Israeli citizenship law

The dissolution of the mandate in 1948 and subsequent conflict created a set of complex citizenship circumstances for the non-Jewish inhabitants of the region that continue to be unresolved.

[8] The area nominally remained an Ottoman territory following the conclusion of the war until the United Kingdom obtained a League of Nations mandate for the region in 1922.

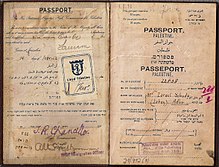

Similarly, local residents ostensibly continued their status as Ottoman subjects, although British authorities began issuing provisional certificates of Palestinian nationality shortly after the start of occupation.

[9] The terms of the mandate allowed Britain to exclude its application on certain parts of the region; this exclusion was exercised on the territory east of the Jordan River,[10] where the Emirate of Transjordan was established.

[13] Turkish nationals originating from Mandate territory but habitually resident elsewhere on 6 August 1924 had a right to choose Palestinian citizenship, but this required an application within two years of the treaty's enforcement and approval by the Mandatory government.

[19] However, despite Israel's status as the successor state to Mandatory Palestine,[20] Israeli courts during this time offered conflicting opinions on the continuing validity of Palestinian citizenship legislation enacted during the British mandate.

[21] While almost all courts held that Palestinian citizenship had ceased to exist at the end of the mandate in 1948 without a replacement status, there was one case in which a judge ruled that all residents of Palestine at the time of Israel's establishment were automatically Israeli nationals.

A 1960 Supreme Court ruling partially addressed this by allowing a looser interpretation of the residential requirements; individuals who had permission to temporarily leave Israel during or shortly after the conflict qualified for citizenship, despite their gap in residence.

[45] Government and religious authorities continually disagreed over the meaning of the word and its application to that law, with some organizations considering the Jewish religion and nationality to be the same concept.

[48] The Law of Return was amended in 1970 to provide a more detailed explanation of who qualifies: a Jew means any person born to a Jewish mother, or someone who has converted to Judaism and is not an adherent of another religion.

This change was made to facilitate emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union, who were routinely denied exit visas,[51] especially after the 1967 Six-Day War.

[53][54] However, these countries soon imposed restrictions on Jews who could immigrate from the Soviet Union at the request of the Israeli government, which intended to redirect the flow of migrants to Israel itself.

[56] Most of this wave of migrants were nonpracticing and secular Jews; a significant portion were not considered Jewish under halakha, but qualified for immigration based on the Law of Return.

[58] The Chief Rabbinate operates under an Orthodox interpretation of halakha and is the authoritative institution for religious matters within Israel, which has led to disputes over whether converts into non-Orthodox movements of Judaism should be recognized as Jews.

[60] Both the Chief Rabbinate and Supreme Court consider followers of Messianic Judaism as Christians and specifically bar them from right of return,[61] unless they otherwise have sufficient Jewish descent.

[62] Ethiopian Jews, also known as Beta Israel, lived as an isolated community away from mainstream Judaism since at least the Early Middle Ages prior to their contact with the outside world in the 19th century.

Over the course of their prolonged separation, this population developed a number of religious practices heavily influenced by Coptic Christianity differing from those of other Jews.

[64] Following Ethiopia's communist revolution and the subsequent outbreak of civil war, the Israeli government resettled 45,000 people, nearly the entire Ethiopian Jewish population.

A ministerial decision in 1992 ruled this community ineligible for right of return, but some migrants were allowed to immigrate to Israel for family reunification.

[69] In 1949, the Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett declared Samaritans eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return, reasoning that their Hebrew heritage qualified them for recognition as Jews.

The Supreme Court ruled on the matter in 1994, restoring the original policy and further extending Samaritan eligibility for citizenship to members of the group who reside in the West Bank.

[73] Individuals born in Israel who are between the ages of 18 and 21 and have never held any nationality are entitled to citizenship, provided they have been continuously resident for the five years immediately preceding their application.

Candidates must be physically present in the country at the time of application, be able to demonstrate knowledge of the Hebrew language, have the intention of permanently settling in Israel, and renounce any foreign nationalities.

Persons opting to naturalize are typically individuals who migrate to Israel for employment or family reasons, or are permanent residents of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

[83] Returnees living in Israel who obtained Israeli citizenship may voluntarily renounce that status if continuing to hold it would cause their loss of another country's nationality.

While some former citizens renounce their citizenship because of their intention to permanently settle overseas and not return to Israel, others do so as a condition of obtaining foreign nationality in their country of residence.

Common-law or same-sex partners are subject to a longer 7.5-year gradual process that grants permanent residency, after which they may apply for naturalization under the standard procedure.

[94] The 2003 Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law effectively discouraged further marriages between Israeli citizens and Palestinians by adding cumbersome administrative barriers that made legal cohabitation prohibitively difficult for affected couples.

Affected persons are only allowed to remain in Israel on temporary permits, which would lapse on the death of their spouses or if they were to fail to receive regular reapproval by the Israeli government.

[96] These restrictions were challenged as unconstitutional for violating the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty on the basis that the legislation was discriminatory by disproportionally affecting Israeli citizens who were ethnically Arab.