Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world

A significant number of stars in the sky, such as Aldebaran, Altair and Deneb, and astronomical terms such as alidade, azimuth, and nadir, are still referred to by their Arabic names.

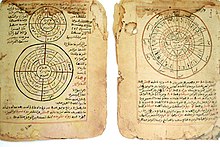

A large corpus of literature from Islamic astronomy remains today, numbering approximately 10,000 manuscripts scattered throughout the world, many of which have not been read or catalogued.

The Islamic historian Ahmad Dallal notes that, unlike the Babylonians, Greeks, and Indians, who had developed elaborate systems of mathematical astronomical study, the pre-Islamic Arabs relied upon empirical observations.

Fragments of texts during this period show that Arab astronomers adopted the sine function from India in place of the chords of arc used in Greek trigonometry.

[1] Ptolemy’s Almagest (a geocentric spherical Earth cosmic model) was translated at least five times in the late eighth and ninth centuries,[4] which was the main authoritative work that informed the Arabic astronomical tradition.

[5] The rise of Islam, with its obligation to determine the five daily prayer times and the qibla (the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca) inspired intellectual progress in astronomy.

[citation needed] The first major Muslim work of astronomy was Zij al-Sindhind, produced by the mathematician Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in 830.

[11] Islamic scholars questioned the Earth's apparent immobility,[12] and position at the centre of the universe, now that independent investigations into the Ptolemaic system were possible.

In 1070, Abu Ubayd al-Juzjani published the Tarik al-Aflak, in which he discussed the issues arising from Ptolemy's theory of equants, and proposed a solution.

The anonymous work al-Istidrak ala Batlamyus ("Recapitulation regarding Ptolemy"), produced in Al-Andalus, included a list of objections to Ptolemic astronomy.

He studied it in his youth, and in 1420 ordered the construction of Ulugh Beg Observatory, which produced a new set of astronomical tables, as well as contributing to other scientific and mathematical advances.

[26] In 1217, Michael Scot finished a Latin translation of al-Bitruji's Book of Cosmology (Kitāb al-Hayʾah), which became a valid alternative to Ptolemy's Almagest in scholasticist circles.

[26][29] Some historians maintain that the thought of the Maragheh observatory, in particular the mathematical devices known as the Urdi lemma and the Tusi couple, influenced Renaissance-era European astronomy and thus Copernicus.

It has been suggested[47][48] that the idea of the Tusi couple may have arrived in Europe leaving few manuscript traces, since it could have occurred without the translation of any Arabic text into Latin.

[53] Islamic influence on Chinese astronomy was first recorded during the Song dynasty when a Hui Muslim astronomer named Ma Yize introduced the concept of seven days in a week and made other contributions.

[54] Islamic astronomers were brought to China in order to work on calendar making and astronomy during the Mongol Empire and the succeeding Yuan dynasty.

[56] Several Chinese astronomers worked at the Maragheh observatory, founded by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in 1259 under the patronage of Hulagu Khan in Persia.

[60] While formulating the Shoushili calendar in 1281, Shoujing's work in spherical trigonometry may have also been partially influenced by Islamic mathematics, which was largely accepted at Kublai's court.

[61] These possible influences include a pseudo-geometrical method for converting between equatorial and ecliptic coordinates, the systematic use of decimals in the underlying parameters, and the application of cubic interpolation in the calculation of the irregularity in the planetary motions.

[60] Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368–1398) of the Ming dynasty (1328–1398), in the first year of his reign (1368), conscripted Han and non-Han astrology specialists from the astronomical institutions in Beijing of the former Mongolian Yuan to Nanjing to become officials of the newly established national observatory.

In order to enhance accuracy in methods of observation and computation, Hongwu Emperor reinforced the adoption of parallel calendar systems, the Han and the Hui.

The translation of two important works into Chinese was completed in 1383: Zij (1366) and al-Madkhal fi Sina'at Ahkam al-Nujum, Introduction to Astrology (1004).

During the 10th century, the Buwayhid dynasty encouraged the undertaking of extensive works in astronomy; such as the construction of a large-scale instruments with which observations were made in the year 950.

In 1420, prince Ulugh Beg, himself an astronomer and mathematician, founded another large observatory in Samarkand, the remains of which were excavated in 1908 by Russian teams.

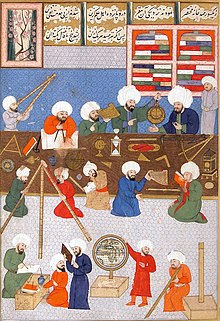

And finally, Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf founded a large observatory in Ottoman Constantinople in 1577, which was on the same scale as those in Maragha and Samarkand.

[70] The device was incredibly useful, and sometime during the 10th century it was brought to Europe from the Muslim world, where it inspired Latin scholars to take up an interest in both math and astronomy.

[71][failed verification] The largest function of the astrolabe is it serves as a portable model of space that can calculate the approximate location of any heavenly body found within the solar system at any point in time, provided the latitude of the observer is accounted for.

[77] Abu Rayhan Biruni designed an instrument he called "Box of the Moon", which was a mechanical lunisolar calendar, employing a gear train and eight gear-wheels.

[87] The desert castle at Qasr Amra, which was used as a Umayyad palace, has a bath dome decorated with the Islamic zodiac and other celestial designs.

Ewers depicting the twelve zodiac symbols exist in order to emphasize elite craftsmanship and carry blessings such as one example now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.