Maritime fur trade

[1][2] The trade mostly serviced the market in Qing China, which imported furs and exported tea, silks, porcelain, and other Chinese goods, which were then sold in Europe and in the United States.

As the sea-otter population became depleted over time, the maritime fur trade diversified and transformed, tapping new commodities, while continuing to focus on the Northwest Coast of North America and on markets in China.

A sort of triangular trade network emerged linking the Pacific Northwest coast, China, the Hawaiian Islands (first generally known to the Western world following James Cook's visit in 1778[19]), Britain, and the United States (especially New England).

Settler colonialism in the South Pacific resulted during the course of the 19th century in genocides (in fur-sources like Tasmania and the Chatham Islands) and in cultural disruption and temporary numerical decline for the Māori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand.

In Britain's Australian colonies, furs became the earliest international export items[31] and fuelled the first in a series of economic booms[32] and busts,[33] while boosting convict capitalism.

[36] Fashionable popularity fed the market demand for sea-otter pelts in China, Europe and America, and played a role in entrepreneurs hunting the species to the point of disappearance.

[43][44] While Russians developed the maritime fur-trade based on sea-otter pelts, societies from eastern North America gradually moved their largely beaver-based fur-harvesting enterprises further and further westward.

[48] The natural ecosystems that came to rely on the beavers for dams, water and other vital needs were also devastated leading to ecological destruction, environmental change, and drought in certain areas.

The killing of beavers had catastrophic effects for many species living in the Pacific coastal regions of northern North America - including otters, fish, and bears - the water, soil, ecosystems and resources were devastated by the maritime fur trade.

The Northwest Coast is very complex — a "labyrinth of waters", according to George Simpson[61]— with thousands of islands, numerous straits and fjords, and a mountainous, rocky, and often very steep shoreline.

[61] Early explorations before the maritime fur trade era—by Juan Pérez, Bruno de Heceta, Bogeda y Quadra, and James Cook—produced only rough surveys of the coast's general features.

Notable Russian traders in the early years of the trade include Nikifor Trapeznikov (who financed and participated in 10 voyages between 1743 and 1768), Maksimovich Solov'ev, Stepan Glotov, and Grigory Shelikhov.

[74] James King, one of the commanders after Cook's death, wrote, "the advantages that might be derived from a voyage to that part of the American coast, undertaken with commercial views, appear to me of a degree of importance sufficient to call for the attention of the public."

[76] British interest in the maritime fur trade peaked between 1785 and 1794, then declined as the French Revolutionary Wars diminished Britain's available manpower and investment capital.

Although the SSC was moribund by the late 18th century, it had been granted the exclusive right to British trade on the entire western coast of the Americas from Cape Horn to Bering Strait and for 300 leagues (around 900 mi (1,400 km)) out into the Pacific Ocean.

A number of vessels sailed to Nootka Sound, including Argonaut under James Colnett, Princess Royal, under Thomas Hudson, and Iphigenia Nubiana and North West America.

From the first decade of the 19th century until 1841 American ships visited Sitka regularly, trading provisions, textiles, and liquor for fur seal skins, timber, and fish.

Aemelius Simpson of the Hudson's Bay Company wrote in 1828 that American traders on coast trafficked in slaves, "purchasing them at a cheap rate from one tribe and disposing of them to others at a very high profit."

Before the 19th century, Chinese demand for Western raw materials or manufactured goods was small, but bullion (also known as specie) was accepted, resulting in a general drain of precious metals from the West to China.

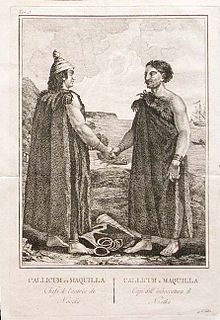

Many significant trading sites were on the Queen Charlotte Islands, including Cloak Bay,[135] Masset,[136] Skidegate,[137] Cumshewa,[138] Skedans, and Houston Stewart Channel,[139] known as "Coyah's Harbor", after Chief Koyah.

Even though Perkins and Company took 25% of the proceeds the arrangement was still about 50% more profitable than using British ships and selling furs in Canton through the EIC for bills payable on London and returning from China with no cargo.

At first the system of shipping furs via the American Perkins and Company was continued, but in 1822 the United States Customs Service imposed a heavy ad valorem duty on the proceeds.

Simpson decided that the "London ships", which brought goods to Fort Vancouver and returned to England with furs, should arrive early enough to make a coasting voyage before departing.

[151] The increase in trade, and new items had a significant impact on First Nations material cultures, seeing the rise of such traditions as fabric appliqué (Button Blankets), metalwork (Northwest Coast engraved silver jewelry originated around this time as Native craftsmen learned to make jewelry from coins), and contributed to a cultural fluorescence with the advent of improved (iron) tools that saw the creative of more and larger carvings (such as totem poles).

[151] After the early 19th century, Indigenous cultures on the coast suffered under increasing colonization, colonial rule, land seizure, forced relocations, missionization, ethnic cleansing, and major population loss from repeated epidemics.

[159] Many exotic foodstuffs were introduced to the Hawaiian Islands during the early trading era, including plants such as beans, cabbage, onions, squash, pumpkins, melons, and oranges, as well as cash crops like tobacco, cotton, and sugar.

These health issues, plus warfare related to the unification of the islands, droughts, and sandalwooding taking precedence over farming all contributed to an increase in famines and a general population decline.

Goods exported included furs, rum, ammunition, ginseng, lumber, ice, salt, Spanish silver dollars, iron, tobacco, opium, and tar.

The accumulation of large amounts of capital in short time contributed to American industrial and manufacturing development, which was compounded by rapid population growth and technological advancements.

In light of the decline of the fur trade and a post-Napoleonic depression in commerce, capital shifted "from wharf to waterfall", that is, from shipping ventures to textile mills (which were originally located where water power was available).