Islam in Turkey

The established presence of Islam in the region that now constitutes modern Turkey dates back to the later half of the 11th century, when the Seljuks started expanding into eastern Anatolia.

The Islamic Golden Age was soon inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad.

During the later fragmentation of the Abbasid rule and the rise of their Shiite rivals the Fatimids and Buyids, a resurgent Byzantium recaptured Crete and Cilicia in 961, Cyprus in 965, and pushed into the Levant by 975.

The Byzantines successfully contested with the Fatimids for influence in the region until the arrival of the Seljuk Turks who first allied with the Abbasids and then ruled as the de facto rulers.

In 1068, Alp Arslan and allied Turkoman tribes recaptured many Abbasid lands and even invaded Byzantine regions, pushing further into eastern and central Anatolia after a major victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

The conquest of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) in 1453 enabled the Ottomans to consolidate their empire in Anatolia and Thrace.

Early in the Ottoman period, the office of grand mufti of Istanbul evolved into that of Şeyhülislam (shaykh, or "leader of Islam"), which had ultimate jurisdiction over all the courts in the empire and consequently exercised authority over the interpretation and application of sharia.

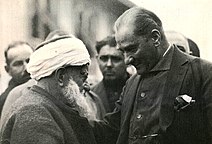

The withdrawal of Turkey, heir to the Ottoman Empire, as the presumptive leader of the international Muslim community, was symbolic of the change in the government's relationship to Islam.

Atatürk and his associates abolished certain religious practices and institutions and generally questioned the value of religion, preferring to place their trust in science.

When the reformers of the early 1920s opted for a secular state, they removed religion from the sphere of public policy and restricted it to exclusively that of personal morals, behavior, and faith.

These changes in devotional practices caused widespread criticism among Muslims, which led to a return to the Arabic version of the call to prayer in 1950, after the opposition party DP won the elections.

As early as 1925, religious grievances were one of the principal causes of the Şeyh Sait rebellion, an uprising in southeastern Turkey that may have claimed as many as 30,000 lives before being suppressed.

After 1950, some political leaders espoused support for programs and policies that appealed to the religiously inclined in an attempt to benefit from a lot of the population's attachment to religion.

This gradually led to a polarization of the entire country, which became especially evident in the 1980s, as a new generation of religiously motivated local leaders emerged to challenge the dominance of the secularized political elite.

By 1994, slogans promising that a return to Islam would cure economic ills and solve the problems of bureaucratic inefficiencies had enough general appeal to enable avowed religious candidates to win mayoral elections in Istanbul and Ankara.

Following the loosening of authoritarian political control in 1946, a large number of people began to openly call for a return to traditional religious practices.

Following the 1980 coup, the military, although secular in orientation, viewed religion as an effective means to counter socialist ideas and thus authorized the construction of 90 more İmam Hatip high schools.

According to the Hearth, Islam not only constitutes an essential aspect of Turkish culture, but is a force that can be regulated by the state to help socialize the people to be obedient citizens acquiescent to the overall secular order.

The result was a purge from these state institutions of more than 2,000 intellectuals perceived as espousing leftist ideas incompatible with the Hearth's vision of Turkey's national culture.

Prolific and popular writers such as Ali Bulaç, Rasim Özdenören, and İsmet Özel drew upon their knowledge of Western philosophy, Marxist sociology, and radical Islamist political theory to advocate for a modern Islamic perspective that does not hesitate to criticize societal issues while simultaneously remaining faithful to the ethical values and spiritual dimensions of religion.

On 15 July 2016, a coup d'état was attempted in Turkey against state institutions by a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces with connections to the Gülen movement, citing an erosion in secularism.

This state agency, established by Atatürk (1924), finance only Sunni Muslim worship Other religions must ensure a financially self-sustaining running and they face administrative obstacles during operation.

[20] The Diyanet is an official state institution established in 1924 and works to provide Quranic education for children, as well as drafting weekly sermons delivered to approximately 85,000 different mosques.

[35] Sufi orders like Alevi-Bektashi, Bayrami-Jelveti, Halveti (Gulshani, Jerrahi, Nasuhi, Rahmani, Sunbuli, Ussaki), Hurufi-Rüfai, Malamati, Mevlevi, Nakşibendi (Halidi, Haqqani), Qadiri-Galibi and Ja'fari Muslims[29] are not officially recognized.

Others In terms of Ihsan: Although intellectual debates on the role of Islam attracted widespread interest, they did not provoke the kind of controversy that erupted over the issue of appropriate attire for Muslim women.

During the early 1980s, female college students who were determined to demonstrate their commitment to Islam began to cover their heads and necks with scarves and wear long, shape-concealing overcoats.

Militant secularists persuaded the Higher Education Council to issue a regulation in 1987 forbidding female university students to cover their heads in class.

Throughout the first half of the 1990s, highly educated, articulate but religiously pious women have appeared in public dressed in Islamic attire that conceals all but their faces and hands.

Veneration of saints (both male and female) and pilgrimages to their shrines and graves represent an important aspect of popular Islam in the country.

The Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) regularly criticizes and insults Quranists, gives them no recognition and calls them kafirs (disbelievers).

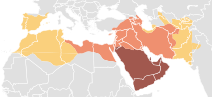

|

95–100%

|

|

|

90–95%

|

|

|

50–55%

|

|

|

30–35%

|

|

|

10–20%

|

|

|

5–10%

|

|

|

4–5%

|

|

|

2–4%

|

|

|

1–2%

|

|

|

< 1%

|