Indo-Iranians

[17][18] Population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, in his 1994 book The History and Geography of Human Genes, also uses the term Aryan to describe the Indo-Iranians.

[25] Historical linguists broadly estimate that a continuum of Indo-Iranian languages probably began to diverge by 2000 BC,[26]: 38–39 preceding both the Vedic and Iranian cultures which emerged later.

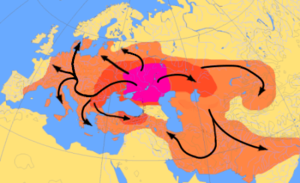

It is assumed that this expansion spread from the Proto-Indo-European homeland north of the Caspian Sea south to the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Iranian plateau, and the Indian subcontinent.

The Mitanni, a people known in eastern Anatolia from about 1500 BC, were of possibly of mixed origins: An indigenous non Indo-European Hurrian-speaking majority was supposedly dominated by a non-Anatolian, Indo-Aryan elite.

[citation needed] The standard model for the entry of the Indo-European languages into the Indian subcontinent is that this first wave went over the Hindu Kush, either into the headwaters of the Indus and later the Ganges.

The Indo-Aryans in these areas established several powerful kingdoms and principalities in the region, from south eastern Afghanistan to the doorstep of Bengal.

Today, Indo-Aryan languages are spoken in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Fiji, Suriname and the Maldives.

The populous Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, dwelling near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia in the Achaemenid Period.

At their greatest reported extent, around 1st century AD, the Sarmatian tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian seas as well as the Caucasus to the south.

The regions where Indo-Iranian languages are spoken extend from Europe (Romani) and the Caucasus (Ossetian, Tat and Talysh), down to Mesopotamia (Kurdish languages, Zaza–Gorani and Kurmanji Dialect continuum[36]) and Iran (Persian), eastward to Xinjiang (Sarikoli) and Assam (Assamese), and south to Sri Lanka (Sinhala) and the Maldives (Maldivian), with branches stretching as far out as Oceania and the Caribbean for Fiji Hindi and Caribbean Hindustani respectively.

[47] Similarly, in early portions of the Avesta, Iranian *Harahvati is the world-river that flows down from the mythical central Mount Hara.

Both collections are from the period after the proposed date of separation (c. 2nd millennium BC) of the Proto-Indo-Iranians into their respective Indic and Iranian branches.

[58] Data so far collected indicates high frequency of R-Z93 in the northern Indian Subcontinent, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan: Bengali Brahmins carry up to 72% R1a1a,[59] Mohana tribe up to 71%,[60] Nepal Hindus up to 69.20%,[61] and Tajiks up to 68%.

[62] The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during the Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian maternal lineages (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th century BC, all Kazakh samples belonged to European lineages.

[63] A 2022 study found that modern individuals from Southern Central Asia, especially Tajiks and Yaghnobis, display strong genetic continuity towards Iron Age Indo-Iranians, and were only marginally affected by outside geneflow, while modern Turkic peoples derive significant amounts of ancestry from a 'Baikal hunter-gatherer' source (mean average ~50%), with the remainder being ancestry maximized in Tajik people.