Indigenous peoples in Chile

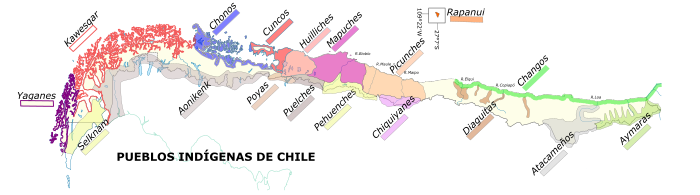

There are also small populations of Aymara, Quechua, Atacameño, Qulla (Kolla), Diaguita, Yahgan (Yámana), Rapa Nui and Kawésqar (Alacalufe) people in other parts of the country,[3] as well as many other groups such as Caucahue, Chango, Picunche, Chono, Tehuelche, Cunco and Selk'nam (Ona).Before the Spanish arrived in the mid 16th century, Chile was home to the southernmost portion of the Inca Empire.

Instead they chose to side with the Spanish, because the imperial power’s legal recognition of the Mapuche tribe made them more of a known quantity than the Chilean rebels.

President Patricio Aylwin Azócar’s Concertación government established a Comisión Especial de Pueblos indígenas (Special Commission of Indigenous People).

[3] Part of that cultural recognition included legalizing the Mapudungun language and providing a bilingual education in schools with indigenous populations.

The Indigenous Law recognized in particular the Mapuche people, victims of the Occupation of the Araucanía from 1861 to 1883, as an inherent part of the Chilean nation.

Other indigenous people officially recognized included Aymara, Atacameña, Colla, Quechua, Rapa-Nui (Polynesian inhabitants of Easter Island), Yahgan (Yámana), Kawésqar, Diaguita (since 2006), Chango (since 2020) and Selk'nam (Ona) (since 2023).

In November 2009, a court decision in Chile, considered to be a landmark in indigenous rights concerns, made use of the ILO convention 169.

[10] Despite the benefits established by Indigenous Law, it still has its limitations, spurring the emergence of organized Mapuche movements for more direct constitutional recognition.

Recognition of plurinational status in Chile would enshrine the indigenous population as its own group deserving of political representation, autonomy, and territorial protection.

The rejected constitutional proposals would have safeguarded environmental protections, established gender parity, and extended access to education for the Mapuche people, among a host of other social and democratic provisions.

[12] The lack of reform is a result of the deep rooted inequality within the Chilean government, stemming from Pinochet-era policies that favor urban elites over environmental and indigenous issues.

[3] The Ministry of Education provided a package of financial aid consisting of 1,200 scholarships for indigenous elementary and high school students in the Araucania Region during 2005.

[20] Their lack of political influence is evident in their interactions with businesses such as Forestry Farms and Lumber companies that exploit Indigenous land.

Since 2009, there have been frequent instances of violent confrontations between indigenous Mapuche groups and landowners, logging companies, and local government authorities in the southern part of the country.

[3] The government did not act on a United Nations special rapporteur's 2003 recommendation that there be a judicial review of cases affecting Mapuche leaders.

Citing past rhetoric associated with CAM’s political demands, media and business sectors painted a violent picture of the Mapuche community members allegedly involved.

[24] The incident exposed repeated patterns of violent associations cast on Mapuche activist groups by the press (See also: Rapa Nui police repression and Aymara mining protests).

Both groups have expressed a willingness to use violence, attacking and sabotaging forestry operations, infrastructural corporations, and private homes of non-indigenous civilians who live on former indigenous lands.

[26] Chile has attempted to develop hydropower projects in indigenous territory where the rivers that the energy companies hope to use are sacred to the Mapuche people.

One area impacted by hydropower development is the Puelwillimapu Territory, whose interconnected waterways are referred to as the watershed of Wenuleufu or the ‘River Above,’ giving the region spiritual value.

[27] The government protects these areas as a means of supporting ecological development while also ensuring that indigenous groups are able to maintain control of culturally significant locations.

Recent studies have found that Indigenous people were much more likely to die from COVID-19 related deaths and were much more susceptible to the virus than any other group in Chile.