Isan language

[3] The Lao language has had a long presence in Isan, arriving with migrants who followed the river valleys into Southeast Asia from southern China some time in the 8th to 10th centuries.

[5][6] However, with attitudes toward regional cultures becoming more relaxed in the late 20th century onwards, increased research into the language by Thai academics at Isan universities and an ethno-political stance often at odds with Bangkok, some efforts to help stem the slow disappearance of the language are beginning to take root, fostered by a growing awareness and appreciation of local culture, literature and history.

Lao and Thai, despite separate development, were pushed closer together due to proximity and adoption of the same Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali loan words.

[11] As a result, younger people have adopted the neologism Isan to describe themselves and their language, as it conveniently avoids ambiguity with the Laotian Lao as well as association with movements, historical and current, that tend to be leftist and at odds with the central government in Bangkok.

The peaks of the Phetsabun and Dong Phanya Nyen mountains to the west and the Sankamphaeng to the southwest separate the region from the rest of Thailand and the Damlek ridges forming the border with Cambodia.

Outside of Thailand, it is likely that Isan speakers can also be found in the United States, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan and Germany which house the largest populations of Overseas Thai.

The end of local autonomy and the presence of foreign troops led the Lao people to rebel under the influence of millennialist cult leaders or phu mi bun (ผู้มีบุญ, ຜູ້ມີບຸນ, /pʰȕː míː bùn/) during the Holy Man's Rebellion (1901—1902), the last united Lao resistance to Siamese rule, but the rebellion was brutally suppressed by Siamese troops and the reforms were fully implemented in the region shortly afterward.

The unofficial use of Lao to refer to them was discouraged, and the term 'Isan', originally just a name of the southern part of the 'Lao Monthon', was extended to the entire region, its primary ethnic group and language.

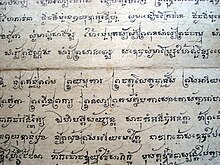

Monks still taught young boys to read the Tai Noi script written on palm-leaf manuscripts since there were no schools, passages from old literature were often read during festivals and traveling troupes of mo lam and shadow puppet performers relied on written manuscripts for the lyrics to poetry and old stories set to song and accompanied by the khaen alone or alongside other local instruments.

Most of these reforms were implemented by Plaek Phibunsongkhram, who changed the English name of Siam to 'Thailand' and whose ultra-nationalistic policies would mark Thailand during his rule from 1938 to 1944 and 1948–1957.

Numerous temples had their libraries seized and destroyed, replacing the old Lao religious texts, local histories, literature and poetry collections with Thai-script, Thai-centric manuscripts.

This severed the Isan people from knowledge of their written language, shared literary history and ability to communicate via writing with the left bank Lao.

In tandem with its removal from education and official contexts, the Thai language made a greater appearance in people's lives with the extension of the railroad to Ubon and Khon Kaen and with it the telegraph, radio and a larger number of Thai civil servants, teachers and government officials in the region that did not learn the local language.

Roads were finally built into the region, making Isan no longer unreachable for much of the year, and the arrival of television with its popular news broadcasts and soap operas penetrated into people's homes at this time.

As lands new lands to clear for cultivation were no longer available, urbanization began to occur, as well as the massive seasonal migration of Isan people to Bangkok during the dry season, taking advantage of the economic boom occurring in Thailand with increased western investment due to its more stable, non-communist government and openness.

[citation needed] Around the 1990s, although the perceived political oppression continues and Thaification policies remain, attitudes towards regional languages relaxed.

Parents often view the language as a detriment to the betterment of their children, who must master Standard Thai to advance in school or career paths outside of agriculture.

[22][3] The written language is currently at Stage IX, which on the EGIDS scale is a 'language [that] serves as a reminder of heritage identity for an ethnic community, but no one has more than symbolic proficiency'.

Combined with vocabulary retentions, many of which sound oddly archaic or have become pejorative in Standard Thai, perpetuate the myth and negative perception of Isan as an uncouth language of rural poverty and hard agricultural life.

It is required to watch the ever-popular soap operas, news, and sports broadcasts or sing popular songs, most of it produced in Bangkok or at least in its accent.

Although attitudes towards regional cultures and languages began to relax in the late 1980s, the legal and social pressures of Thaification and the need for Thai to participate in daily life and wider society continue.

Digitizing palm-leaf manuscripts and providing Thai-script transcription is being conducted as a way to both preserve the rapidly decaying documents and re-introduce them to the public.

ຜ, ພ ຖ, ທ ຝ, ຟ ສ, ຊ ຣ8,11, ຫຼ4,8/ຫຣ4,8,11 Consonant clusters are rare in spoken Lao as they disappear shortly after the adoption of writing.

Of the consonant letters, excluding the disused ฃ and ฅ, six (ฉ ผ ฝ ห อ ฮ) cannot be used as a final and the other 36 are grouped as following.

Some words, mainly inherited from Sanskrit or Pali, have separate forms for male or female, such as thewa (Northeastern Thai: เทวา /tʰêː.wâː/, cf.

Compared to Thai, Isan and Lao frequently use the first- and second-person pronouns and rarely drop them in speech which can sometimes seem more formal and distant.

Unlike English, which indicates questions by a rising tone, or Spanish, which changes the order of the sentences to achieve the same result, Isan uses question-tag words.

Very quickly, the Isan people adopted an ad hoc system of using the Thai script to record the spoken Isan language, using etymological spelling for cognate words but spelling Lao words not found in Thai, and with no known Khmer or Indic etymology, similarly to as they would be in the Lao script.

The dynastic union allowed easy movement of monks from Lan Xang that came to copy the temple libraries to bring back home.

[35] Most of the script is recorded on palm-leaf manuscripts, many of which were destroyed during the 'Thaification' purges of the 1930s; contemporaneously this period of Thai nationalization also ended its use as the primary written language in Northern Thailand.