Persian literature

There is thus Persian literature from Iran, Mesopotamia, Azerbaijan, the wider Caucasus, Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, Tajikistan and other parts of Central Asia, as well as the Balkans.

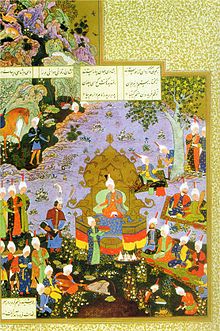

[6] Persian poets such as Ferdowsi, Saadi, Hafiz, Attar, Nezami,[7] Rumi[8] and Omar Khayyam[9][10] are also known in the West and have influenced the literature of many countries.

However, some essays in Pahlavi, such as "Ayin-e name nebeshtan" (Principles of Writing Book) and "Bab-e edteda’I-ye" (Kalileh o Demneh), have been considered as literary criticism (Zarrinkoub, 1959).

Works of the early era of Persian poetry are characterized by strong court patronage, an extravagance of panegyrics, and what is known as سبک فاخر "exalted in style".

In addition, some tend to group Naser Khosrow's works in this style as well; however true gems of this genre are two books by Saadi, a heavyweight of Persian literature, the Bustan and the Gulistan.

The most significant prose writings of this era are Nizami Arudhi Samarqandi's "Chahār Maqāleh" as well as Zahiriddin Nasr Muhammad Aufi's anecdote compendium Jawami ul-Hikayat.

The oldest surviving work of Persian literary criticism after the Islamic conquest of Persia is Muqaddame-ye Shahname-ye Abu Mansuri, which was written during the Samanid period.

It traces the historical development of the Persian language, providing a comprehensive resource to scholars and academic researchers, as well as describing usage in its many variations throughout the world.

Ferdowsi, together with Nezāmi, may have left the most enduring imprint on Georgian literature (...)[22]Despite that Asia Minor (or Anatolia) had been ruled various times prior to the Middle Ages by various Persian-speaking dynasties originating in Iran, the language lost its traditional foothold there with the demise of the Sassanian Empire.

[25] The educated and noble class of the Ottoman Empire all spoke Persian, such as sultan Selim I, despite being Safavid Iran's archrival and a staunch opposer of Shia Islam.

[30] The 16th-century Ottoman Aşık Çelebi (died 1572), who hailed from Prizren in modern-day Kosovo, was galvanized by the abundant Persian-speaking and Persian-writing communities of Vardar Yenicesi, and he referred to the city as a "hotbed of Persian".

Khayyam's line, "A loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou", is known to many who could not say who wrote it, or where: گر دست دهد ز مغز گندم نانی وز می دو منی ز گوسفندی رانی وانگه من و تو نشسته در ویرانی عیشی بود آن نه حد هر سلطانی gar(agar) dast dahad ze maghz-e gandom nāni va'z(va az) mey do mani ze gūsfandi rāni vāngah man-o tō neshaste dar vīrāni 'eyshi bovad ān na had-de har soltāni Ah, would there were a loaf of bread as fare, A joint of lamb, a jug of vintage rare, And you and I in wilderness encamped— No Sultan's pleasure could with ours compare.

The Persian poet and mystic Rumi (1207–1273) (known as Molana in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and as Mevlana in Turkey), has attracted a large following in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

More recently classical authors such as Hafez, Rumi, Araqi and Nizami Aruzi have been rendered into Swedish by the Iranist Ashk Dahlén, who has published several essays on the development of Persian literature.

During the last century, numerous works of classical and modern Persian literature have been translated into Italian by Alessandro Bausani (Nizami, Rumi, Iqbal, Khayyam), Carlo Saccone ('Attar, Sana'i, Hafiz, Nasir-i Khusraw, Nizami, Ahmad Ghazali, Ansari of Herat, Sa'di, Ayené), Angelo Piemontese (Amir Khusraw Dihlavi), Pio Filippani-Ronconi (Nasir-i Khusraw, Sa'di), Riccardo Zipoli (Kay Ka'us, Bidil), Maurizio Pistoso (Nizam al-Mulk), Giorgio Vercellin (Nizami 'Aruzi), Giovanni Maria D'Erme ('Ubayd Zakani, Hafiz), Sergio Foti (Suhrawardi, Rumi, Jami), Rita Bargigli (Sa'di, Farrukhi, Manuchehri, 'Unsuri), Nahid Norozi (Sohrab Sepehri, Khwaju of Kerman, Ahmad Shamlu), Faezeh Mardani (Forugh Farrokhzad, Abbas Kiarostami).

Given the social and political climate of Persia (Iran) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which led to the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906–1911, the idea that change in poetry was necessary became widespread.

This idea was propagated by notable literary figures such as Ali-Akbar Dehkhoda and Abolqasem Aref, who challenged the traditional system of Persian poetry in terms of introducing new content and experimentation with rhetoric, lexico-semantics, and structure.

Following the pioneering works of Ahmad Kasravi, Sadeq Hedayat and many others, the Iranian wave of comparative literature and literary criticism reached a symbolic crest with the emergence of Abdolhossein Zarrinkoub, Shahrokh Meskoob, Houshang Golshiri and Ebrahim Golestan.

In 1911, Mahmud Tarzi, who came back to Afghanistan after years of exile in Turkey and was influential in government circles, started a fortnightly publication named Saraj’ul Akhbar.

Saraj not only played an important role in journalism, it also gave new life to literature as a whole and opened the way for poetry to explore new avenues of expression through which personal thoughts took on a more social colour.

In time, the Kabul publication turned into a stronghold for traditional writers and poets, and modernism in Dari literature was pushed to the fringes of social and cultural life.

[33] Prominent novelists and short story writers from Afghanistan include Akram Osman, known especially for Real Men Keep Their Word (مرداره قول اس), written in part in Kabuli dialect, and Rahnaward Zaryab.

Some of Tajikistan's prominent names in Persian literature are Golrokhsar Safi Eva,[34] Mo'men Ghena'at,[35] Farzaneh Khojandi,[36] Bozor Sobir, and Layeq Shir-Ali.

[38] Contemporary Persian literary criticism reached its maturity after Sadeq Hedayat, Ebrahim Golestan, Houshang Golshiri, Abdolhossein Zarrinkoub and Shahrokh Meskoob.

[citation needed] Jalal Homaei, Badiozzaman Forouzanfar and his student, Mohammad Reza Shafiei-Kadkani, are other notable figures who have edited a number of prominent literary works.

Mohammad Taghi Bahar had the title "king of poets" and had a significant role in the emergence and development of Persian literature as a distinct institution in the early part of the 20th century.

His artistry was not confined to removing the need for a fixed-length hemistich and dispensing with the tradition of rhyming but focused on a broader structure and function based on a contemporary understanding of human and social existence.

It relied on the natural function inherent within poetry itself to portray the poet’s solidarity with life and the wide world surrounding him or her in specific and unambiguous details and scenes.

In the structure of Sepid poetry, in contrast to the prosodic and Nimai’ rules, the poem is written in more "natural" words and incorporates a prose-like process without losing its poetic distinction.

Éditions Bruno Doucey published a selection of forty-eight poems by Garus Abdolmalekian entitled Our Fists under the Table (2012),[53] translated into French by Farideh Rava.