Traditional knowledge

These systems of knowledge are generally based on accumulations of empirical observation of and interaction with the environment, transmitted orally across generations.

[2][3] The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the United Nations (UN) include traditional cultural expressions (TCE) in their respective definitions of indigenous knowledge.

These sophisticated sets of understandings, interpretations and meanings are part and parcel of a cultural complex that encompasses language, naming and classification systems, resource use practices, ritual, spirituality and worldview.

Chamberlin (2003) writes of a Gitksan elder from British Columbia confronted by a government land-claim: "If this is your land," he asked, "where are your stories?

Critics of traditional knowledge, however, see such demands for "respect" as an attempt to prevent unsubstantiated beliefs from being subjected to the same scrutiny as other knowledge-claims.

[citation needed] This has particular significance for environmental management because the spiritual component of "traditional knowledge" can justify any activity, including the unsustainable harvesting of resources.

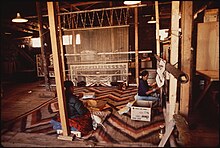

They are transmitted from one generation to the next, and include handmade textiles, paintings, stories, legends, ceremonies, music, songs, rhythms and dance.

[16] During the committee's sessions, representatives of indigenous and local communities host panels relating to the preservation of traditional knowledge.

Truth is considered relativist, and relies on what is meant or understood, which is not always translatable between individuals or cultures owing to differing paradigms and linguistical conventions.

Universal justifiers of epistemological claims are: linguistic-conceptual schemes, human nature, socio-cultural values and interests, and customs and habits, which commonly instil confidence.

In 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognized the value of traditional knowledge in protecting species, ecosystems and landscapes, and incorporated language regulating access to it and its use (discussed below).

), WIPO established the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC-GRTKF).

The high-level Brundtland Report (1987) recommended a change in development policy that allowed for direct community participation and respected local rights and aspirations.

The Rio Declaration (1992), endorsed by the presidents and ministers of the majority of the countries of the world, recognized indigenous and local communities as distinct groups with special concerns that should be addressed by states.

Indigenous peoples and local communities have sought to prevent the patenting of traditional knowledge and resources where they have not given express consent.

Some have been willing to investigate how existing intellectual property mechanisms (primarily: patents, copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets) can protect traditional knowledge.

On this point the Tulalip Tribes of Washington state has commented that "open sharing does not automatically confer a right to use the knowledge (of indigenous people)... traditional cultural expressions are not in the public domain because indigenous peoples have failed to take the steps necessary to protect the knowledge in the Western intellectual property system, but from a failure of governments and citizens to recognise and respect the customary laws regulating their use".

[23] Equally, however, the idea of restricting the use of publicly available information without clear notice and justification is regarded by many in developed nations as unethical as well as impractical.

Nevertheless, the provisions regarding Access and Benefit Sharing contained in the Convention on Biological Diversity never achieved consensus and soon the authority over these questions fell back to WIPO.

Key players, such as local communities and indigenous peoples, should be recognized by States, and have their sovereignty recognised over the biodiversity of their territories, so that they can continue protecting it.

[32] The parties to the Convention set a 2010 target to negotiate an international legally binding regime on access and benefit sharing (ABS) at the Eighth meeting (COP8), 20–31 March 2006 in Curitiba, Brazil.

[34] In 2001, the Government of India set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) as repository of 1200 formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as Ayurveda, Unani and Siddha and 1500 Yoga postures (asanas), translated into five languages – English, German, French, Spanish and Japanese.

The Intellectual Property Rights Policy for Kerala released in 2008[35] proposes adoption of the concepts 'knowledge commons' and 'commons licence' for the protection of traditional knowledge.

[3] Proponents also argue that its inclusion combats disillusionment among indigenous groups with the education system and helps to preserve their cultural identity.

[40][41] Studies indicate that if the introduction of TK into educational curriculums is to succeed, it would need to taught from the perspective of the relevant worldview, involve community participation, and have a bridge built between the national/dominant language and the indigenous one.

[41] Efforts to include it in education have been criticized on the grounds that it is inseparable from spiritual and religious beliefs; that it is not possible to reconcile contradictions between science and TK; that time spent on it comes at the cost of time delivering curricula that meets international academic standards; that policies granting science and indigenous knowledge equal status are based on relativism and inhibit science from questioning claims made by indigenous knowledge systems; and that many proponents of indigenous knowledge engage in ideological antiscience rhetoric.

[41] In New Zealand, an indigenous vitalist concept (mauri) was introduced into the national chemistry curriculum citing an 'equal status' policy, amid objections from science teachers.