Pesticide resistance

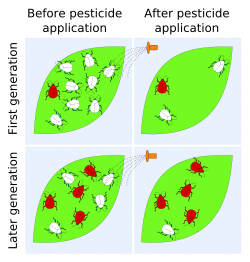

The Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) definition of insecticide resistance is 'a heritable change in the sensitivity of a pest population that is reflected in the repeated failure of a product to achieve the expected level of control when used according to the label recommendation for that pest species'.

For example, the northern corn rootworm (Diabrotica barberi) became adapted to a corn-soybean crop rotation by spending the year when the field is planted with soybeans in a diapause.

With the introduction of every new insecticide class – cyclodienes, carbamates, formamidines, organophosphates, pyrethroids, even Bacillus thuringiensis – cases of resistance surfaced within two to 20 years.

Insecticides are widely used across the world to increase agricultural productivity and quality in vegetables and grains (and to a lesser degree the use for vector control for livestock).

For example, some Anopheles mosquitoes evolved a preference for resting outside that kept them away from pesticide sprayed on interior walls.

Scientists have researched ways to use this enzyme to break down pesticides in the environment, which would detoxify them and prevent harmful environmental effects.

A similar enzyme produced by soil bacteria that also breaks down organochlorides works faster and remains stable in a variety of conditions.

[30] Resistance to gene drive forms of population control is expected to occur and methods of slowing its development are being studied.

Guerrero et al. 1997 used the newest methods of the time to find mutations producing pyrethroid resistance in dipterans.

A complementary approach is to site untreated refuges near treated croplands where susceptible pests can survive.

This involves switching among pesticide classes with different modes of action to delay or mitigate pest resistance.

[47] Two or more pesticides with different modes of action can be tankmixed on the farm to improve results and delay or mitigate existing pest resistance.

[38] Glyphosate-resistant weeds are now present in the vast majority of soybean, cotton, and corn farms in some U.S. states.

Weed surveys from some 500 sites throughout Iowa in 2011 and 2012 revealed glyphosate resistance in approximately 64% of waterhemp samples.

[7] In response to the rise in glyphosate resistance, farmers turned to other herbicides—applying several in a single season.

In the United States, most midwestern and southern farmers continue to use glyphosate because it still controls most weed species, applying other herbicides, known as residuals, to deal with resistance.

Multiple studies have found the practice to be either ineffective or to accelerate the development of resistant strains.