Islam in Albania

The post-communist period and the lifting of legal and other government restrictions on religion allowed Islam to revive through institutions that generated new infrastructure, literature, educational facilities, international transnational links and other social activities.

The demand for Muslim carpenters and blacksmiths to build war machines in Albania was so great during the summer of 1280 that it threatened to exhaust the skilled workers' pool for the construction of forts on the Italian coast.

[16][17] This practice has somewhat continued amongst Balkan Christian peoples in contemporary times who still refer to Muslim Albanians as Turks, Turco-Albanians, with often pejorative connotations and historic negative socio-political repercussions.

[15][23] Another factor overlaying these concerns during the Albanian National Awakening (Rilindja) period were thoughts that Western powers would only favour Christian Balkan states and peoples in the anti Ottoman struggle.

[29] There were intervening areas where Muslims lived alongside Albanian speaking Christians in mixed villages, towns and cities with either community forming a majority or minority of the population.

[58] Of the Muslim Albanian population, the Italians attempted to gain their sympathies by proposing to build a large mosque in Rome, though the Vatican opposed this measure and nothing came of it in the end.

[61] Within this context, religions like Islam were denounced as foreign and clergy such as Muslim muftis were criticised as being socially backward with the propensity to become agents of other states and undermine Albanian interests.

[65][66] The Muslim Sunni and Bektashi clergy alongside their Catholic and Orthodox counterparts suffered severe persecution and to prevent a decentralisation of authority in Albania, many of their leaders were killed.

[72] Following the wider trends for socio-political pluralism and freedom in Eastern Europe from communism, a series of fierce protests by Albanian society culminated with the communist regime collapsing after allowing two elections in 1991 and then 1992.

[66][84] Hafiz Sabri Koçi, (1921–2004) an imam imprisoned by the communist regime and who led the first prayer service in Shkodër 1990 became the grand mufti of the Muslim Community of Albania.

[89][99] In a post-communist environment the Muslim Community of Albania has been seeking from successive Albanian governments a return and restitution of properties and land confiscated by the communist regime though without much progress.

[100] the rest of Sufi orders are present in Albania such as the Rifais, Saidis, Halvetis, Qadiris and the Tijaniyah are Sunni and combined have 384 turbes, tekes, maqams and zawiyas.

[74][102] Bektashis also use Shiite related iconography of Ali, the Battle of Karbala and other revered Muslim figures of Muhammad's family that adorn the interiors of turbes and tekkes.

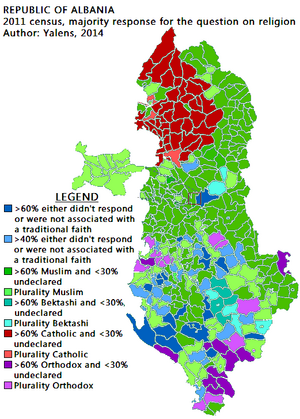

In the 2011 census the declared religious affiliation of the population was: 56.70% (1,587,608) Sunni Muslims, 2.09% (58,628) Bektashis, 10.03% (280,921) Catholics, 6.75% (188,992) Orthodox, 0.14% (3,797) Evangelists, 0.07% (1,919) other Christians, 5.49% (153,630) believers without denomination, 2.05% (69,995) Atheists, 13.79% (386,024) undeclared.

[66][108] The Romani community is often economically disadvantaged with at times facing socio-political discrimination and distance from wider Albanian society like for example little intermarriage or neighbourhood segregation.

In the north-eastern borderland region of Gorë, the Gorani community inhabits the villages of Zapod, Pakisht, Orçikël, Kosharisht, Cernalevë, Orgjost, Orshekë, Borje, Novosej and Shishtavec.

[127] During the Albanian socio-political and economic crisis of 1997, religious differences did not play a role in the civil unrest that occurred, though the Orthodox Church in Albania at the time privately supported the downfall of the Berisha government made up mainly of Muslims.

[74][121][131][132] Some other Muslim Albanians when emigrating have also converted to Catholicism and conversions in general to Christianity within Albania are associated with belonging and interpreted as being part of the West, its values and culture.

[87][124][135] In a Pew research centre survey of Muslim Albanians in 2012, religion was important for only 15%, while 7% prayed, around 5% went to a mosque, 43% gave zakat (alms), 44% fasted during Ramadan and 72% expressed a belief in God and Muhammad.

[138] Although considered a "national myth" by some,[139] the "Albanian example" of interfaith tolerance and of tolerant laicism[140] has been advocated as a model for the rest of the world by both Albanians and Western European and American commentators,[141][142] including Pope Francis who praised Albania as a "model for a world witnessing conflict in God's name"[143] and Prime Minister Edi Rama, who marched with Christian and Muslim clergy on either side in a demonstration in response to religious motivated violence in Paris.

[155] In Albania Halal slaughter of animals and food is permitted, mainly available in the eateries of large urban centres and becoming popular among people who are practicing Sunni Muslims.

[159][160] Prominent in those discussions were written exchanges in newspaper articles and books between novelist Ismail Kadare of Gjirokastër and literary critic Rexhep Qosja, an Albanian from Kosovo in the mid-2000s.

[161][162] In a 2005 speech given in Britain by president Alfred Moisiu of Orthodox heritage, he referred to Islam in Albania as having a "European face", it being "shallow" and that "if you dig a bit in every Albanian, he can discover his Christian core".

[163] Following trends dating back from the Communist regime, the post-Communist Albanian political establishment continues to approach Islam as the faith of the Ottoman invader.

Other debates, often in the media and occasionally heated, have been about public displays of Muslim practices, mosque construction in Albania, or local and international violent incidents and their relationship to Islam.

[168] Issues have also arisen over school textbooks and their inaccurate references of Islam such as describing Muhammad as God's "son", while other matters have been concerns over administrative delays for mosque construction and so on.

Both Catholic and the Orthodox clergy interpret the Ottoman era as a repressive one that contained anti-Christian discrimination and violence,[175] while Islam is viewed as foreign challenging Albanian tradition and cohesion.

[183] In the 1990s, small groups of militant Muslims took advantage of dysfunctional government, porous borders, corruption, weak laws and illegal activities occurring during Albania's transition to democracy.

[74] As of March 2016, some 100 or so Albanians so far have left Albania to become foreign fighters by joining various fundamentalist Salafi jihadist groups involved in the ongoing civil wars of Syria and Iraq; 18 have died.

[194] During the Kosovo War (1999) and ethnic cleansing of mostly Muslim Albanians by Orthodox Serbs alongside the subsequent refugee influx into the country, Albania's status as an ally of the US was confirmed.

|

95–100%

|

|

|

90–95%

|

|

|

50–55%

|

|

|

30–35%

|

|

|

10–20%

|

|

|

5–10%

|

|

|

4–5%

|

|

|

2–4%

|

|

|

1–2%

|

|

|

< 1%

|