Interference theory

[1] Retaining information regarding the relevant time of encoding memories into LTM influences interference strength.

His experiment was similar to the Stroop task and required subjects to sort two decks of cards with words into two piles.

[2] German psychologists continued in the field with Georg Elias Müller and Pilzecker in 1900 studying retroactive interference.

[8] Delos Wickens discovered that proactive interference build-up is released when there is a change to the category of items being learned, leading to increased processing in STM.

[9] Presenting new skills later in practice can considerably reduce proactive interference desirable for participants to have the best opportunity to encode fresh new memories into LTM.

[clarification needed][15][16] With single tasks, proactive interference had less effect on participants with high working memory spans than those with low ones.

Turvey and Wittlinger designed an experiment to examine the effects of cues such as "not to remember" and "not to recall" with currently learned material.

Therefore, these associated cues do not directly control the potential effect of proactive interference on short-term memory span.

[clarification needed][17] Proactive interference has shown an effect during the learning phase in terms of stimuli at the acquisition and retrieval stages with behavioral tasks for humans, as found by Castro, Ortega, and Matute.

The research, as predicted, showed retardation and impairment in associations, due to the effect of Proactive Interference.

The effect of retroactive interference takes place when any type of skill has not been rehearsed over long periods.

[19] These memory research pioneers demonstrated that filling the retention interval (defined as the amount of time that occurs between the initial learning stage and the memory recall stage) with tasks and material caused significant interference effects with the primary learned items.

A significant part of Briggs's (1954) study was that once participants were tested after a delay of 24 hours the Bi responses spontaneously recovered and exceeded the recall of the Ci items.

The main difference in this study, however, was that, unlike Briggs's (1954) "modified free recall" (MFR) task where participants gave one-item responses, Barnes and Underwood asked participants to give both List 1 and List 2 responses to each cued recall task.

[1] Afterwards, forgetting diminishes at a gradual rate, which leaves about 5% to 10% of retained information available for learners to access from practice until the next session.

The important conclusion one may gain from RI is that "forgetting is not simply a failure or weakness of the memory system" (Bjork, 1992), but rather an integral part of our stored knowledge repertoire.

Although modern cognitive researchers continue to debate the actual causes of forgetting (e.g., competition vs. unlearning), retroactive interference implies a general understanding that additional underlying processes play a role in memory.

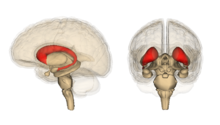

[23] The study found that adults 55–67 years of age showed less magnetic activity in their prefrontal cortices than the control group.

Executive control mechanisms are located in the frontal cortex and deficits in working memory show changes in the functioning of this brain area.

[24] The researcher found that the presentation of subsequent stimuli in succession causes a decrease in recalled accuracy.

[24] Wohldmann, Healey, and Bourne found that Retroactive Interference also affects the retention of motor movements.

[27] This finding contrasts the control condition as they had little Retroactive Inference when asked to recall the first-word list after a period of unrelated activity.

Henry L. Roediger III and Schmidt found that the act of retrieval can serve as the source of the failure to remember, using multiple experiments that tested the recall of categorized and paired associative lists.

A fourth experiment revealed that only recent items were present in output interference in paired associative lists.

The performance of Stroop and Simon tasks were monitored on 10 healthy young adults using magnetic resonance image (MRI) scanning.

[38] It has been demonstrated that recall will be lower when consumers have afterward seen an ad for a competing brand in the same product class.

Exposure to later similar advertisements does not cause interference for consumers when brands are rated on purchasing likelihood.

When competitive advertising was presented, it was shown that repetition provided no improvement in brand name recall over a single exposure.

Presenting ads in multi-modalities (visual, auditory) will reduce possible interference because there are more associations or paths to cue recall than if only one modality had been used.

Therefore, by presenting ads in multiple modalities, the chance that the target brand has unique cues is increased.