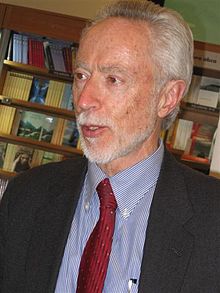

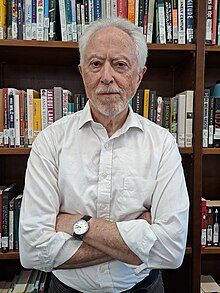

J. M. Coetzee

John Maxwell Coetzee[a] FRSL OMG (born 9 February 1940) is a South African and Australian novelist, essayist, linguist, translator and recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature.

[4][5] His father was often absent, and enlisted in the army and fought in World War II to avoid being prosecuted on a criminal charge.

[8][9] His mother's grandfather was a Pole, referred to by the Germanised form, Balthazar du Biel, but actually born Balcer Dubiel in 1844 in the village of Czarnylas (Schwarzwald), in a part of Poland annexed by Prussia.

[4] From as early as 1968, Coetzee sought permanent residence in the U.S., a process that was finally unsuccessful, in part due to his involvement in protests against the war in Vietnam.

[4] In 1972, Coetzee returned to South Africa and was appointed lecturer in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Cape Town.

He has also written autobiographical novels, short fiction, translations from Dutch and Afrikaans, and numerous essays and works of criticism.

[41] When awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy stated that Coetzee "in innumerable guises portrays the surprising involvement of the outsider".

[42] The press release for the award also cited his "well-crafted composition, pregnant dialogue and analytical brilliance", while focusing on the moral nature of his work.

[61] In 2013, Richard Poplak of the Daily Maverick called Coetzee "inarguably the most celebrated and decorated living English-language author".

[63][20] In 2010, Coetzee was made an international ambassador for Adelaide Writers' Week, along with American novelist Susanna Moore and English poet Michael Hulse.

It was called "the culmination of an enormous collaborative effort and the first event of its kind in Australia" and "a reflection of the deep esteem in which John Coetzee is held by Australian academia".

[71][72] According to Fred Pfeil, Coetzee, André Brink and Breyten Breytenbach were at "the forefront of the anti-apartheid movement within Afrikaner literature and letters".

It is exactly the kind of literature you would expect people to write from prison", and called on the South African government to abandon its apartheid policy.

[49] The scholar Isidore Diala wrote that Coetzee, Nadine Gordimer, and Brink are "three of South Africa's most distinguished white writers, all with definite anti-apartheid commitment".

[76] After his Australian citizenship ceremony, Coetzee said: "I did not so much leave South Africa, a country with which I retain strong emotional ties, but come to Australia.

I came because from the time of my first visit in 1991, I was attracted by the free and generous spirit of the people, by the beauty of the land itself and—when I first saw Adelaide—by the grace of the city that I now have the honour of calling my home.

[78] When Coetzee won the Nobel Prize, Mbeki congratulated him "on behalf of the South African nation and indeed the continent of Africa".

South African author Nadine Gordimer suggested that Coetzee had "a revulsion against all political and revolutionary solutions", and he has been both praised for his condemnation of racism in his writing and criticised for not explicitly denouncing apartheid.

"[82] The main character in Coetzee's 2007 book Diary of a Bad Year, which has been described as blending "memoir with fiction, academic criticism with novelistic narration" and refusing "to recognize the border that has traditionally separated political theory from fictional narrative",[83] shares similar concerns about the policies of John Howard and George W.

[85] In a speech given on his behalf by Hugo Weaving in Sydney on 22 February 2007, Coetzee railed against the modern animal husbandry industry.

[88] In 2008, at the behest of John Banville, who alerted him to the matter, Coetzee wrote to The Irish Times of his opposition to Trinity College Dublin's use of vivisection on animals for scientific research.

"[89] Nearly nine years later, when TCD's continued (and, indeed, increasing) practice of vivisection featured in the news, a listener to the RTÉ Radio 1 weekday afternoon show Liveline pointed out that Banville had previously raised the matter but been ignored.

Banville then telephoned Liveline to call the practice "absolutely disgraceful" and recalled how his and Coetzee's efforts to intervene had been to no avail: "I was passing by the front gates of Trinity one day and there was a group of mostly young women protesting and I was interested.

Some lady professor from Trinity wrote back essentially saying Mr. Banville should stick to his books and leave us scientists to our valuable work."

[93][94] The aim of the seminars, one observer remarked, was "to develop comparative perspectives on the literature" and journalism of the three areas, "to establish new intellectual networks, and to build a corpus of translated works from across the South through collaborative publishing ventures".

[95] He developed an interest in Argentine literature, and curated a series for the publishing house El Hilo de Ariadna, which includes Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Samuel Beckett's Watt, and Patrick White's The Solid Mandala.

[28][97] When asked in 2015 to address unofficial Iranian translations of foreign works — Iran does not recognize international copyright agreements — Coetzee stated his disapproval of the practice on moral grounds and wished to have it sent to journalistic organisations in that country.

[99] The series produces limited-edition signed works by literary greats to raise money for the child victims and orphans of the African HIV/AIDS crisis.

[100] Coetzee has mentioned a number of literary figures who, like him, have tried "to transcend their national and historical contexts": Rainer Maria Rilke, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, T.S.

[77][102] The South African writer Rian Malan, in oft-quoted words from an article published in the New Statesman in 1999, called Coetzee "a man of almost monkish self-discipline and dedication", and reported—based on hearsay—that he rarely laughed or even spoke.