Islamic ornament

[1][2] This aniconism in Islamic culture encouraged artists to explore non-figural art, creating a general aesthetic shift toward mathematically-based decoration.

As early as the fourth century, Byzantine architecture showcased influential forms of abstract ornament in stonework.

"[11] Wade argues that the aim is to transfigure, turning mosques "into lightness and pattern", while "the decorated pages of a Qur’an can become windows onto the infinite.

She argues that beauty, whether in poetry or in the visual arts, was enjoyed "for its own sake, without commitment to religious or moral criteria".

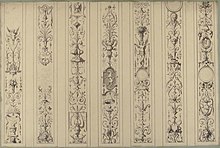

[12] The Islamic arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines,[13] often combined with other elements.

[14] This technique, which emerged thanks to artistic interest in older geometric compositions in Late Antique art, made it possible for the viewer to imagine what the pattern would look like if it continued beyond its actual limits.

[15] The vegetal forms commonly used within the patterns, such as acanthus leaves, grapes, and more abstract palmettes, were initially derived from Late Antique and Sasanian art.

These may constitute the entire decoration, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the background around other motifs.

[4][20][5][21] Geometric forms such as circles, squares, rhombs, dodecagons, and stars vary in their representation and configuration across the world of Islam.

Geometric patterns occur in a variety of forms in Islamic art and architecture including kilim carpets,[22] Persian girih[23] and western zellij tilework,[24][25] muqarnas decorative vaulting,[26] jali pierced stone screens,[27] ceramics,[28] leather,[29] stained glass,[30][31] woodwork,[32] and metalwork.

[35] The importance of the written word in Islam ensured that epigraphic or calligraphic decoration played a prominent role in architecture.

[36] Calligraphy is used to ornament buildings such as mosques, madrasas, and mausoleums; wooden objects such as caskets; and ceramics such as tiles and bowls.

[39] For example, the calligraphic inscriptions adorning the Dome of the Rock include quotations from the Qur'an that reference the miracle of Jesus and his human nature (e.g. Quran 19:33–35), the oneness of God (e.g. Qur'an 112), and the role of Muhammad as the "Seal of the Prophets", which have been interpreted as an attempt to announce the rejection of the Christian concept of the Holy Trinity and to proclaim the triumph of Islam over Christianity and Judaism.

[40][41][42] Additionally, foundation inscriptions on buildings commonly indicate its founder or patron, the date of its construction, the name of the reigning sovereign, and other information.

[36] The earliest examples of epigraphic inscriptions in Islamic art demonstrate a more unplanned approach in which calligraphy is not integrated with other decoration.

Theories on ornament can be located in the writings of Alois Reigl, William Morris, John Ruskin, Carl Semper, and Viollet-le-Duc.

The richly textured geometric forms in the Alhambra function as a passageway, an essence, for viewers to meditate on life and afterlife.