Islamic geometric patterns

These include kilim carpets, Persian girih and Moroccan zellij tilework, muqarnas decorative vaulting, jali pierced stone screens, ceramics, leather, stained glass, woodwork, and metalwork.

Interest in Islamic geometric patterns is increasing in the West, both among craftsmen and artists like M. C. Escher in the twentieth century, and among mathematicians and physicists such as Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt.

[1][2] From the 9th century onward, a range of sophisticated geometric patterns based on polygonal tessellation began to appear in Islamic art, eventually becoming dominant.

[4][5] This aniconism in Islamic culture caused artists to explore non-figural art, and created a general aesthetic shift toward mathematically based decoration.

"[10] Wade argues that the aim is to transfigure, turning mosques "into lightness and pattern", while "the decorated pages of a Qur’an can become windows onto the infinite.

[11] Many Islamic designs are built on squares and circles, typically repeated, overlapped and interlaced to form intricate and complex patterns.

[19][20][21] The mathematical properties of the decorative tile and stucco patterns of the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain have been extensively studied.

[25] The next development, marking the middle stage of Islamic geometric pattern usage, was of 6- and 8-point stars, which appear in 879 at the Ibn Tulun Mosque, Cairo, and then became widespread.

Abstract 6- and 8-point shapes appear in the Tower of Kharaqan at Qazvin, Persia in 1067, and the Al-Juyushi Mosque, Egypt in 1085, again becoming widespread from there, though 6-point patterns are rare in Turkey.

[25] Finally, marking the end of the middle stage, 8- and 12-point girih rosette patterns appear in the Alâeddin Mosque at Konya, Turkey in 1220, and in the Abbasid palace in Baghdad in 1230, going on to become widespread across the Islamic world.

[25] The beginning of the late stage is marked by the use of simple 16-point patterns at the Hasan Sadaqah mausoleum in Cairo in 1321, and in the Alhambra in Spain in 1338–1390.

These include ceramics,[27] girih strapwork,[28] jali pierced stone screens,[29] kilim rugs,[30] leather,[31] metalwork,[32] muqarnas vaulting,[33] shakaba stained glass,[34] woodwork,[28] and zellij tiling.

[27] Thus an unglazed earthenware water flask[e] from Aleppo in the shape of a vertical circle (with handles and neck above) is decorated with a ring of moulded braiding around an Arabic inscription with a small 8-petalled flower at the centre.

[28] Girih designs are traditionally made in different media including cut brickwork, stucco, and mosaic faience tilework.

Most designs are based on a partially hidden geometric grid which provides a regular array of points; this is made into a pattern using 2-, 3-, 4-, and 6-fold rotational symmetries which can fill the plane.

The visible pattern superimposed on the grid is also geometric, with 6-, 8-, 10- and 12-pointed stars and a variety of convex polygons, joined by straps which typically seem to weave over and under each other.

Modern, simplified jali walls, for example made with pre-moulded clay or cement blocks, have been popularised by the architect Laurie Baker.

Because weaving uses vertical and horizontal threads, curves are difficult to generate, and patterns are accordingly formed mainly with straight edges.

[34][47] Traditions of stained glass set in wooden frames (not lead as in Europe) survive in workshops in Iran as well as Azerbaijan.

[48] Glazed windows set in stucco arranged in girih-like patterns are found both in Turkey and the Arab lands; a late example, without the traditional balance of design elements, was made in Tunisia for the International Colonial Exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883.

[50] Zellij (Arabic: الزَّلِيْج) is geometric tilework with glazed terracotta tiles set into plaster, forming colourful mosaic patterns including regular and semiregular tessellations.

[35] It is sometimes supposed in Western society that mistakes in repetitive Islamic patterns such as those on carpets were intentionally introduced as a show of humility by artists who believed only Allah can produce perfection, but this theory is denied.

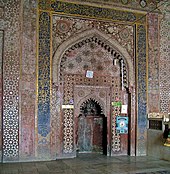

[55] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has among other relevant holdings 124 mediaeval (1000–1400 A.D.) objects bearing Islamic geometric patterns,[56] including a pair of Egyptian minbar (pulpit) doors almost 2 m. high in rosewood and mulberry inlaid with ivory and ebony;[57] and an entire mihrab (prayer niche) from Isfahan, decorated with polychrome mosaic, and weighing over 2,000 kg.

[58] Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a significant influence on Western art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types back to Italy from the 14th century onwards.

The panel included the experts on Islamic geometric pattern Carol Bier,[g] Jay Bonner,[h][66] Eric Broug,[i] Hacali Necefoğlu[j] and Reza Sarhangi.

[72] Two physicists, Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt, attracted controversy in 2007 by claiming[73] that girih designs such as that used on the Darb-e Imam shrine[l] in Isfahan were able to create quasi-periodic tilings resembling those discovered by Roger Penrose in 1973.

[74] In 2016, Ahmad Rafsanjani described the use of Islamic geometric patterns from tomb towers in Iran to create auxetic materials from perforated rubber sheets.