Peruvian War of Independence

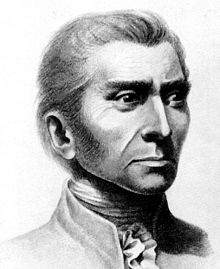

Viceroy José Fernando de Abascal y Sousa made Peru a base for counterrevolution and won military victories in the south frontier in 1809, in La Paz revolution and 1811 in the Battle of Guaqui.

The Liberating Expedition of Peru, under the command of Argentine General José de San Martín, landed on the Peruvian coast from Chile.

[citation needed] The struggle for independence in 18th and 19th century Peru was a complex and multifaceted process, marked by indigenous uprisings, colonial resistance, and the emergence of strong regional identities.

Against the backdrop of Spanish colonial rule, women found themselves thrust into positions of leadership and responsibility within their households as husbands fled or were absent.

This period of turmoil and change not only reshaped the socio-political landscape of Peru but also underscored the resilience and adaptability of its people, particularly women, in navigating the tumultuous path towards independence.

By examining the intersecting narratives of colonial resistance, indigenous uprisings, and the evolving roles of women, we gain a deeper understanding of the dynamic forces at play in Peru's quest for autonomy and self-determination.

[5] In the 18th century, amidst early attempts for independence from Spanish colonial rule in Peru, women faced the challenge of assuming leadership roles within their households due to the absence or flight of their husbands.

As indigenous uprisings and rebellions against colonial authority erupted, women found themselves navigating newfound autonomy and responsibilities, managing finances and familial affairs independently.

The Bourbon Reforms increased the unease, and the dissent had its outbreak in the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II which was repressed, but the root cause of the discontent of the indigenous people remained dormant.

It is debated whether these movements should be considered as precedents of the emancipation that was led by chiefs (caudillos), Peruvian towns (pueblos), and other countries in the American continent.

After success of the royalist armies, Abascal annexed Upper Peru to the viceroyalty, which benefited the Lima merchants as trade from the silver-rich region was now directed to the Pacific.

[7] Peru eventually succumbed to patriot armies after the decisive continental campaigns of José de San Martín (1820–1823) and Simón Bolívar (1823–1825).

The campaign of Sucre in Upper Peru concluded in April 1825, and in November of the same year Mexico obtained the surrender of the Spanish bastion of San Juan de Ulúa in North America.

[9] This was evidently the start of unrest and uprising of the junta movements between the divided country which caused royalist officials to become more aware and cautious of Cuzco and the southern parts of Perú as a whole.

Between 1809 and 1814, arguably the timeframe of the major junta movements and protests, Cuzco and the southern provinces of Peru were administratively and politically unstable, as expected from a country whose government is going through a general crisis.

This time frame has been characterized by uncertainty and overall confusing after the implementation of the Junta Central and the Council of Regency, efforts made by the then newly monarch-less and overruling Spain.

The rebellion began in a confrontation between the Constitutional Cabildo and the Audiencia of Cuzco, made up of officeholders and Europeans, over the administration of the city and spread much more rapidly than any prior movement.

Criollo leaders appealed to retired brigadier Mateo Pumacahua, then in his 70s, who was curaca of Chinchero, and decades earlier had been instrumental in suppressing the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II.

The rebellion continued to move their efforts towards Lima and Upper Peru to inspire and spread attention to the public[10] and officials opposed to their beliefs.

This movement also made note of the uselessness of the position of viceroyalty as a whole, though specifically in Upper Peru where it was the center of Royalist reaction[11] Pumacahua joined the Criollo leaders in forming a junta on 3 August in Cuzco, which demanded the complete implementation of the liberal reforms of the Spanish Constitution of 1812.

Reinforced with the royalist regiments of Lima and Arequipa, and expeditionary elements from Europe, the Viceroy of Peru organised several expeditions against the Patriots in Chile, Bolivia and Argentina.

Meanwhile, Patriot forces, overwhelmed in their attempts to advance through Upper Peru, shifted their strategy under the leadership of José de San Martin.

Actual hostilities began with the Sierra Campaign, led by patriot General Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales beginning on 5 October 1820.

The new viceroy announced his departure from Lima on 5 June 1821, but ordered a garrison to resist the patriots in the Real Felipe Fortress, leading to the First siege of Callao.

Following the interview, General San Martin abandoned Peru for Valparaiso on 22 September 1822 and left the entire command of the Independence movement to Simon Bolivar.

Following the self exile of San Martin, and the constant military defeats under president José de la Riva Agüero, the congress decided to send a plea in 1823 for the help of Simón Bolívar.

[citation needed] After the war of independence, conflicts of interests that faced different sectors of the Criollo society and the particular ambitions of individual caudillos, made the organization of the country excessively difficult.

Only three civilians: Manuel Pardo, Nicolás de Piérola and Francisco García Calderón would accede to the presidency in the first seventy-five years of independent life.