Iron Age

In the archaeology of the Americas, a five-period system is conventionally used instead; indigenous cultures there did not develop an iron economy in the pre-Columbian era, though some did work copper and bronze.

The term "Iron Age" in the archaeology of South, East, and Southeast Asia is more recent and less common than for Western Eurasia.

The earliest-known meteoric iron artifacts are nine small beads dated to 3200 BC, which were found in burials at Gerzeh in Lower Egypt, having been shaped by careful hammering.

[citation needed] Only with the capability of the production of carbon steel does ferrous metallurgy result in tools or weapons that are harder and lighter than bronze.

Whilst terrestrial iron is abundant naturally, temperatures above 1,250 °C (2,280 °F) are required to smelt it, impractical to achieve with the technology available commonly until the end of the second millennium BC.

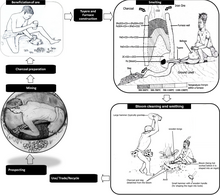

[11] In addition to specially designed furnaces, ancient iron production required the development of complex procedures for the removal of impurities, the regulation of the admixture of carbon, and the invention of hot-working to achieve a useful balance of hardness and strength in steel.

The earliest tentative evidence for iron-making is a small number of iron fragments with the appropriate amounts of carbon admixture found in the Proto-Hittite layers at Kaman-Kalehöyük in modern-day Turkey, dated to 2200–2000 BC.

Akanuma (2008) concludes that "The combination of carbon dating, archaeological context, and archaeometallurgical examination indicates that it is likely that the use of ironware made of steel had already begun in the third millennium BC in Central Anatolia".

[18] Modern archaeological evidence identifies the start of large-scale global iron production about 1200 BC, marking the end of the Bronze Age.

Anthony Snodgrass suggests that a shortage of tin and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean about 1300 BC forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze.

[19][20] Many bronze implements were recycled into weapons during that time, and more widespread use of iron resulted in improved steel-making technology and lower costs.

It was long believed that the success of the Hittite Empire during the Late Bronze Age had been based on the advantages entailed by the "monopoly" on ironworking at the time.

The explanation of this would seem to be that the relics are in most cases the paraphernalia of tombs, the funeral vessels and vases, and iron being considered an impure metal by the ancient Egyptians it was never used in their manufacture of these or for any religious purposes.

[24] A sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.

For much of Europe, the period came to an abrupt local end after conquest by the Romans, though ironworking remained the dominant technology until recent times.

Iron working was introduced to Europe during the late 11th century BC,[33] probably from the Caucasus, and slowly spread northwards and westwards over the succeeding 500 years.

This settlement (fortified villages) covered an area of 3.8 hectares (9.4 acres), and served as a Celtiberian stronghold against Roman invasions.

A number of amphoras (containers usually for wine or olive oil), coins, fragments of pottery, weapons, pieces of jewelry, as well as ruins of a bath and its pedra formosa (lit.

Important non-precious husi style metal finds include iron tools found at the tomb at Guwei-cun of the 4th century BC.

Distinguishing characteristics of the Yayoi period include the appearance of new pottery styles and the start of intensive rice agriculture in paddy fields.

Iron objects were introduced to the Korean peninsula through trade with chiefdoms and state-level societies in the Yellow Sea area during the 4th century BC, just at the end of the Warring States Period but prior to the beginning of the Western Han dynasty.

The complex chiefdoms were the precursors of early states such as Silla, Baekje, Goguryeo, and Gaya[50][52] Iron ingots were an important mortuary item and indicated the wealth or prestige of the deceased during this period.

Archaeological sites in India, such as Malhar, Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila, Lahuradewa, Kosambi and Jhusi, Allahabad in present-day Uttar Pradesh show iron implements in the period 1800–1200 BC.

The name "Ko Veta" is engraved in Brahmi script on a seal buried with the skeleton and is assigned by the excavators to the 3rd century BC.

[65] The earliest undisputed deciphered epigraphy found in the Indian subcontinent are the Edicts of Ashoka of the 3rd century BC, in the Brahmi script.

Sa Huynh beads were made from glass, carnelian, agate, olivine, zircon, gold and garnet; most of these materials were not local to the region and were most likely imported.

Conversely, Sa Huynh produced ear ornaments have been found in archaeological sites in Central Thailand, as well as the Orchid Island.

[72]: 211–217 Early evidence for iron technology in Sub-Saharan Africa can be found at sites such as KM2 and KM3 in northwest Tanzania and parts of Nigeria and the Central African Republic.

[76] Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the Nok culture of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.

[79] Instances of carbon steel based on complex preheating principles were found to be in production around the 1st century AD in northwest Tanzania.