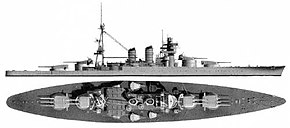

Italian battleship Giulio Cesare

Giulio Cesare was one of three Conte di Cavour-class dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina) in the 1910s.

During World War II, both Giulio Cesare and her sister ship, Conte di Cavour, participated in the Battle of Calabria in July 1940, when the former was lightly damaged.

The ships carried enough coal and oil[4] to give them a range of 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

For defense against torpedo boats, the ships carried fourteen 76.2-millimeter (3 in) guns; thirteen of these could be mounted on the turret tops, but they could be positioned in 30 different locations, including some on the forecastle and upper decks.

In 1925–1926 the foremast was replaced by a four-legged (tetrapodal) mast, which was moved forward of the funnels,[9] the rangefinders were upgraded, and the ship was equipped to handle a Macchi M.18 seaplane mounted on the amidships turret.

On her sea trials in December 1936, before her reconstruction was fully completed, Giulio Cesare reached a speed of 28.24 knots (52.30 km/h; 32.50 mph) from 93,430 shp (69,670 kW).

[18] Atop the conning tower there was a fire-control director fitted with two large stereo-rangefinders, with a base length of 7.2 meters (23.6 ft).

A major problem of the reconstruction was that the ship's increased draft meant that their waterline armor belt was almost completely submerged with any significant load.

[9] Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, the Italian naval chief of staff, believed that Austro-Hungarian submarines and minelayers could operate too effectively in the narrow waters of the Adriatic.

[22] Instead, Revel decided to implement a blockade at the relatively safer southern end of the Adriatic with the battle fleet, while smaller vessels, such as the MAS torpedo boats, conducted raids on Austro-Hungarian ships and installations.

Meanwhile, Revel's battleships would be preserved to confront the Austro-Hungarian battle fleet in the event that it sought a decisive engagement.

Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, attempted to interpose his ships between the Italians and their base at Taranto.

Three minutes after she opened fire, shells from Giulio Cesare began to straddle Warspite which made a small turn and increased speed, to throw off the Italian ship's aim, at 16:00.

Some rounds fired by Giulio Cesare overshot Warspite and near-missed the destroyers HMS Decoy and Hereward, puncturing their superstructures with splinters.

Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they successfully disengaged.

[26] On the night of 11 November 1940, Giulio Cesare and the other Italian battleships were at anchor in Taranto harbor when they were attacked by 21 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers from the British aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, along with several other warships.

On 8 February, she sailed from to the Straits of Bonifacio to intercept what the Italians thought was a Malta convoy, but was actually a raid on Genoa.

[29] After the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, she steamed to Taranto, putting down a mutiny and enduring an ineffective attack by five German aircraft en route.

The ship was stricken from the naval register on 15 December and turned over to the Soviets on 6 February 1949 under the temporary name of Z11 in Vlorë, Albania.

This was intended as a temporary rearmament, as the Soviets drew up plans to replace her secondary 120mm mounts with the 130mm/58 SM-2 that was in development, and the 100mm and 37mm guns with 8 quadruple 45mm.

[33] While at anchor in Sevastopol on the night of 28/29 October 1955, an explosion ripped a 4-by-14-meter (13 by 46 ft) hole in the forecastle forward of 'A' turret.

The official cause, regarded as the most probable, was a magnetic RMH or LMB bottom mine, laid by the Germans during World War II and triggered by the dragging of the battleship's anchor chain before mooring for the last time.