Intraspecific competition

[2] Individuals can compete for food, water, space, light, mates, or any other resource which is required for survival or reproduction.

As a result, the growth rate of a population slows as intraspecific competition becomes more intense, making it a negatively density dependent process.

[3] Intraspecific competition does not just involve direct interactions between members of the same species (such as male deer locking horns when competing for mates) but can also include indirect interactions where an individual depletes a shared resource (such as a grizzly bear catching a salmon that can then no longer be eaten by bears at different points along a river).

As organisms are encountering each other during interference competition, they are able to evolve behavioural strategies and morphologies to out-compete rivals in their population.

[4] For example, different populations of the northern slimy salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) have evolved varying levels of aggression depending on the intensity of intraspecific competition.

It is a more effective strategy to fight rivals within the species harder instead of searching for other options due to the lack of available food.

Mates are a fiercely contested resource in many species as the production of offspring is essential for an individual to propagate its genes.

Exploitative competition involves individuals depleting a shared resource and both suffering a loss in fitness as a result.

This is also seen in Viviparous lizard, or Lacerta vivipara, where the existence of color morphs within a population depends on the density and intraspecific competition.

Like exploitative competition, the individuals aren’t interacting directly but rather suffer a reduction in fitness as a consequence of the increasing population size.

For example, native skinks (Oligosoma) in New Zealand suffered a large decline in population after the introduction of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus).

For instance: white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) have different energy intakes based on their ranking within the group.

As a result, many species have evolved forms of ritualised combat to determine who wins access to a resource without having to undertake a dangerous fight.

Male elephant seals, Mirounga augustirostris, engage in fierce competitive displays in an attempt to control a large harem of females with which to mate.

[13] The potential reproductive success for males is so great that many are killed before breeding age as they attempt to move up the hierarchy in their population.

The uneven distribution of resources results in some individuals dying off but helps to ensure that the members of the population that hold a territory can reproduce.

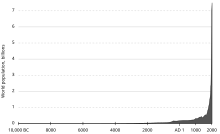

For instance, grazing animals compete more strongly for grass as their population grows and food becomes a limiting resource.

Elephant (Loxodonta africana) populations in Kruger National Park (South Africa) also grew exponentially in the mid-1900s after strict poaching controls were put in place.

dN(t)/dt = rate of change of population density N(t) = population size at time t r = per capita growth rate K = carrying capacity The logistic growth equation is an effective tool for modelling intraspecific competition despite its simplicity, and has been used to model many real biological systems.

However, as N(t) approaches the carrying capacity the second term in the logistic equation becomes smaller, reducing the rate of change of population density.

[17] The inflexion point in the Daphnia population density graph occurred at half the carrying capacity, as predicted by the logistic growth model.