J. E. B. Stuart

While he cultivated a cavalier image (red-lined gray cape, the yellow waist sash of a regular cavalry officer, hat cocked to the side with an ostrich plume, red flower in his lapel, often sporting cologne), his serious work made him the trusted eyes and ears of Robert E. Lee's army and inspired Southern morale.

He obtained an appointment in 1850 to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, from Representative Thomas Hamlet Averett, the man who had defeated his father in the 1848 election.

While in Washington, D.C., to discuss government contracts, and in conjunction with his application for an appointment into the quartermaster department, Stuart heard about John Brown's raid on the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

While delivering Lee's written surrender ultimatum to the leader of the group, who had been calling himself Isaac Smith, Stuart recognized "Old Osawatomie Brown" from his days in Kansas.

[1] After early service in the Shenandoah Valley, Stuart led his regiment in the First Battle of Bull Run (where Jackson got his nickname, "Stonewall"), and participated in the pursuit of the retreating Federals, leading to sensationalist reports in the Northern press about the dreaded Confederate "black horse" cavalry.

Yet Stuart's self-confidence, penchant for action, deep love of Virginia, and total abstinence from such vices as alcohol, tobacco, and pessimism endeared him to Jackson.

[32] At the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas), Stuart's cavalry followed the massive assault by Longstreet's infantry against Pope's army, protecting its flank with artillery batteries.

By mid-afternoon, Stonewall Jackson ordered Stuart to command a turning movement with his cavalry against the Union right flank and rear, which if successful would be followed up by an infantry attack from the West Woods.

Stuart began probing the Union lines with more artillery barrages, which were answered with "murderous" counterbattery fire and the cavalry movement intended by Jackson was never launched.

[36] Three weeks after Lee's army had withdrawn back to Virginia, on October 10–12, 1862, Stuart performed another of his audacious circumnavigations of the Army of the Potomac, his Chambersburg Raid—126 miles in under 60 hours, from Darkesville, West Virginia to as far north as Mercersburg, Pennsylvania and Chambersburg and around to the east through Emmitsburg, Maryland and south through Hyattstown, Maryland and White's Ford to Leesburg, Virginia—once again embarrassing his Union opponents and seizing horses and supplies, but at the expense of exhausted men and animals, without gaining much military advantage.

As Lee began moving to counter this, Stuart screened Longstreet's corps and skirmished numerous times in early November against Union cavalry and infantry around Mountville, Aldie, and Upperville.

General Lee commended his cavalry, which "effectually guarded our right, annoying the enemy and embarrassing his movements by hanging on his flank, and attacking when the opportunity occurred."

[40] After Christmas, Lee ordered Stuart to conduct a raid north of the Rappahannock River to "penetrate the enemy's rear, ascertain if possible his position & movements, & inflict upon him such damage as circumstances will permit."

The astute Porter Alexander believed all credit was due: "Altogether, I do not think there was a more brilliant thing done in the war than Stuart's extricating that command from the extremely critical position in which he found it.

Jackson's wife, Mary Anna, wrote to Stuart on August 1, thanking him for a note of sympathy: "I need not assure you of which you already know, that your friendship & admiration were cordially reciprocated by him.

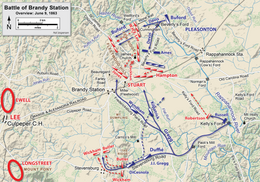

Six miles northeast, holding the line of the Rappahannock River, Stuart bivouacked his cavalry troopers, mostly near Brandy Station, screening the Confederate Army against surprise by the enemy.

Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock the next day and raid Union forward positions, screening the Confederate Army from observation or interference as it moved north.

In reaction, he ordered his cavalry commander, Major General Alfred Pleasonton, to take a combined arms force of 8,000 cavalrymen and 3,000 infantry on a "spoiling raid" to "disperse and destroy" the 9,500 Confederates.

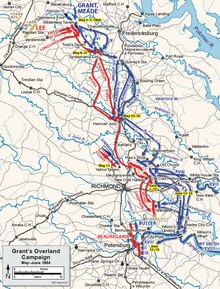

[54] Unfortunately for Stuart's plan, the Union army's movement was underway and his proposed route was blocked by columns of Federal infantry, forcing him to veer farther to the east than either he or General Lee had anticipated.

This prevented Stuart from linking up with Ewell as ordered and deprived Lee of the use of his prime cavalry force, the "eyes and ears" of the army, while advancing into unfamiliar enemy territory.

[61] During the retreat from Gettysburg, Stuart devoted his full attention to supporting the army's movement, successfully screening against aggressive Union cavalry pursuit and escorting thousands of wagons with wounded men and captured supplies over difficult roads and through inclement weather.

[63]One of the most forceful postbellum defenses of Stuart was by Colonel John S. Mosby, who had served under him during the campaign and was fiercely loyal to the late general, writing, "He made me all that I was in the war.

He wrote numerous articles for popular publications and published a book length treatise in 1908, a work that relied on his skills as a lawyer to refute categorically all of the claims laid against Stuart.

"[66] Although Stuart was not rebuked or disciplined in any official way for his role in the Gettysburg campaign, it is noteworthy that his appointment to corps command on September 9, 1863, did not carry with it a promotion to lieutenant general.

As Meade withdrew towards Manassas Junction, brigades from the Union II Corps fought a rearguard action against Stuart's cavalry and the infantry of Brigadier General Harry Hays's division near Auburn on October 14.

After the Confederate repulse at Bristoe Station and an aborted advance on Centreville, Stuart's cavalry shielded the withdrawal of Lee's army from the vicinity of Manassas Junction.

His defense at Laurel Hill, also directing the infantry of Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw, skillfully delayed the advance of the Federal army for nearly five critical hours.

[72] Sheridan moved aggressively to the southeast, crossing the North Anna River and seizing Beaver Dam Station on the Virginia Central Railroad, where his men captured a train, liberating 3,000 Union prisoners and destroying more than one million rations and medical supplies destined for Lee's army.

As he rode in pursuit, accompanied by his aide, Major Andrew R. Venable, they were able to stop briefly along the way to be greeted by Stuart's wife, Flora, and his children, Jimmie and Virginia.

The creation of the committee followed the circulation of a petition started by actress Julianne Moore and Bruce Cohen in 2016, which garnered over 35,000 signatures in support of changing the school's name to one honoring the late United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.