Thracians

[3] Around the 5th millennium BC, the inhabitants of the eastern region of the Balkans became organized in different groups of indigenous people that were later named by the ancient Greeks under the single ethnonym of "Thracians".

[13] According to Greek and Roman historians, the Thracians were uncivilized and remained largely disunited, until the establishment of their first permanent state the Odrysian kingdom in the very beginning of 5th century BC, founded by king Teres I, exploiting the collapse of the Persian presence in Europe due to failed invasion of Greece in 480–79.

[26] According to one theory, their ancestors migrated in three waves from the northeast: the first in the Late Neolithic, forcing out the Pelasgians and Achaeans, the second in the Early Bronze Age, and the third around 1200 BC.

[24] The lack of written archeological records left by Thracians suggests that the diverse topography did not make it possible for a single language to form.

[27] Thracians inhabited parts of the ancient provinces of Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Beotia, Attica, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia, Mysia, Pannonia, and other regions of the Balkans and Anatolia.

Due to the lack of historical records that predate Classical Greece it's presumed that the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the 5th century BC.

[38] The French historian Victor Duruy further notes that they "considered husbandry unworthy of a warrior, and knew no source of gain but war and theft".

According to ancient Roman sources, the Dii[48] were responsible for the worst[49] atrocities in the Peloponnesian War, killing every living thing, including children and dogs in Tanagra and Mycalessos.

[60] Other ancient writers who described the hair of the Thracians as red include Hecataeus of Miletus,[61] Galen,[62] Clement of Alexandria,[63] and Julius Firmicus Maternus.

Once Darius had reached the Danube, he crossed the river and campaigned against the Scythians, after which he returned to Anatolia through Thrace and left a large army in Europe under the command of his general Megabazus.

The last endeavours of Megabazus included his the conquest of the area between the Strymon and Axius rivers, and at the end of his campaign, the king of Macedonia, Amyntas I, accepted to become a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire.

In the interior, the Western border of the satrapy consisted of the Axius river and the Belasica-Pirin-Rila mountain ranges till the site of modern-day Kostenets.

[79] Once the Ionian Revolt had been fully quelled, the Achaemenid general Mardonius crossed the Hellespont with a large fleet and army, re-subjugated Thrace without any effort and made Macedonia full part of the satrapy of Skudra.

Thanks to the Thracians co-operating with the Persians by sending supplies and military reinforcements down the Hebrus river route, Achaemenid authority in central Thrace lasted until around 465 BC, and the governor Mascames managed to resist many Greek attacks in Doriscus until then.

[79] Around this time, Teres I, the king of the Odrysae tribe, in whose territory the Hebrus flowed, was starting to organise the rise of his kingdom into a powerful state.

[citation needed] By the 5th century BC, the Thracian population was large enough that Herodotus called them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians), and potentially the most powerful, if not for their lack of unity.

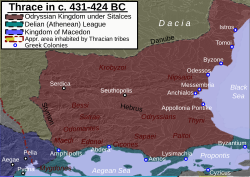

[citation needed] After the Persians withdrew from Europe and before the expansion of the Kingdom of Macedon, Thrace was divided into three regions (east, central, and west).

[91][92] The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the 4th century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years.

[citation needed] In 336 BC, Alexander the Great began recruiting thracian cavalry and javelin men in his army, who accompnied him on his continuous conquest to expand the borders of the Macedonian Empire.

As described by Xenophon, and Menander in Aspis, after the slaves were captured in raids, their actual enslavement took place when they were resold through slave-dealers to Athenians and other slaveowners throughout Greece.

The names given to slaves in the comedies often had a geographical link, thus Thratta, used by Aristophanes in The Wasps, The Acharnians, and Peace, simply meant a Thracian woman.

[citation needed] After Rhoemetalces III of the Thracian Kingdom of Sapes was murdered in AD 46 by his wife, Thracia was incorporated as an official Roman province to be governed by Procurators, and later Praetorian prefects.

The lack of large urban centers made Thracia a difficult place to manage, but eventually the province flourished under Roman rule.

German historian Gottfried Schramm speculated that the Albanians derived from the Christianized Thracian tribe Bessi, after their remnants were allegedly pushed by Slavs and Bulgars during the 9th century westwards into modern day Albania.

[122] In myth, Orpheus rebuked the sexual advances of the Bistones women after the death of Eurydice, and was killed for not engaging in the activities promoted by the followers of Dionysus.

[citation needed] A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in 2019 examined the mtDNA of 25 Thracian remains in Bulgaria from the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC.

[135] The dominant stance of history and archaeology as the two main disciplines dealing with the Thracians as a subject of research has been succeeded by a clear shift towards new multidisciplinary and more inclusive scientific perspectives.

An example of this new trend was the large-scale multidisciplinary project "Thracians – Genesis and Development of the Ethnos, Cultural Identities, Civilization Relations and Heritage of the Antiquity", launched in 2016 in Bulgaria.

The project was the first comprehensive study of the Thracian heritage including 72 scholars from 18 institutes of the Bulgarian Academy of Science, as well as researchers from Canada, Italy, Germany, Japan and Switzerland.

The project studied 13 scientific themes among which: formation of the Thracian ethnos, outlining of its ethno-cultural territory, continuity of the gene pool and related DNA studies, architectural, botanical, microbiological, astronomical, acoustic and linguistic aspects, mining and ceramics technologies, food and drink customs, that resulted in an extensively illustrated book including 33 scientific articles.