vega[14] underlines the presence of infrastructure on the Inca road system where all across the Empire lodging posts for state officials and chasqui messengers were ubiquitous, well-spaced and well provisioned.