Prehistory of Southeast Europe

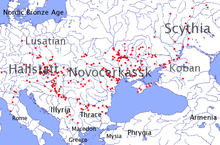

The prehistory of Southeast Europe, defined roughly as the territory of the wider Southeast Europe (including the territories of the modern countries of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, and European Turkey) covers the period from the Upper Paleolithic, beginning with the presence of Homo sapiens in the area some 44,000 years ago, until the appearance of the first written records in Classical Antiquity, in Greece.

[1] It is descended from the older Linear A, an undeciphered earlier script used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek.

Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Kydonia,[2] Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae,[3] but disappeared with the fall of the Mycenean civilisation during the Late Bronze Age collapse.

Human prehistory in Southeast Europe is conventionally divided into smaller periods, such as Upper Paleolithic, Holocene Mesolithic/Epipaleolithic, Neolithic Revolution, expansion of Proto-Indo-Europeans, and Protohistory.

For example, depending on interpretation, protohistory might or might not include Bronze Age Greece (3000–1200 BC),[4] Minoan, Mycenaean, Thracian and Venetic cultures.

According to Douglass W. Bailey:[7] it is important to recognize that the Southeastern Europe Upper Palaeolithic was a long period containing little significant internal change.

In the late Pleistocene, various components of the transition–material culture and environmental features (climate, flora, and fauna) indicate continual change, differing from contemporary points in other parts of Europe.

In this sense, the material culture and natural environment of the region of the late Pleistocene and the early Holocene were distinct from other parts of Europe.

Douglass W. Bailey writes in Balkan Prehistory: Exclusion, Incorporation and Identity: “Less dramatic changes to climate, flora and fauna resulted in less dramatic adaptive, or reactive, developments in material culture.” Thus, in speaking about southeastern Europe, many classic conceptions and systematizations of human development during the Palaeolithic (and then by implication the Mesolithic) should not be considered correct in all cases.

The first skull, scapula and tibia remains were found in 1952 in Baia de Fier, in the Muierii Cave, Gorj County in the Oltenia province, by Constantin Nicolaescu-Plopşor.

According to Douglass W. Bailey:[17] It is equally important to recognize that the Balkan upper Palaeolithic was a long period containing little significant internal change.

Regions that experienced less environmental impact during the last ice age have a much less apparent and straightforward change, and occasionally are marked by an absence of sites from the Mesolithic era.

At Ostrovul Banului, the Cuina Turcului rock shelter in the Danube gorges and in the nearby caves of Climente, there are finds that people of that time made relatively advanced bone and lithic tools (i.e. end-scrapers, blade lets, and flakes).

There is a 4,000-year gap between the latest Upper Palaeolithic material (13,600 BP at Témnata Dupka) and the earliest Neolithic evidence presented at Gǎlǎbnik (the beginning of the 7th millennium BC).

Activities began to be concentrated around individual sites where people displayed personal and group identities using various decorations: wearing ornaments and painting their bodies with ochre and hematite.

As regards personal identity D. Bailey writes, “Flint-cutting tools as well as time and effort needed to produce such tools testify to the expressions of identity and more flexible combinations of materials, which began to be used in the late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic.” The aforementioned allows us to speculate whether or not there was a period which could be described as Mesolithic in Southeastern Europe, rather than an extended Upper Palaeolithic.

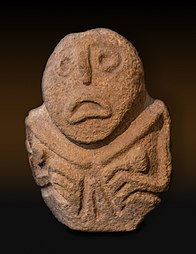

Southeastern Europe was the site of major Neolithic cultures, including Butmir, Vinča, Varna, Karanovo, Hamangia and Sesklo.

Neolithic settlements are also spotted in modern day Greece, trading routes that are based in the late Mesolithic period exist all over the Aegean sea.

Some major settlements of Neolithic Greece are Sesklo, Dimini, Early Knossos and Nea Nikomedeia close to Krya Vrysi.

The name Illyrii was originally used to refer to a people occupying an area centered on Lake Skadar, situated between Albania and Montenegro (see List of ancient tribes in Illyria).

The term Illyria was subsequently used by the Greeks and Romans as a generic name to refer to different peoples within a well defined but much greater area.