Italian Eritrea

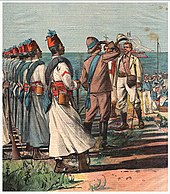

Occupation of Massawa in 1885 and the subsequent expansion of territory would gradually engulf the region and in 1889 the Ethiopian Empire recognized the Italian possession in the Treaty of Wuchale.

As the Suez Canal neared completion, he began to visualize the establishment of a coaling station and port of call for Italian steamships in the Red Sea.

Sapeto won over the Italian minister for foreign affairs, and King Victor Emmanuel II, to whom he explained his ideas.

Meanwhile, the government had been in touch with Raffaele Rubattino, whose company was planning to establish a steamship line through the newly opened Suez Canal and the Red Sea to India.

In 1884, the British Hewett Treaty promised the Bogos—the highlands of modern Eritrea—and free access to the Massawan coast to Emperor Yohannes IV in exchange for his help evacuating garrisons from the Sudan;[4] In the vacuum left by the Egyptian withdrawal, though, British diplomats were concerned about the rapid expansion of French Somaliland, France's colony along the Gulf of Tadjoura.

Located on a coral island[5] surrounded by lucrative pearl-fishing grounds,[6] the superior port was fortified and made the capital of the Italian governor.

[7] As they were not a party to the Hewett Treaty, the Italians began restricting access to arms shipments and imposing customs duties on Ethiopian goods immediately.

In the disorder that followed the 1889 death of Yohannes IV, Gen. Oreste Baratieri occupied the highlands along the Eritrean coast and Italy proclaimed the establishment of a new colony of Eritrea (from the Latin name for the Red Sea), with capital Asmara in substitution of Massawa.

Uccialli) signed the same year, King Menelik of Shewa—a southern Ethiopian kingdom—recognized the Italian occupation of his rivals' lands of Bogos, Hamasien, Akele Guzay, and Serae in exchange for guarantees of financial assistance and continuing access to European arms and ammunition.

His subsequent victory over his rival kings and enthronement as Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913) made the treaty formally binding upon the entire country.

Once established, however, Menelik took a dim view towards Italian involvement with local leaders in his northern province of Tigray;[8] while the Italians, for their part, felt bound to involvement given the regular Tigrayan raiding of tribes within their colony's protectorate[6] and the Tigrayan leaders themselves continued to claim the provinces now held by Italy.

Secure both domestically and militarily (thanks to arms shipments via French Djibouti and Harar), Menelik denounced the treaty in whole and the ensuing war, culminating in Italy's disastrous defeat at Adwa, ended their hopes of annexing Ethiopia for a time.

In a region marked by cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity, a succession of Italian governors maintained a notable degree of unity and public order.

The newly opened factories produced buttons, cooking oil, and pasta, construction materials, packing meat, tobacco, hide and other household commodities.

[22] Furthermore, after World War I, service with the Ascari become the main source of paid employment for the indigenous male population of Italian Eritrea.

Features include designated city zoning and planning, wide treed boulevards, political areas and districts and space and scope for development.

The city has been regarded as "New Rome" due to its quintessential Italian touch, not only for the architecture but also for the wide streets, piazzas and coffee bars.

While the boulevards are lined with palms and indigenous shiba'kha trees, there are numerable pizzerias and coffee bars, serving cappuccinos and lattes, as well as ice cream parlours.

[26] When the Allies captured Italian-held Eritrea in January 1941, most of the infrastructure and the industrial areas were extremely damaged and the remaining ones (like the Asmara-Massawa Cableway) were successively removed and sent to India and Kenya as war reparations.