Internal model (motor control)

A. Francis and W. M. Wonham[1] as an explicit formulation of the Conant and Ashby good regulator theorem.

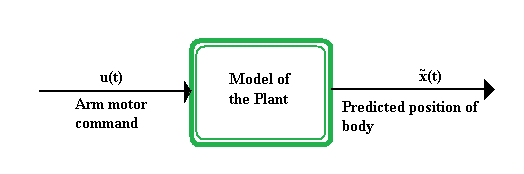

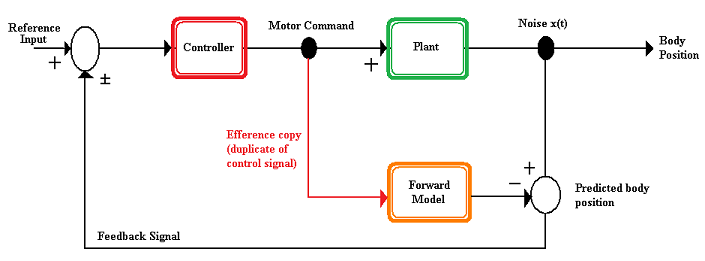

In their simplest form, forward models take the input of a motor command to the “plant” and output a predicted position of the body.

Michael I. Jordan, Emanuel Todorov and Daniel Wolpert contributed significantly to the mathematical formalization.

Sandro Mussa-Ivaldi, Mitsuo Kawato, Claude Ghez, Reza Shadmehr, Randy Flanagan and Konrad Kording contributed with numerous behavioral experiments.

Two interesting inverse internal models for the control of speech production[6] were developed by Iaroslav Blagouchine & Eric Moreau.

[7] Both models combine the optimum principles and the equilibrium-point hypothesis (motor commands λ are taken as coordinates of the internal space).

There is also a rich clinical literature on internal models including work from John Krakauer,[8] Pietro Mazzoni, Maurice A. Smith, Kurt Thoroughman, Joern Diedrichsen, and Amy Bastian.