Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent

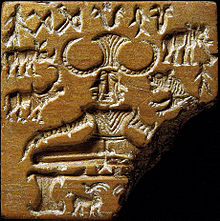

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley Civilization, and a more widespread tradition of small terracotta figures, mostly either of women or animals, which predates it.

[1] After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of larger sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.

[3] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood that also embraced Hinduism.

[11] It has been suggested that the early Vedic religion focused exclusively on the worship of purely "elementary forces of nature by means of elaborate sacrifices", which did not lend themselves easily to anthropomorphological representations.

The most significant remains of monumental Mauryan art include the remains of the royal palace and the city of Pataliputra, a monolithic rail at Sarnath, the Bodhimandala or the altar resting on four pillars at Bodhgaya, the rock-cut chaitya-halls in the Barabar Caves near Gaya, the non-edict bearing and edict bearing pillars, the animal sculptures crowning the pillars with animal and botanical reliefs decorating the abaci of the capitals and the front half of the representation of an elephant carved out in the round from a live rock at Dhauli.

Stone sculpture was much later to arrive in South India than the north, and the earliest period is only represented by the Gudimallam Lingam with a standing figure of Shiva, from the southern tip of Andhra Pradesh.

The "mysteriousness" of this "lies in the total absence so far of any object in an even remotely similar manner within many hundreds of miles, and indeed anywhere in South India".

[21] The form of the Gudimallam Lingam, for example, would be a natural one to evolve in wood, using a straight tree trunk very efficiently, but to say that it did so is pure speculation in our present state of knowledge.

Wooden sculpture, and architecture, has remained common in Kerala, where stone is hard to come by, but this means survivals are very largely limited to the last few centuries.

Some aspects of Greek art were adopted while others did not spread beyond the Greco-Buddhist area; in particular the standing figure, often with a relaxed pose and one leg flexed, and the flying cupids or victories, who became popular across Asia as apsaras.

[27] Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human form before this time, but only through some of his symbols.

Artistically, the Gandharan school of sculpture is said to have contributed wavy hair, drapery covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, acanthus leaf decorations, etc.

The Gupta period is generally regarded as a classic peak and golden age of North Indian art for all the major religious groups.

The period saw the emergence of the iconic carved stone deity in Hindu art, while the production of the Buddha-figure and Jain tirthankara figures continued to expand, the latter often on a very large scale.

Minor figures such as yakshi, which had been very prominent in preceding periods, are now smaller and less frequently represented, and the crowded scenes illustrating Jataka tales of the Buddha's previous lives are rare.

Buddhist, Hindu and Jain sculpture all show the same style,[41] and there is a "growing likeness of form" between figures from the different religions, which continued after the Gupta period.

[42] The detail of facial parts, hair, headgear, jewellery and the haloes behind figures are carved very precisely, giving a pleasing contrast with the emphasis on broad swelling masses in the body.

[43] Deities of all the religions are shown in a calm and majestic meditative style; "perhaps it is this all-pervading inwardness that accounts for the unequalled Gupta and post-Gupta ability to communicate higher spiritual states".

[44] Though the Pala monarchs are recorded as patronizing religious establishments in a general sense, their patronage of any specific work of art cannot be documented by the surviving evidence, which is mostly inscriptions.

[45] However, there are much larger numbers of images that are dated, as compared to other Indian regions and periods, helping greatly the reconstruction of stylistic development.

Gradually, Hindu figures come to outnumber Buddhist ones, reflecting the terminal decline of Indian Buddhism, even in east India, its last stronghold.

The sculptures depict various aspects the everyday life, mythical stories as well as symbolic display of various secular and spiritual values important in Hindu tradition.

Initially these tend to be rock-cut, as are most of the Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram (7th and 8th centuries), perhaps the best-known examples of Pallava art and architecture Many of these exploit natural outcrops of rock, which are carved away on all sides until a building is left.

The Descent of the Ganges at Mahabalipuram, is "the largest and most elaborate sculptural composition in India",[49] a relief carved on a near-vertical rock face some 29 metres (86 feet) wide, featuring hundreds of figures, including a life-size elephant (late 7th century).

In large narrative panels some of the subjects are distinctively Tamil, such as Korravai (Durga as goddess of victory), and Somaskanda, a seated family group of Shiva, his consort Parvati and Skanda (Murugan) as a child.

Chola bronzes, the largest mostly about half life-size, are some of the most iconic and famous sculptures of India, using a similar elegant but powerful style to the stone pieces.

By the end of the period hugely expanded multi-storey gopurams had become the most prominent feature of templeas, as they have remained in the major temples of the south.

Modern Indian sculptors include D.P Roy Choudhury, Ramkinkar Baij, Pilloo Pochkhanawala, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Adi Davierwala, Sankho Chaudhuri and Chintamoni Kar.