Overland Campaign

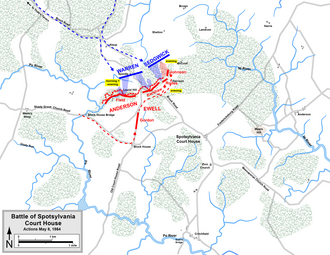

At the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House (May 8–21), Grant repeatedly attacked segments of the Confederate defensive line, hoping for a breakthrough but the only results were again many losses for both sides.

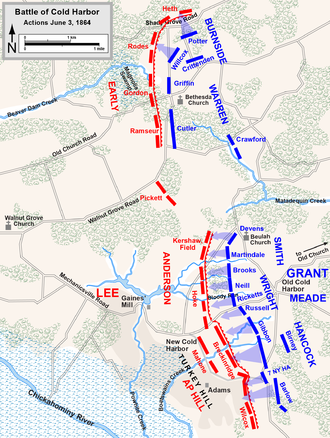

The final major battle of the campaign was waged at Cold Harbor (May 31 – June 12), in which Grant gambled that Lee's army was exhausted and ordered a massive assault against strong defensive positions, resulting in disproportionately heavy Union casualties.

Resorting to maneuver a final time, Grant surprised Lee by stealthily crossing the James River, threatening to capture the city of Petersburg, the loss of which would doom the Confederate capital.

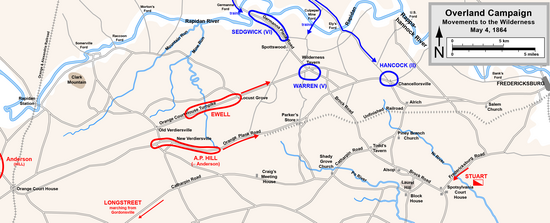

Grant and President Abraham Lincoln devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, Meade, and Benjamin Butler against Lee near Richmond, Virginia; Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama.

He meant to "hammer continuously against the armed force of the enemy and his resources until by mere attrition, if in no other way, there should be nothing left to him but an equal submission with the loyal section of our common country to the constitution and laws of the land."

Warren ordered an artillery section into Saunders Field to support his attack, but it was captured by Confederate soldiers, who were pinned down and prevented by rifle fire from moving the guns until darkness.

At 10 a.m., Longstreet's chief engineer reported that he had explored an unfinished railroad bed south of the Plank Road and that it offered easy access to the Union left flank.

Gordon's attack made good progress against inexperienced New York troops, but eventually the darkness and the dense foliage took their toll as the Union flank received reinforcements and recovered.

[32] Throughout the afternoon, Confederate engineers scrambled to create a new defensive line 500 yards further south at the base of the Mule Shoe, while fighting at the Bloody Angle continued day and night with neither side achieving an advantage.

Ewell fought near the Harris farm with several units of Union heavy artillery soldiers who had recently been converted to infantry duty before he was recalled by Lee.

James H. Wilson's men were initially pushed back in some confusion, but Gregg had concealed a heavy line of skirmishers armed with repeating carbines in a brushy ravine.

From a strategic standpoint, however, the raid deprived General Grant of the cavalry resources that would have been helpful at Spotsylvania Court House and his subsequent advance to the North Anna River, and there are lingering questions about whether Sheridan should have attempted to assault the city of Richmond.

In the latter case, Sheridan believed it would not have been worth the risk in casualties and he recognized that the chances of holding the city for more than a brief time would be minimal; any advantages would primarily result from damage to Confederate morale.

He and his chief engineer devised a solution: a five-mile (8 km) line that formed an inverted "V" shape with its apex on the river at Ox Ford, the only defensible crossing in the area.

"[51] The only visible opposition to the Union crossing was at Ox Ford, which Grant interpreted to be a rear guard action, and ordered Burnside's IX Corps to deal with it.

"[56] One of a series of protective outposts guarding supply lines for Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's Bermuda Hundred Campaign was a fort at Wilson's Wharf, at a strategic bend in the James River in eastern Charles City, overlooked by high bluffs.

[60] As he did after the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Grant now planned to leave the North Anna in another wide swing around Lee's flank, marching east of the Pamunkey River to screen his movements from the Confederates.

Lee, who was still in his tent suffering from the diarrhea that had incapacitated him during the North Anna battle, was fooled by Grant's actions and assumed that the Union general would be moving west for the first time in the campaign.

They advanced through a severe crossfire of rifle and cannon fire and were able to close within 50 yards of the Union position before Willis was mortally wounded and the brigade fell back to its starting point.

If Smith moved due west from White House Landing to Cold Harbor, 3 miles southeast of Bethesda Church and Grant's left flank, the extended Federal line would be too far south for the Confederate right to contain it.

[84] While action continued on the southern end of the battlefield, the three corps of Hancock, Burnside, and Warren were occupying a 5-mile line that stretched southeast to Bethesda Church, facing the Confederates under A.P.

The most effective performance of the day was on the Union left flank, where Hancock's corps was able to break through a portion of Breckinridge's front line and drive those defenders out of their entrenchments in hand-to-hand fighting.

He launched a powerful assault at 6 a.m. that overran the Confederate skirmishers but mistakenly thought he had pierced the first line of earthworks and halted his corps to regroup before moving on, which he planned for that afternoon.

The trenches were hot, dusty, and miserable, but conditions were worse between the lines, where thousands of wounded Federal soldiers suffered horribly without food, water, or medical assistance.

[96] At dawn on June 11, Hampton devised a plan in which he would split his divisions across the two roads leading to Clayton's Store and converge on the enemy at that crossroads, pushing Sheridan back to the North Anna River.

Eventually Col. Gilbert J. Wright's Confederate brigade joined in the close-quarter fighting in the thick brush, but after several hours they also were pushed back within sight of Trevilian Station.

He also received intelligence that Breckinridge's infantry had been sighted near Waynesboro, effectively blocking any chance for further advance, so he decided to abandon his raid and return to the main army at Cold Harbor.

Having been blocked by Hampton's cavalry, Sheridan withdrew on June 25 and moved through Charles City Court House to Douthat's Landing, where the trains crossed the James on flatboats.

Now, Grant selected a geographic and political target and knew that his superior resources could besiege Lee there, pin him down, and either starve him into submission or lure him out for a decisive battle.

He made mistakes, but the overall pattern of his campaign reveals an innovative general employing thoughtful combinations of maneuver and force to bring a difficult adversary to bay on his home turf.