Jürgen Ehlers

From graduate and postgraduate work in Pascual Jordan's relativity research group at Hamburg University, he held various posts as a lecturer and, later, as a professor before joining the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Munich as a director.

In 1995, he became the founding director of the newly created Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Potsdam, Germany.

He formulated a suitable classification of exact solutions to Einstein's field equations and proved the Ehlers–Geren–Sachs theorem that justifies the application of simple, general-relativistic model universes to modern cosmology.

He created a spacetime-oriented description of gravitational lensing and clarified the relationship between models formulated within the framework of general relativity and those of Newtonian gravity.

[2] Prior to Ehlers' arrival, the main research of Jordan's group had been dedicated to a scalar-tensor modification of general relativity that later became known as Jordan–Brans–Dicke theory.

[4] The group had a close working relationship with Otto Heckmann and his student Engelbert Schücking at Hamburger Sternwarte, the city's observatory.

[6] In 1970, Ehlers received an offer to join the Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics in Munich as the director of its gravitational theory department.

[8] Over the 24 years of his tenure, his research group was home to, among others, Gary Gibbons, John Stewart and Bernd Schmidt, as well as visiting scientists including Abhay Ashtekar, Demetrios Christodoulou and Brandon Carter.

[9] One of Ehlers' postdoctoral students in Munich was Reinhard Breuer, who later became editor-in-chief of Spektrum der Wissenschaft, the German edition of the popular-science journal Scientific American.

The institute started operations on 1 April 1995, with Ehlers as its founding director and as the leader of its department for the foundations and mathematics of general relativity.

[11] Ehlers then oversaw the founding of a second institute department devoted to gravitational wave research and headed by Bernard F. Schutz.

His principal concern was to clarify general relativity's mathematical structure and its consequences, separating rigorous proofs from heuristic conjectures.

He sought exact solutions of Einstein's equations: model universes consistent with the laws of general relativity that are simple enough to allow for an explicit description in terms of basic mathematical expressions.

However, general relativity is a fully covariant theory – its laws are the same, independent of which coordinates are chosen to describe a given situation.

[17] The first paper, written with Jordan and Kundt, is a treatise on how to characterize exact solutions to Einstein's field equations in a systematic way.

The work with Sachs studies, among other things, vacuum solutions with special algebraic properties, using the 2-component spinor formalism.

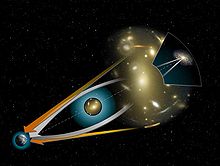

Spacetime geometry can influence the propagation of light, making them converge on or diverge from each other, or deforming the bundle's cross section without changing its area.

One result is the Ehlers-Sachs theorem describing the properties of the shadow produced by a narrow beam of light encountering an opaque object.

The paper systematically describes the basic concepts and models in what the editor of the journal General Relativity and Gravitation, on the occasion of publishing an English translation 32 years after the original publication date, called "one of the best reviews in this area".

At the time he started his research on his doctoral thesis, the Golden age of general relativity had not yet begun and the basic properties and concepts of black holes were not yet understood.

In the work that led to his doctoral thesis, Ehlers proved important properties of the surface around a black hole that would later be identified as its horizon, in particular that the gravitational field inside cannot be static, but must change over time.

The simplest example of this is the "Einstein-Rosen bridge", or Schwarzschild wormhole that is part of the Schwarzschild solution describing an idealized, spherically symmetric black hole: the interior of the horizon houses a bridge-like connection that changes over time, collapsing sufficiently quickly to keep any space-traveler from traveling through the wormhole.

This symmetry between the tt-component of the metric, which describes time as measured by clocks whose spatial coordinates do not change, and a term known as the twist potential is analogous to the aforementioned duality between E and B.

[27] In the 1970s, in collaboration with Ekkart Rudolph, Ehlers addressed the problem of rigid bodies in general relativity.

In contrast, the monograph developed a thorough and complete description of gravitational lensing from a fully relativistic space-time perspective.

For example, the frame theory can be used to show that the Newtonian limit of a Schwarzschild black hole is a simple point particle.

Ehlers participated in the discussion of how the back-reaction from gravitational radiation onto a radiating system could be systematically described in a non-linear theory such as general relativity, pointing out that the standard quadrupole formula for the energy flux for systems like the binary pulsar had not (yet) been rigorously derived: a priori, a derivation demanded the inclusion of higher-order terms than was commonly assumed, higher than were computed until then.

It is sponsored by the scientific publishing house Springer and is awarded triennially, at the society's international conference, to the best doctoral thesis in the areas of mathematical and numerical general relativity.