Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931)[1] is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, philosopher of science and Nobel Laureate in Physics.

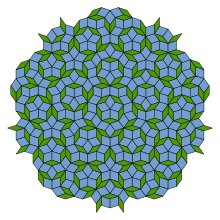

[28] As reviewer Manjit Kumar puts it: As a student in 1954, Penrose was attending a conference in Amsterdam when by chance he came across an exhibition of Escher's work.

Soon he was trying to conjure up impossible figures of his own and discovered the tribar – a triangle that looks like a real, solid three-dimensional object, but isn't.

Completing a cyclical flow of creativity, the Dutch master of geometrical illusions was inspired to produce his two masterpieces.

In 1964, while a reader at Birkbeck College, London, (and having had his attention drawn from pure mathematics to astrophysics by the cosmologist Dennis Sciama, then at Cambridge)[17] in the words of Kip Thorne of Caltech, "Roger Penrose revolutionised the mathematical tools that we use to analyse the properties of spacetime".

[31][32] Until then, work on the curved geometry of general relativity had been confined to configurations with sufficiently high symmetry for Einstein's equations to be solvable explicitly, and there was doubt about whether such cases were typical.

[33] The other, and more radically innovative, approach initiated by Penrose was to overlook the detailed geometrical structure of spacetime and instead concentrate attention just on the topology of the space, or at most its conformal structure, since it is the latter – as determined by the lay of the lightcones – that determines the trajectories of lightlike geodesics, and hence their causal relationships.

It also showed a way to obtain similarly general conclusions in other contexts, notably that of the cosmological Big Bang, which he dealt with in collaboration with Sciama's most famous student, Stephen Hawking.

[35][36][37] It was in the local context of gravitational collapse that the contribution of Penrose was most decisive, starting with his 1969 cosmic censorship conjecture,[38] to the effect that any ensuing singularities would be confined within a well-behaved event horizon surrounding a hidden space-time region for which Wheeler coined the term black hole, leaving a visible exterior region with strong but finite curvature, from which some of the gravitational energy may be extractable by what is known as the Penrose process, while accretion of surrounding matter may release further energy that can account for astrophysical phenomena such as quasars.

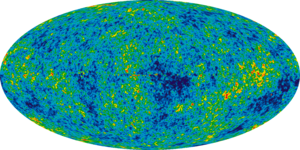

Also from 1979, dates Penrose's influential Weyl curvature hypothesis on the initial conditions of the observable part of the universe and the origin of the second law of thermodynamics.

[42] Penrose and James Terrell independently realised that objects travelling near the speed of light will appear to undergo a peculiar skewing or rotation.

[47] Another noteworthy contribution is his 1971 invention of spin networks, which later came to form the geometry of spacetime in loop quantum gravity.

[53][54] Penrose is the Francis and Helen Pentz Distinguished Visiting Professor of Physics and Mathematics at Pennsylvania State University.

[56] He mentions this evidence in the epilogue of his 2010 book Cycles of Time,[57] a book in which he presents his reasons, to do with Einstein's field equations, the Weyl curvature C, and the Weyl curvature hypothesis (WCH), that the transition at the Big Bang could have been smooth enough for a previous universe to survive it.

[58][59] He made several conjectures about C and the WCH, some of which were subsequently proved by others, and he also popularized his conformal cyclic cosmology (CCC) theory.

[60] In this theory, Penrose postulates that at the end of the universe all matter is eventually contained within black holes, which subsequently evaporate via Hawking radiation.

[62] One implication of this is that the major events at the Big Bang can be understood without unifying general relativity and quantum mechanics, and therefore we are not necessarily constrained by the Wheeler–DeWitt equation, which disrupts time.

)[68][69] Penrose believes that such deterministic yet non-algorithmic processes may come into play in the quantum mechanical wave function reduction, and may be harnessed by the brain.

He argues against the viewpoint that the rational processes of the mind are completely algorithmic and can thus be duplicated by a sufficiently complex computer.

Minsky's position is exactly the opposite – he believed that humans are, in fact, machines, whose functioning, although complex, is fully explainable by current physics.

Minsky maintained that "one can carry that quest [for scientific explanation] too far by only seeking new basic principles instead of attacking the real detail.

[74] Penrose and Hameroff have argued that consciousness is the result of quantum gravity effects in microtubules, which they dubbed Orch-OR (orchestrated objective reduction).

The reception of the paper is summed up by this statement in Tegmark's support: "Physicists outside the fray, such as IBM's John A. Smolin, say the calculations confirm what they had suspected all along.

[76] In January 2014, Hameroff and Penrose ventured that a discovery of quantum vibrations in microtubules by Anirban Bandyopadhyay of the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan[77] supports the hypothesis of Orch-OR theory.

[97] To quote the citation from the society: His deep work on General Relativity has been a major factor in our understanding of black holes.

His development of Twistor Theory has produced a beautiful and productive approach to the classical equations of mathematical physics.

[106] In 2020, Penrose was awarded one half of the Nobel Prize in Physics by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity, a half-share also going to Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy.