Irrigation in viticulture

While climate and humidity play important roles, a typical grape vine needs 25-35 inches (635-890 millimeters) of water a year, occurring during the spring and summer months of the growing season, to avoid stress.

In many Old World wine regions, natural rainfall is considered the only source for water that will still allow the vineyard to maintain its terroir characteristics.

Many New World wine regions such as Australia and California regularly practice irrigation in areas that couldn't otherwise support viticulture.

Archaeologists describe it as one of the oldest practices in viticulture, with irrigation canals discovered near vineyard sites in Armenia and Egypt dating back more than 2600 years.

[4] It is possible that the knowledge of irrigation helped viticulture spread from these areas to other regions, due to the potential for the grapevine to grow in soils too infertile to support other food crops.

With the development of more cost efficient and less labor-intensive ways of watering the vines, vast tracts of very sunny but dry lands were able to be converted into wine-growing regions.

However, if water is severely lacking then that internal temperature could jump nearly 18 °F (10 °C) warmer than the surrounding air which leads the vine to develop heat stress.

[2] A typical vineyard in a hot, dry climate can lose as much as 1,700 U.S. gallons (6,400 L; 1,400 imp gal) of water per vine through evapotranspiration during the growing season.

For example, Tuscany receives an average of 8 inches (200 mm) of rainfall during the months of April through June[6] - the period that includes flowering and fruit set, when the water is most crucial.

While fluctuations in rainfall do occur, the amount of natural precipitation, combined with water holding capacity of soil, is typically sufficient to result in healthy harvest.

The difference from the average mean temperature of its coldest and hottest months can be quite significant with moderate precipitation that usually occurs in the winter and early spring.

Examples of continental climates that use supplemental irrigation include the Columbia Valley of Washington State and the Mendoza wine region of Argentina.

Many maritime regions, such as Rias Baixas in Galicia, Bordeaux and the Willamette Valley in Oregon, suffer from the diametric problem of having too much rain during the growing season.

The term "field capacity" is used to describe the maximum amount of water that deeply moistened soil will retain after normal drainage.

Nowadays, precision agriculture uses high technology in the field, providing the producers with accurate measurements of the water needs of any specific vine.

Similarly, gypsum block placed throughout the vineyard contain an electrode that can be used to detect the electrical resistance that occurs as the soil dries and water is released by evaporation.

In the early history of the Chilean wine industry, flood irrigation was widely practiced in the vineyards using melted snow from the Andes Mountains channeled down to the valleys below.

With insufficient water, many of the vine's important physiological structures, including photosynthesis that contributes to the development of sugars and phenolic compounds in the grape, can shut down.

The key to irrigation is to provide just enough water for the plant to continuing function without encouraging vigorous growth of new shoots and shallow roots.

[1] After fruit set, the water needs for the vine drop and irrigation is often withheld till the period of veraison when the grapes begin to change color.

This period of "water stress" encourages the vine to concentrate its limited resources into lower yields of smaller berries creating a favorable skin to juice ratio that is often desirable in quality wine production.

Even if the berries do not crack or burst, the rapid swelling of water will cause a reduce concentration in sugars and phenolic compounds in the grape producing wines with diluted flavors and aromas.

When a grapevine goes into water stress one of its first functions is to reduce the growth of new plant shoots which compete with the grape clusters for nutrients and resources.

As the skin is filled with color phenols, tannin and aroma compounds, the increase in skin-to-juice ratio is desirable for the potential added complexity the wine may have.

The grapevines in many Mediterranean climates such as Tuscany in Italy and the Rhone Valley in France experience natural water stress due to the reduced rainfall that occurs during the summer growing season.

[16] Of the criticisms leveled towards irrigation, the most common is that it disrupts the natural expression of terroir in the land as well as the unique characteristics that comes with vintage variation.

[12] Other criticisms center around the broader environmental impact of irrigation on both the ecosystem around the vineyard as well as the added strain on global water resources.

[17] In 2007, concerns about ecological damage to the Russian River caused government officials in California to take similar measures to cut back water supplies and promote more efficient irrigation practices.

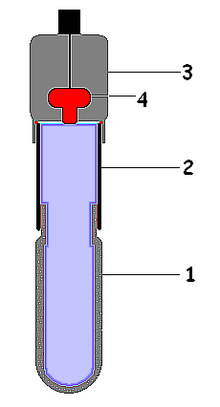

Commonly used in drip irrigation systems, this method allows similarly regulate control over how precisely how much fertilizer and nutrients that each vine receives.

One preventive measure against frost damage is to use the sprinkler irrigation system to coat the vines with a protective layer of water that freezes into ice.