Indian rupee

While Shankar Goyal mentions it is unclear whether Panini was referring to coinage,[10] other scholars conclude that Panini uses the term rūpa to mean a piece of precious metal (typically silver) used as a coin, and a rūpya to mean a stamped piece of metal, a coin in the modern sense.

[12] The immediate precursor of the rupee is the rūpiya—the silver coin weighing 178 grains minted in northern India, first by Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule between 1540 and 1545, and later adopted and standardized by the Mughal Empire.

[16] The Gupta Empire produced large numbers of silver coins clearly influenced by those of the earlier Western Satraps by Chandragupta II.

[19] During his five-year rule from 1540 to 1545, Sultan Sher Shah Suri issued a coin of silver, weighing 178 grains (or 11.53 grams), which was also termed the rupiya.

In Britain War, the Long Depression resulted in bankruptcies, escalating unemployment, a halt in public works, and a major trade slump that lasted until 1897.

[29] They collected a wide range of testimony, examined as many as forty-nine witnesses, and only reported their conclusions in July 1899, after more than a year's deliberation.

[24] The prophecy made before the Committee of 1898 by Mr. A. M. Lindsay, in proposing a scheme closely similar in principle to that which was eventually adopted, has been largely fulfilled.

[30] The committee concurred in the opinion of the Indian government that the mints should remain closed to the unrestricted coinage of silver and that a gold standard should be adopted without delay...they recommended (1) that the British sovereign be given full legal tender power in India, and (2) that the Indian mints be thrown open to its unrestricted coinage (for gold coins only).These recommendations were acceptable to both governments and were shortly afterwards translated into laws.

It remained low until 1925, when the then Chancellor of the Exchequer (finance minister) of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, restored it to pre-war levels.

In the following year, both the quantity and the price rose further: net exports totalled 8.4 million ounces, valued at INR 65.52 crore.

[33] In the autumn of 1917 (when the silver price rose to 55 pence), there was danger of uprisings in India (against paper currency) which would handicap seriously British participation in the war.

It would prevent the further expansion of (paper currency) note issues and cause a rise of prices, in paper currency, that would greatly increase the cost of obtaining war supplies for export; to have reduced the silver content of this historic [rupee] coin might well have caused such popular distrust of the Government as to have precipitated an internal crisis, which would have been fatal to British success in the war.

As its designer explained, it was derived from the combination of the Devanagari consonant "र" (ra) and the Latin capital letter "R" without its vertical bar.

[37] The parallel lines at the top (with white space between them) are said to make an allusion to the flag of India,[38] and also depict an equality sign that symbolises the nation's desire to reduce economic disparity.

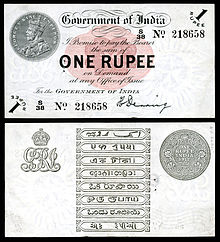

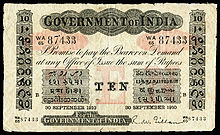

British East India Company (EIC) was given the right in 1717 to mint coins in the name of the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar on the island of Bombay.

After EIC expanded its control over India, it brought the "Coinage Act of 1835" and started to mint coins in the name of the British king.

[56] Commemorative coins of ₹125 were released on 4 September 2015 and 6 December 2015 to honour the 125th anniversary of the births of Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and B. R. Ambedkar, respectively.

The last of the regal issues were cupro-nickel 1⁄4-, 1⁄2- and one-rupee pieces minted in 1946 and 1947, bearing the image of George VI, King and Emperor on the obverse and an Indian lion on the reverse.

On 8 November 2016, the Government of India announced the demonetisation of ₹500 and ₹1,000 banknotes[68][69] with effect from midnight of the same day, making these notes invalid.

The next one (which is printed only in 10 and 50 denominations) is placed on the outer surface of the right temple of Gandhi's spectacles near his ear and reads "RBI" (Reserve Bank of India) and the face value in numerals "10" or "50".

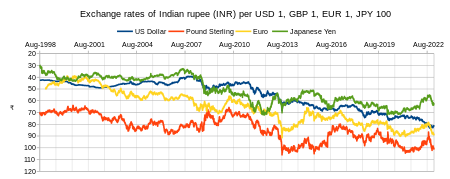

However, the Reserve Bank of India trades actively in the USD/INR currency market to impact effective exchange rates.

Thus, the currency regime in place for the Indian rupee with respect to the US dollar is a de facto controlled exchange rate.

[80] Unlike China, successive administrations (through RBI, the central bank) have not followed a policy of pegging the INR to a specific foreign currency at a particular exchange rate.

On the current account, there are no currency-conversion restrictions hindering buying or selling foreign exchange (although trade barriers exist).

On the capital account, foreign institutional investors have concerning convertibility to bring money into and out of the country and buy securities (subject to quantitative restrictions).

To meet the Home Charges (i.e., expenditure in the United Kingdom), the colonial government had to remit a larger number of rupees, and this necessitated increased taxation, unrest and nationalism.

[96] Five years later, when the Bretton Woods system was suspended, India initially announced that it will maintain a fixed rate of $1 to INR 7.50 and leave the sterling under a floating regime.

[97] However, by the end of 1971, following the Smithsonian Agreement and the subsequent devaluation of the US dollar, India pegged the rupee with the pound sterling once again at a rate of £1 to INR 18.9677.

Previously the Indian rupee was an official currency of other countries, including Aden, Oman, Dubai, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the Trucial States, Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, the Seychelles and Mauritius.

The Nepalese rupee is pegged at ₹0.625; the Indian rupee is accepted in Bhutan and Nepal, except ₹500 and ₹1000 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi Series and the ₹200, ₹500 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi New Series, which are not legal tender in Bhutan and Nepal and are banned by their respective governments, though accepted by many retailers.