Intercept theorem

It is equivalent to the theorem about ratios in similar triangles.

It is traditionally attributed to Greek mathematician Thales.

It was known to the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians, although its first known proof appears in Euclid's Elements.

Let A, B be the intersections of the first ray with the two parallels, such that B is further away from S than A, and similarly C, D are the intersections of the second ray with the two parallels such that D is further away from S than C. In this configuration the following statements hold:[1][2] The first two statements remain true if the two rays get replaced by two lines intersecting in

is not located between the two parallels, the original theorem applies directly.

yields V figure with identical measures for which the original theorem now applies.

[2] The third statement (converse) however does not remain true for lines instead of rays.

[3][4][5] However, if one replaces ratio of lengths with signed ratios of directed line segments, all statements of the intercept theorem including the converse remain valid for lines as well.

[4] An homothety of positive ratio k with center O maps a point A to the point B located on the ray OA such that The converse of the theorem implies that a homothety transforms a line in a parallel line.

The intercept theorem is closely related to similarity.

By matching identical angles you can always place two similar triangles in one another so that you get the configuration in which the intercept theorem applies; and conversely the intercept theorem configuration always contains two similar triangles.

In a normed vector space, the axioms concerning the scalar multiplication (in particular

There are three famous problems in elementary geometry which were posed by the Greeks in terms of compass and straightedge constructions:[6][7] It took more than 2000 years until all three of them were finally shown to be impossible.

In order to reformulate the three problems in algebraic terms using field extensions, one needs to match field operations with compass and straightedge constructions (see constructible number).

In particular it is important to assure that for two given line segments, a new line segment can be constructed, such that its length equals the product of lengths of the other two.

Similarly one needs to be able to construct, for a line segment of length

The intercept theorem can be used to show that for both cases, that such a construction is possible.

The following graphic shows the partition of a line segment

[8] According to some historical sources the Greek mathematician Thales applied the intercept theorem to determine the height of the Cheops' pyramid.

The following description illustrates the use of the intercept theorem to compute the height of the pyramid.

It does not, however, recount Thales' original work, which was lost.

[9][10] Thales measured the length of the pyramid's base and the height of his pole.

This yielded the following data: From this he computed Knowing A, B and C he was now able to apply the intercept theorem to compute The intercept theorem can be used to determine a distance that cannot be measured directly, such as the width of a river or a lake, the height of tall buildings or similar.

The graphic to the right illustrates measuring the width of a river.

The intercept theorem can be used to prove that a certain construction yields parallel line (segment)s. If the midpoints of two triangle sides are connected then the resulting line segment is parallel to the third triangle side (Midpoint theorem of triangles).

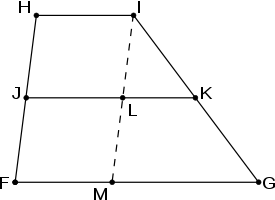

If the midpoints of the two non-parallel sides of a trapezoid are connected, then the resulting line segment is parallel to the other two sides of the trapezoid.

The theorem is traditionally attributed to the Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus, who may have used some form of the theorem to determine heights of pyramids in Egypt and to compute the distance of ship from the shore.

[11][12][13][14] An elementary proof of the theorem uses triangles of equal area to derive the basic statements about the ratios (claim 1).

) denote its area and for a line segment its length.

As those triangles share the same baseline, their areas are identical.