Equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets.

The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the planetary orbit.

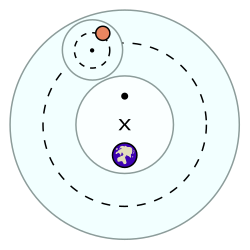

[1] The equant point (shown in the diagram by the large • ), is placed so that it is directly opposite to Earth from the deferent's center, known as the eccentric (represented by the × ).

To a hypothetical observer placed at the equant point, the epicycle's center (indicated by the small · ) would appear to move at a steady angular speed.

[2] The reason for the implementation of the equant was to maintain a semblance of constant circular motion of celestial bodies, a long-standing article of faith originated by Aristotle for philosophical reasons, while also allowing for the best match of the computations of the observed movements of the bodies, particularly in the size of the apparent retrograde motion of all Solar System bodies except the Sun and the Moon.

The moving object's speed will vary during its orbit around the outer circle (dashed line), faster in the bottom half and slower in the top half, but the motion is considered uniform because the planet goes through equal angles in equal times from the perspective of the equant point.

Applied without an epicycle (as for the Sun), using an equant allows for the angular speed to be correct at perigee and apogee, with a ratio of

[2] In models of planetary motion that precede Ptolemy, generally attributed to Hipparchus, the eccentric and epicycles were already a feature.

Before around the year 430 BCE, Meton and Euktemon of Athens observed differences in the lengths of the seasons.

[2] This can be observed in the lengths of seasons, given by equinoxes and solstices that indicate when the Sun traveled 90 degrees along its path.

According to these calculations, Spring lasted about 94+1/ 2 days, Summer about 92+1/ 2 , Fall about 88+1/ 8 , and Winter about 90+1/ 8 , showing that seasons did indeed have differences in lengths.

This was true specifically regarding the actual spacing and widths of retrograde arcs, which could be seen later according to Ptolemy's model and compared.

He did this without much explanation or justification for how he arrived at the point of its creation, deciding only to present it formally and concisely with proofs as with any scientific publication.

[2] Ptolemy's model of astronomy was used as a technical method that could answer questions regarding astrology and predicting planets positions for almost 1,500 years, even though the equant and eccentric were regarded by many later astronomers as violations of pure Aristotelian physics which presumed all motion to be centered on the Earth.

[2] For many centuries rectifying these violations was a preoccupation among scholars, culminating in the solutions of Ibn al-Shatir and Copernicus.

Ptolemy's predictions, which required constant review and corrections by concerned scholars over those centuries, culminated in the observations of Tycho Brahe at Uraniborg.

Noted critics of the equant include the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din Tusi who developed the Tusi couple as an alternative explanation,[10] and Nicolaus Copernicus, whose alternative was a new pair of small epicycles for each deferent.

[11][12] The violation of uniform circular motion around the center of the deferent bothered many thinkers, especially Copernicus, who mentions the equant as a "monstrous construction" in De Revolutionibus.