American Indian boarding schools

Similarly to schools that taught speakers of immigrant languages, the curriculum was rooted in linguistic imperialism, the English only movement, and forced assimilation enforced by corporal punishment.

He said the purpose of the mission, as an interpreter told the chief of a Native American tribe there, was "to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven".

The same records report that in 1677, "a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of Maryland, directed by two of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, made good progress.

So that not gold, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth alone, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher state of virtue and cultivation.

Religious missionaries from various denominations developed the first schools as part of their missions near indigenous settlements, believing they could extend education and Christianity to Native Americans.

The Foreign Mission School, a Protestant-backed institution that opened in Cornwall, Connecticut, in 1816, was set up for male students from a variety of non-Christian peoples, mostly abroad.

With the goal of assimilation, believed necessary so that tribal Indians could survive to become part of American society, the government increased its efforts to provide education opportunities.

While he required changes: the men had to cut their hair and wear common uniforms rather than their traditional clothes, he also granted them increased autonomy and the ability to govern themselves within the prison.

[27] Boarding schools were also established on reservations, where they were often operated by religious missions or institutes, which were generally independent of the local diocese, in the case of Catholic orders.

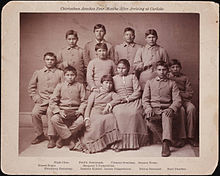

They were given short haircuts (a source of shame for boys of many tribes, who considered long hair part of their maturing identity), required to wear uniforms, and to take English names for use at the school.

They suffered physical, sexual, cultural and spiritual abuse and neglect, and experienced treatment that in many cases constituted torture for speaking their Native languages.

It generally forbade expenditures for separate education of children less than 1/4 Indian whose parents are citizens of the United States when they live in an area where adequate free public schools are provided.

[34] In 1926, the Department of the Interior (DOI) commissioned the Brookings Institution to conduct a survey of the overall conditions of American Indians and to assess federal programs and policies.

[34] The major spokesperson for the resolution Senator Arthur Watkins (Utah), stated: "As rapidly as possible, we should end the status of Indians as wards of the government and grant them all the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship"[34] The federal government implemented another new policy, aimed at relocating Indian people to urban cities and away from the reservations, terminating the tribes as separate entities.

[34] Given the lack of public sanitation and the often crowded conditions at boarding schools in the early 20th century, students were at risk for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, and trachoma.

And not least, apathetic boarding school officials frequently failed to heed their own directions calling for the segregation of children in poor health from the rest of the student body".

"[39] The 1928 Meriam Report noted that infectious disease was often widespread at the schools due to malnutrition, overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and students weakened by overwork.

Assimilation efforts included forcibly removing Native Americans from their families, converting them to Christianity, preventing them from learning or practicing indigenous culture and customs, and living in a strict military fashion.

Given the constraints of rural locations and limited budgets, boarding schools often operated supporting farms, raising livestock and produced their vegetables and fruit.

[44]: 11 School administrators argued that young women needed to be specifically targeted due to their important place in continuing assimilation education in their future homes.

[42]: 282 Removal to reservations in the West in the early part of the century and the enactment of the Dawes Act in 1887 eventually took nearly 50 million acres of land from Indian control.

Archuleta et al. (2000) noted cases where students had "their mouths washed out with lye soap when they spoke their native languages; they could be locked up in the guardhouse with only bread and water for other rule violations; and they faced corporal punishment and other rigid discipline on a daily basis".

The sustained terror in our hearts further tested our endurance, as it was better to suffer with a full bladder and be safe than to walk through the dark, seemingly endless hallway to the bathroom.

[45] Historian Brenda Child asserts that boarding schools cultivated pan-Indianism and made possible cross-tribal coalitions that helped many different tribes collaborate in the later 20th century.

Graduates of government schools often married former classmates, found employment in the Indian Service, migrated to urban areas, returned to their reservations and entered tribal politics.

Many students who returned to their reservations experienced alienation, language and cultural barriers, and confusion, in addition to post-traumatic stress disorder and the legacy of trauma from abuse.

[49] As mentioned by historians Brian Klopotek and Brenda Child, "A remote Indian population living in Northern Minnesota who, in 1900, took a radical position against the construction of a government school."

Speaking their language symbolized a bond that strictly attached them closer still to their culture, though it resulted in physical abuse which was feared; resistance continued in this form in order to cause frustration.

[52] When faculty visited former students, they rated their success based on the following criteria: "orderly households, 'citizen's dress', Christian weddings, 'well-kept' babies, land in severalty, children in school, industrious work habits, and leadership roles in promoting the same 'civilized' lifestyles among family and tribe".

Damning evidence related to years of abuses of students in off-reservation boarding schools contributed to the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act.