Insulin shock therapy

In 1927, Sakel, who had recently qualified as a medical doctor in Vienna and was working in a psychiatric clinic in Berlin, began to use low (sub-coma) doses of insulin to treat drug addicts and psychopaths, and when one of the patients experienced improved mental clarity after having slipped into an accidental coma, Sakel reasoned the treatment might work for mentally ill patients.

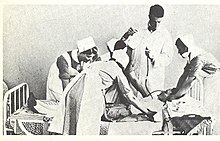

[3] Having returned to Vienna, he treated schizophrenic patients with larger doses of insulin in order to deliberately produce coma and sometimes convulsions.

[2] Patients, who were almost invariably diagnosed with schizophrenia, were selected on the basis of having a good prognosis and the physical strength to withstand an arduous treatment.

[7] After about 50 or 60 comas, or earlier if the psychiatrist thought that maximum benefit had been achieved, the dose of insulin was rapidly reduced before treatment was stopped.

[8] After the insulin injection patients would experience various symptoms of decreased blood glucose: flushing, pallor, perspiration, salivation, drowsiness or restlessness.

These observations led the Hungarian neuropsychiatrist Ladislas Meduna to induce seizures in schizophrenic patients with injections of camphor, soon replaced by pentylenetetrazol (Metrazole).

[14] The hypoglycemia (pathologically low glucose levels) that resulted from insulin coma therapy made patients extremely restless, sweaty, and liable to further convulsions and "after-shocks".

In addition, patients invariably emerged from the long course of treatment "grossly obese",[5] probably due to glucose rescue-induced glycogen storage disease.

[16] Respected singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt was said to have lost much of his long-term memory from this treatment, performed on him for bipolar disorder, preceding a life of substance abuse and depression.

The numbers of patients were restricted by the requirement for intensive medical and nursing supervision and the length of time it took to complete a course of treatment.

[22] The results were essentially the same in relief and discharge ratings but chlorpromazine was safer with fewer side-effects, easier to administer, and better suited to long-term care.

[citation needed] In 1958, Bourne published a paper on increasing disillusionment in the psychiatric literature about insulin coma therapy for schizophrenia.

He suggested there were several reasons it had received almost universal uncritical acceptance by reviews and textbooks for several decades despite the occasional disquieting negative finding, including that, by the 1930s when it all started, schizophrenics were considered inherently unable to engage in psychotherapy, and insulin coma therapy "provided a personal approach to the schizophrenic, suitably disguised as a physical treatment so as to slip past the prejudices of the age.

In the US, Deborah Doroshow wrote that insulin coma therapy secured its foothold in psychiatry not because of scientific evidence or knowledge of any mechanism of therapeutic action, but due to the impressions it made on the minds of the medical practitioners within the local world in which it was administered and the dramatic recoveries observed in some patients.

[5] Doroshow argues that "psychiatrists used complications to exert their practical and intellectual expertise in a hospital setting" and that collective risk-taking established "especially tight bonds among unit staff members".

[14] Leonard Roy Frank, an American activist from the psychiatric survivors movement who underwent 50 forced insulin coma treatments combined with ECT, described the treatment as "the most devastating, painful and humiliating experience of my life", a "flat-out atrocity" glossed over by psychiatric euphemism, and a violation of basic human rights.

[30] Like many new medical treatments for diseases previously considered incurable, depictions of insulin coma therapy in the media were initially favorable.

In Kelly Rimmer's book, The German Wife, the character Henry Davis undergoes insulin shock therapy to treat 'combat fatigue'.