Iron Confederacy

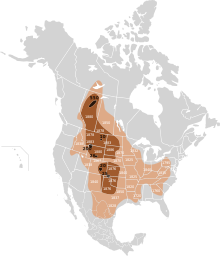

This confederacy included various individual bands that formed political, hunting and military alliances in defense against common enemies.

The decline of the fur trade and the collapse of the bison herds sapped the power of the Confederacy after the 1860s, and it could no longer act as a barrier to U.S. and Canadian expansion.

They became a separate people from their closest linguistic cousins, the Yanktonai Dakota, sometime prior to 1640 when they are first mentioned by Europeans in the Jesuit Relation.

Prior to this the Cree had been at the northwestern edge of a trade system linked to the French, from which they received only the secondhand goods others were ready to discard.

[5] The earliest written record of the military and political relations of the nations west of Hudson's Bay comes from Henry Kelsey's journal c. 1690–1692.

There is clear evidence of them as a separate group from 1754–1755 when Anthony Henday wrote of camping with "Stone" families near present-day Red Deer, Alberta.

They joined forces in pushing the Blackfeet, Bloods, and Piegan southwestward out of the plains bordering Saskatchewan river, and up to the termination of inter-tribal warfare remained constant enemies of these other Algonquians.

The Woods Cree had little, if any, part in this warfare with the Blackfeet and the Sioux; their operations were limited to dispossessing the Athapascans of their territory between the Saskatchewan and Athabasca lake.

[17] In 1754 Henday reported that he was able to buy a horse from the Assiniboine camped near present-day Battleford, Saskatchewan, and was the first European witness to Cree-Assiniboine trade with the "Archithinue" (Blackfoot Confederacy).

[18] In 1772, Mathew Cocking reported that the Cree and Assiniboine with whom he travelled were always alarmed when they saw an unknown horse, fearing that they might belong to the Snakes.

These emerging Plains Cree were initially allies of the Blackfoot, helping them to drive the Kootenay and Snakes across the Rocky Mountains.

[23] In 1846, travelling artist Paul Kane identified a man he met at Fort Pitt, Kee-a-kee-ka-sa-coo-way, as "head chief" of the Cree, though it is doubtful that any such title existed.

Kane mentions a man named Mukeetoo as his associate, but historians believe this person to be Black Powder, who was Plains Ojibwa rather than Cree.

[24] By the 1850s, two bands, the "Cree-Assiniboine" or (also called the "Cree-speaking Assiniboine" or the "Young Dogs"), and the Qu'Appelle were established in the region between Wood Mountain and the Cypress Hills and traded on both sides of the international border.

They then proceed across the Missouri up the Yellow Stone, and return to the Saskatchewan and Athabaska as winter approaches, by the flanks of the Rocky Mountains.This meant that many Plains peoples would often rely on the same herd; overhunting by one party (or European settlers) affected them all in a tragedy of the commons.

The Métis were not able to rally the Cree or Assiniboine to their cause, and the Wolseley expedition instead put down the Red River Resistance with military force during the annual buffalo hunt rather than overseeing the implementation of the Manitoba Act as had been negotiated.

The decline of the buffalo had become a subsistence crisis for the member bands of the Confederacy by the 1870s which led them to seek help from the Canadian government.

Notably, these were negotiated separately from Treaty 7 (1877) with the Blackfoot Confederacy, showing that the Canadian government recognized the differences between the two groups.

Under the terms of these treaties, the member bands of the Iron Confederacy accepted the presence of Canadian settlers on their lands in exchange for emergency and ongoing aid to deal with the starvation being experienced by the plains people due to the disappearance of the bison herds.

[20] Governmental opinion in both Canada and the US quickly turned against the previous policy of allowing the free movement of native people across the frontier.

Authorities in both countries wanted natives to "civilize", by ending their nomadic hunting traditions, and take up agriculture on reserves, thereby opening the land up for white ranchers and farmers.

[20] Cree and Metis parties continued to hunt in Montana until late 1881 when the US Army began to arrest and deport them, effectively cutting them off from one of the last remaining bison populations and ensuring their dependence on government-supplied rations.

Many Cree and Assiniboine were dissatisfied with their situation, believing that the Canadian government was not living up to its treaty obligations,[20] but it was not a straightforward decision to take up arms.

[20] The decline of the buffalo, the treaties it signed with the Queen, and its fighters' defeat in the First Nations portion of the North-West Rebellion heralded, and contributed, to the Iron Confederacy's growing impotence as an economic, social and sovereign unit.