Isoperimetric inequality

The isoperimetric problem is to determine a plane figure of the largest possible area whose boundary has a specified length.

The isoperimetric problem has been extended in multiple ways, for example, to curves on surfaces and to regions in higher-dimensional spaces.

Perhaps the most familiar physical manifestation of the 3-dimensional isoperimetric inequality is the shape of a drop of water.

[citation needed] The 15th-century philosopher and scientist, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa, considered rotational action, the process by which a circle is generated, to be the most direct reflection, in the realm of sensory impressions, of the process by which the universe is created.

German astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler invoked the isoperimetric principle in discussing the morphology of the solar system, in Mysterium Cosmographicum (The Sacred Mystery of the Cosmos, 1596).

Although the circle appears to be an obvious solution to the problem, proving this fact is rather difficult.

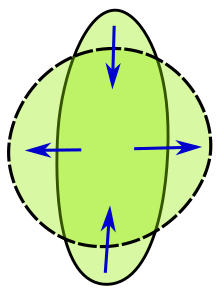

Steiner begins with some geometric constructions which are easily understood; for example, it can be shown that any closed curve enclosing a region that is not fully convex can be modified to enclose more area, by "flipping" the concave areas so that they become convex.

It can further be shown that any closed curve which is not fully symmetrical can be "tilted" so that it encloses more area.

The one shape that is perfectly convex and symmetrical is the circle, although this, in itself, does not represent a rigorous proof of the isoperimetric theorem (see external links).

The solution to the isoperimetric problem is usually expressed in the form of an inequality that relates the length L of a closed curve and the area A of the planar region that it encloses.

The area of a disk of radius R is πR2 and the circumference of the circle is 2πR, so both sides of the inequality are equal to 4π2R2 in this case.

In 1902, Hurwitz published a short proof using the Fourier series that applies to arbitrary rectifiable curves (not assumed to be smooth).

An elegant direct proof based on comparison of a smooth simple closed curve with an appropriate circle was given by E. Schmidt in 1938.

It uses only the arc length formula, expression for the area of a plane region from Green's theorem, and the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

For a given closed curve, the isoperimetric quotient is defined as the ratio of its area and that of the circle having the same perimeter.

Denote by L the length of C and by A the area enclosed by C. The spherical isoperimetric inequality states that and that the equality holds if and only if the curve is a circle.

There are, in fact, two ways to measure the spherical area enclosed by a simple closed curve, but the inequality is symmetric with the respect to taking the complement.

This inequality was discovered by Paul Lévy (1919) who also extended it to higher dimensions and general surfaces.

[5] In the more general case of arbitrary radius R, it is known[6] that The isoperimetric inequality states that a sphere has the smallest surface area per given volume.

Under additional restrictions on the set (such as convexity, regularity, smooth boundary), the equality holds for a ball only.

An extremal set consists of a ball and a "corona" that contributes neither to the volume nor to the surface area.

is the (n-1)-dimensional Minkowski content, Ln is the n-dimensional Lebesgue measure, and ωn is the volume of the unit ball in

In 1970's and early 80's, Thierry Aubin, Misha Gromov, Yuri Burago, and Viktor Zalgaller conjectured that the Euclidean isoperimetric inequality holds for bounded sets

In dimensions 3 and 4 the conjecture was proved by Bruce Kleiner in 1992, and Chris Croke in 1984 respectively.

Most of the work on isoperimetric problem has been done in the context of smooth regions in Euclidean spaces, or more generally, in Riemannian manifolds.

However, the isoperimetric problem can be formulated in much greater generality, using the notion of Minkowski content.

If X is the Euclidean plane with the usual distance and the Lebesgue measure then this question generalizes the classical isoperimetric problem to planar regions whose boundary is not necessarily smooth, although the answer turns out to be the same.

Isoperimetric profiles have been studied for Cayley graphs of discrete groups and for special classes of Riemannian manifolds (where usually only regions A with regular boundary are considered).

[7] Isoperimetric inequalities for graphs relate the size of vertex subsets to the size of their boundary, which is usually measured by the number of edges leaving the subset (edge expansion) or by the number of neighbouring vertices (vertex expansion).

Harper's theorem[10] says that Hamming balls have the smallest vertex boundary among all sets of a given size.