Acid dissociation constant

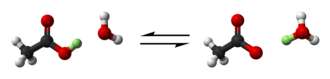

[a] The system is said to be in equilibrium when the concentrations of its components do not change over time, because both forward and backward reactions are occurring at the same rate.

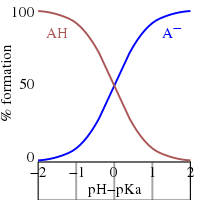

[1] The dissociation constant is defined by[b] where quantities in square brackets represent the molar concentrations of the species at equilibrium.

In living organisms, acid–base homeostasis and enzyme kinetics are dependent on the pKa values of the many acids and bases present in the cell and in the body.

In chemistry, a knowledge of pKa values is necessary for the preparation of buffer solutions and is also a prerequisite for a quantitative understanding of the interaction between acids or bases and metal ions to form complexes.

A broader definition of acid dissociation includes hydrolysis, in which protons are produced by the splitting of water molecules.

To avoid the complications involved in using activities, dissociation constants are determined, where possible, in a medium of high ionic strength, that is, under conditions in which

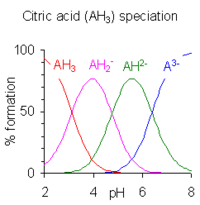

[28] For oxyacids with more than one ionizable hydrogen on the same atom, the pKa values often increase by about 5 units for each proton removed,[29][30] as in the example of phosphoric acid above.

Substitute the expression for [AH] from the second equation into the first equation At the isoelectric point the concentration of the positively charged species, AH+2, is equal to the concentration of the negatively charged species, A−, so Therefore, taking cologarithms, the pH is given by pI values for amino acids are listed at proteinogenic amino acid.

In water, the concentration of the hydroxide ion, [OH−], is related to the concentration of the hydrogen ion by Kw = [H+][OH−], therefore Substitution of the expression for [OH−] into the expression for Kb gives When Ka, Kb and Kw are determined under the same conditions of temperature and ionic strength, it follows, taking cologarithms, that pKb = pKw − pKa.

Because the relationship pKb = pKw − pKa holds only in aqueous solutions (though analogous relationships apply for other amphoteric solvents), subdisciplines of chemistry like organic chemistry that usually deal with nonaqueous solutions generally do not use pKb as a measure of basicity.

Often this is written as the hydronium ion H3O+, but this formula is not exact because in fact there is solvation by more than one water molecule and species such as H5O+2, H7O+3, and H9O+4 are also present.

[44] In aqueous solutions, homoconjugation does not occur, because water forms stronger hydrogen bonds to the conjugate base than does the acid.

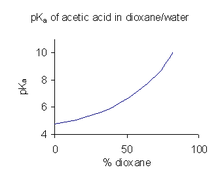

[46] In the example shown at the right, the pKa value rises steeply with increasing percentage of dioxane as the dielectric constant of the mixture is decreasing.

A universal, solvent-independent, scale for acid dissociation constants has not been developed, since there is no known way to compare the standard states of two different solvents.

[7] The increased acidity on adding an oxo group is due to stabilization of the conjugate base by delocalization of its negative charge over an additional oxygen atom.

The electron-withdrawing effect of the substituent makes ionisation easier, so successive pKa values decrease in the series 4.7, 2.8, 1.4, and 0.7 when 0, 1, 2, or 3 chlorine atoms are present.

This and other studies allowed substituents to be ordered according to their electron-withdrawing or electron-releasing power, and to distinguish between inductive and mesomeric effects.

[52][53] Alcohols do not normally behave as acids in water, but the presence of a double bond adjacent to the OH group can substantially decrease the pKa by the mechanism of keto–enol tautomerism.

The reason for this large difference is that when one proton is removed from the cis isomer (maleic acid) a strong intramolecular hydrogen bond is formed with the nearby remaining carboxyl group.

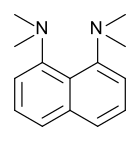

For example, the expected (by electronic effects of methyl substituents) and observed in gas phase order of basicity of methylamines, Me3N > Me2NH > MeNH2 > NH3, is changed by water to Me2NH > MeNH2 > Me3N > NH3.

Relative stabilization of methylammonium ions thus decreases with the number of methyl groups explaining the order of water basicity of methylamines.

[11] The standard enthalpy change can be determined by calorimetry or by using the van 't Hoff equation, though the calorimetric method is preferable.

The experimental determination of pKa values is commonly performed by means of titrations, in a medium of high ionic strength and at constant temperature.

This end-point is not sharp and is typical of a diprotic acid whose buffer regions overlap by a small amount: pKa2 − pKa1 is about three in this example.

When this is so, the solution is not buffered and the pH rises steeply on addition of a small amount of strong base.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) may be used to determine both a pK value and the corresponding standard enthalpy for acid dissociation.

For some polyprotic acids, dissociation (or association) occurs at more than one nonequivalent site,[4] and the observed macroscopic equilibrium constant, or macro-constant, is a combination of micro-constants involving distinct species.

[65] For example, the abovementioned equilibrium for spermine may be considered in terms of Ka values of two tautomeric conjugate acids, with macro-constant In this case

In pharmacology, ionization of a compound alters its physical behaviour and macro properties such as solubility and lipophilicity, log p).

This is exploited in drug development to increase the concentration of a compound in the blood by adjusting the pKa of an ionizable group.