Italian resistance movement

[1] The Italian Resistance has its roots in anti-fascism, which progressively developed in the period from the mid-1920s, when weak forms of opposition to the fascist regime already existed, until the beginning of World War II.

[4] The Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy (PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization.

[8] After the murder of the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti (1924) and the decisive assumption of responsibility by Mussolini, the process of totalitarianization of the State began in the Kingdom of Italy, which will give rise to ever greater control and severe persecution of opponents, at risk of imprisonment and confinement.

Their activity was limited to the ideological side; the production of writings was copious, particularly among the anti-fascist exile communities, which however did not reach the masses and did not influence public opinion.

[17] Many Italian anti-fascists participated in the Spanish Civil War with the hope of setting an example of armed resistance to Franco's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".

[19] Outnumbered German Fallschirmjäger and Panzergrenadiere were initially repelled and endured losses, but slowly gained the upper hand, aided by their experience and superior Panzer component.

The defenders were hampered by a number of facts: Allied support was cancelled at the last minute since the Fallschirmjäger took the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division drop zones (Brigadier General Maxwell D. Taylor had crossed enemy lines and gone to Rome to personally supervise the operation); King Victor Emmanuel III, Marshal Pietro Badoglio and their staff fled to Brindisi, which left the generals in charge of the city without a coordinated defence plan; [20] also the absence of the Italian Centauro II Division, composed primarily of ex-Blackshirts and not trusted, with its German-made tanks, contributed to the defeat of the Italian forces by the Germans.

[22] On 10 September 1943, during Operation Achse, a small German flotilla, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Karl-Wolf Albrand, tried to enter the harbour of Piombino but was denied access by the port authorities.

[22][23][24] This however did not stop the protests; some junior officers, acting on their own initiative and against the orders (Perni and De Vecchi even tried to dismiss them for this), assumed command and started distributing weapons to the population, and civilian volunteers joined the Italian sailors and soldiers in the defense.

In the days following 8 September 1943 most servicemen, left without orders from higher echelons (due to Wehrmacht units ceasing Italian radio communications), were disarmed and shipped to POW camps in the Third Reich (often by smaller German outfits).

With reinforcements from SAS, SBS and British Army troops under the command of Generals Francis Gerrard Russell Brittorous and Robert Tilney, the defenders held on for a month.

On 1 March 2001, the President of the Italian Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi visited Cefalonia, giving a speech underlining how "their conscious choice [of the Acqui Division] was the first act of the Resistenza, of an Italy free from fascism".

Elsewhere, the nascent movement began as independently operating groups were organized and led by previously outlawed political parties or by former officers of the Royal Italian Army.

[42] A further challenge to the 'national unity' embodied in the CLN came from anarchists as well as dissident-communist Resistance formations, such as Turin's Stella Rossa movement and the Movimento Comunista d'Italia (Rome's largest single anti-fascist force under Occupation), which sought a revolutionary outcome to the conflict and were thus unwilling to collaborate with 'bourgeois parties'.

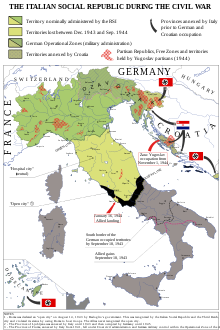

[44] On 15 June 1944, the General Staff of the Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano estimated that the partisan forces amounted to some 82,000 men, of whom about 25,000 operated in Piedmont, 14,200 in Liguria, 16,000 in the Julian March, 17,000 in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, 5,600 in Veneto, and 5,000 in Lombardy.

[46] Their ranks were gradually increased by the influx of young men escaping the Italian Social Republic's draft, as well as from deserters from the RSI armed forces.

An intelligence officer told Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Germany's commander of occupation forces in Italy, that he estimated German casualties fighting partisans in the summer of 1944 amounted to 30,000 to 35,000, including 5,000 confirmed killed.

In their attempts to suppress the resistance, German and Italian Fascist forces (especially the SS, Gestapo, and paramilitary militias such as Xª MAS and Black Brigades) committed war crimes, including summary executions and systematic reprisals against the civilian population.

[62] Although other European countries such as Norway, the Netherlands, and France also had partisan movements and collaborationist governments with Nazi Germany, armed confrontation between compatriots was more intense in Italy, making the Italian case unique.

Some later became well-known, such as climber and explorer Bill Tilman, reporter and historian Peter Tompkins, former RAF pilot Count Manfred Beckett Czernin, and architect Oliver Churchill.

[69] Another task carried out by the resistance was assisting escaping POWs (an estimated 80,000 were interned in Italy until 8 September 1943),[70] to reach Allied lines or Switzerland on paths previously used by smugglers.

DELASEM operated in Rome until the liberation under the leadership of the Jewish delegates Septimius Sorani, Giuseppe Levi, and the Capuchin Father Maria Benedetto.

[72] Given the revolutionary dimension of the insurrection in the industrial centres of Turin, Milan, and Genoa, where concerted factory occupations by armed workers had occurred, the Allied commanders sought to impose control as soon as they took the place of the retreating Germans.

However the PCI, under directives from Moscow, enabled the Allies to carry out their program of disarming the partisans and discouraged any revolutionary attempt at changing the social system.

Despite the pressing need to resolve social issues which persisted after the fall of fascism, the resistance movement was subordinated to the interests of Allied leaders in order to maintain the status quo.

With the city already held by resistance fighters, Mussolini used his connections one last time to secure passage with an escaping German convoy on its way to the Brenner Pass with his mistress Claretta Petacci.

[53] On the morning of 27 April 1945, Umberto Lazzaro (nom de guerre 'Partisan Bill'), a partisan with the 52nd Garibaldi Brigade, was checking a column of lorries carrying retreating SS troops at Dongo, Lombardy, near the Swiss border.

The date was chosen by convention, as it was the day of the year 1945 when the National Liberation Committee of Upper Italy (CLNAI) – whose command was based in Milan and was chaired by Alfredo Pizzoni, Luigi Longo, Emilio Sereni, Sandro Pertini, and Leo Valiani (present among others the designated president Rodolfo Morandi, Giustino Arpesani, and Achille Marazza) – proclaimed a general insurrection in all the territories still occupied by the Nazi-fascists, indicating to all the partisan forces active in Northern Italy that were part of the Volunteer Corps of Freedom to attack the fascist and German garrisons by imposing the surrender, days before the arrival of the Allied troops.

[79] Speaking at the 2014 anniversary, President Giorgio Napolitano said: "The values and merits of the Resistance, from the Partisan movement and the soldiers who sided with the fight for liberation to the Italian armed forces, are indelible and beyond any rhetoric of mythicization or any biased denigration.

The song originally aligned itself with Italian partisans fighting against Nazi German occupation troops, but has since become to merely stand for the inherent rights of all people to be liberated from tyranny.