Thai literature

Terwiel, this process occurred with an accelerated pace during the reign of King Boromma-trailokkanat (1448-1488) who reformed Siam's model of governance by turning the Siamese polity into an empire under the mandala feudal system.

It allowed Siamese poets to compose in different poetical styles and mood—from playful and humorous rhymed verses, to romantic and elegant khlong and to polished and imperious chan prosodies which were modified from classical Sanskrit meters.

Terwiel notes, citing a 17th-century Thai text book Jindamanee, that scribes and common Siamese men, too, were encouraged to learn basic Pali and Sanskrit terms for career advancement.

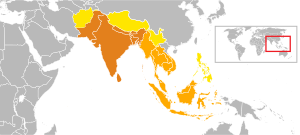

[11] The Siamese drama and classical dance later spread throughout mainland Southeast Asia and influenced the art in neighboring countries, including Burma's own version of Ramayana, Cambodia, and Laos.

The Trai Phum Phra Ruang explains the composition of the universe, which, according to the Theravada Buddhist Thai, consists of three different "worlds" or levels of existence and their respective mythological inhabitants and creatures.

The year of composition was dated at 1345 CE,[citation needed] whereas the authorship is traditionally attributed to the then designated heir to the throne and later King LiThai (Thai: พญาลิไทย) of Sukhothai.

[citation needed] A lilit (Thai: ลิลิต) is a literary format which interleaves poetic verses of different metrical nature to create a variety of pace and cadence in the music of the poetry.

It serves also as an important historical account of the war between Siam and Lan Na, as well as an evidence of the Siamese's theory of kingship that was evolving during the reign of Borommatrailokkanat.

In 1492, King Borommatrailokkanat authorized a group of scholars to write a poem based on the story of Vessantara Jataka, believed to be the greatest of Buddha's incarnations.

Since nirat poems record what the poet sees or experiences during his journey, they represent an information source for the Siamese culture as well as history in the premodern time.

[16] By the late period of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, it had attained the current shape as a long work of epic poem with the length of about 20,000 lines, spanning 43 samut thai books.

"[16]: 14 KCKP additionally contains rich and detailed accounts of the traditional Thai society during the late Ayutthaya period, including religious practices, superstitious beliefs, social relations, household management, military tactics, court and legal procedures etc.

To this day, KCKP is regarded as the masterpiece of Thai literature for its high entertainment value - with engaging plots even by modern standard - and its wealth of cultural knowledge.

Marveling at the sumptuous milieu of old Siamese customs, beliefs, and practices in which the story takes place, William J. Gedney, a philologist specialized in Southeast Asian languages, commented that: “The quality of much of this work is superb, often entrancing for its elegance, grace, and vitality.

One cannot help feeling that this body of traditional Thai poetry is among the finest artistic creations in the history of mankind.”[17] A complete English prose translation of KCKP was published by Chris Baker and P. Phongpaichit in 2010.

[18] Another popular character among Ayutthaya folktales is the trickster, the best known is Sri Thanonchai (Thai: ศรีธนญชัย), usually a heroic figure who teaches or learns moral lessons and is known for his charm, wit, and verbal dexterity.

[20] The Legend of Phra Malai (Thai: พระมาลัยคำหลวง) is a religious epic adventure composed by Prince Thammathibet, one of the greatest Ayutthayan poets, in 1737, although the story's origin is assumed to be much older, being based on a Pali text.

[21] Phra Malai then returns to the world of the living and tells people the story of the underworld, reminding listeners to make good merits and to adhere to the buddhist's teachings in order to avoid damnation.

Following Buddhist precepts, obtaining merit, and attending performances of the Vessantara Jataka all counted as virtues that increased the chances of a favourable rebirth, or Nirvana in the end.

Other notable literary works of the mid and late Ayutthaya Kingdom include: With the arrival of the Rattanakosin era, Thai literature experienced a rebirth of creative energy and reached its most prolific period.

Sunthorn Phu consciously moved away from a difficult and stately language of court poetry and composed mostly in a popular poetical form called klon suphap (Thai: กลอนสุภาพ).

There were also other masterpieces of Klon-suphap poem from this era, such as "Kaki Klon Suphap" – which influences the Cambodian Kakey – by Chao Phraya Phrakhlang (Hon).

It relates the adventures of the eponymous protagonist, Prince Aphai Mani, who is trained in the art of music such that the songs of his flute could tame and disarm men, beasts, and gods.

While in exile, Phra Aphai is kidnapped by a female Titan (or an ogress) named Pii Sue Samut ('sea butterfly'; Thai: ผีเสื้อสมุทร) who falls in love with him after she hears his flute music.

Phra Aphai slays Pii Sue Samut (the ogress) with the song of his flute and continues his voyage; he suffers more shipwrecks, is rescued, and then falls in love with a princess named Suwanmali.

Also, unlike other classical Thai epic poems, Phra Aphai Mani depicts various exploits of white mercenaries and pirates which reflects the ongoing European colonization of Southeast Asia in the early-19th century.

[25] In a literary sense, however, Phra Aphai Mani has been suggested by other Thai academics as being inspired by Greek epics and Persian literature, notably the Iliad, the Odyssey, the Argonauts, and Thousand and One Nights.

Others have suggested that Nang Laweng may have been inspired by a story of a Christian princess, as recounted in Persia's Thousand and One Nights, who falls in love with a Muslim king.

[25] All of this suggests that Sunthorn Phu was a Siamese bard with a bright and curious mind who absorbed, not only the knowledge of contemporary seafaring and Western inventions, but also stories of Greek classical epics from learned Europeans.

Sunthorn Phu exercised his "copyright" by allowing people to make copies of his nithan poems (Thai: นิทานคำกลอน), such as Phra Aphai Mani, for a fee.