Nicomachus

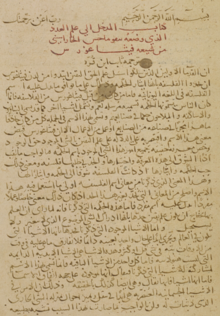

Nicomachus' work on arithmetic became a standard text for Neoplatonic education in Late antiquity, with philosophers such as Iamblichus and John Philoponus writing commentaries on it.

A Latin paraphrase by Boethius of Nicomachus's works on arithmetic and music became standard textbooks in medieval education.

[1] His Manual of Harmonics was addressed to a lady of noble birth, at whose request Nicomachus wrote the book, which suggests that he was a respected scholar of some status.

[2] He mentions his intent to write a more advanced work, and how the journeys he frequently undertakes leave him short of time.

[1] He mentions Thrasyllus in his Manual of Harmonics, and his Introduction to Arithmetic was apparently translated into Latin in the mid 2nd century by Apuleius,[2]while he makes no mention at all of either Theon of Smyrna's work on arithmetic or Ptolemy's work on music, implying that they were either later contemporaries or lived in the time after he did.

[6] Unlike many other Neopythagoreans, such as Moderatus of Gades, Nicomachus makes no attempt to distinguish between the Demiurge, who acts on the material world, and The One which serves as the supreme first principle.

[1] The Theology of Arithmetic (Ancient Greek: Θεολογούμενα ἀριθμητικῆς), on the Pythagorean mystical properties of numbers in two books is mentioned by Photius.

Introduction to Arithmetic (Ancient Greek: Ἀριθμητικὴ εἰσαγωγή, Arithmetike eisagoge) is the only extant work on mathematics by Nicomachus.

Nicomachus also describes how natural numbers and basic mathematical ideas are eternal and unchanging, and in an abstract realm.

Manuale Harmonicum (Ἐγχειρίδιον ἁρμονικῆς, Encheiridion Harmonikes) is the first important music theory treatise since the time of Aristoxenus and Euclid.

It provides the earliest surviving record of the legend of Pythagoras's epiphany outside of a smithy that pitch is determined by numeric ratios.

Nicomachus's discussion of the governance of the ear and voice in understanding music unites Aristoxenian and Pythagorean concerns, normally regarded as antitheses.

[10] In the midst of theoretical discussions, Nicomachus also describes the instruments of his time, also providing a valuable resource.

[12] The work of Boethius on arithmetic and music was a core part of the Quadrivium liberal arts and had a great diffusion during the Middle Ages.