Japan Air Lines Flight 123

[2] Japan's Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission (AAIC),[3]: 129 assisted by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board,[4] concluded that the structural failure was caused by a faulty repair by Boeing technicians following a tailstrike seven years earlier.

When the faulty repair eventually failed, it resulted in a rapid decompression that ripped off a large portion of the tail and caused the loss of all hydraulic systems and the flight controls.

[1] On June 2, 1978, while operating Japan Air Lines Flight 115 along the same route, JA8119 bounced heavily on landing while carrying out an instrument approach to runway 32L at Itami Airport.

The cockpit crew consisted of: The flight was during the Obon holiday period when many Japanese people make trips to their hometowns or to resorts.

[3]: 22 They were Yumi Ochiai, an off-duty flight attendant; Hiroko and Mikiko Yoshizaki, a mother and her 8-year-old daughter; and Keiko Kawakami, a 12-year-old girl who lost her parents and sister in the crash.

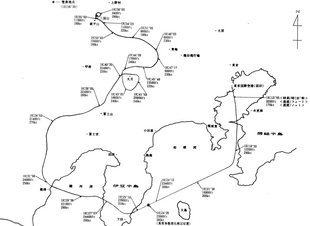

[3]: 17 [8] Twelve minutes after takeoff, at 6:24 p.m., at near cruising altitude over Sagami Bay 3.5 miles (3.0 nmi; 5.6 km) east of Higashiizu, Shizuoka, the aircraft underwent rapid decompression,[3]: 83 bringing down the ceiling around the rear lavatories, damaging the unpressurised fuselage aft of the plane, unseating the vertical stabilizer, and severing all four hydraulic lines.

Captain Takahama ordered First Officer Sasaki to reduce the bank angle,[3]: 296 and expressed confusion when the aircraft did not respond to the control wheel being turned left.

Captain Takahama declined Tokyo Control's suggestion to divert to Nagoya Airport 72 nautical miles (83 mi; 133 km) away, instead preferring to land at Haneda, which had the facilities to handle the 747.

The unpressurised aircraft rose and fell in an altitude range of 20,000–25,000 feet (6,100–7,600 m) for 18 minutes, from the moment of decompression until around 6:40 p.m., with the pilots seemingly unable to figure out how to descend without flight controls.

[3]: 1–6 This was possibly due to the effects of hypoxia at such altitudes, as the pilots seemed to have difficulty comprehending their situation as the aircraft pitched and rolled uncontrollably.

The accident report indicates that the captain's disregard of the suggestion is one of several features "regarded as hypoxia-related in [the] CVR record[ing].

"[3]: 97 Their voices can be heard relatively clearly on the cockpit area microphone for the entire duration, until the crash, indicating that they did not put on their oxygen masks at any point in the flight.

[3]: 96, 126 At 6:35 p.m. the flight engineer responded to multiple (hitherto unanswered) calls from Japan Air Tokyo via the SELCAL (selective-calling) system.

Japan Air Tokyo asked if they intended to return to Haneda, to which the flight engineer responded that they were making an emergency descent, and to continue to monitor them.

"[3]: 89 Shortly after 6:40 p.m., they lowered the landing gear using the emergency extension system in an attempt to dampen the phugoid cycles and Dutch rolls further.

Possibly in order to prevent another stall, at 6:51 p.m., the captain lowered the flaps to 5 units—due to the lack of hydraulics, using an alternate electrical system—in an additional attempt to exert control over the stricken jet.

The leading edge flaps except for the left and right outer groups were also extended and the extension was completed at 6:52:39 p.m.[3]: 291 [20] From 6:49:03 to 6:52:11 p.m., Japan Air Tokyo attempted to call the aircraft again via the SELCAL radio system.

[21][3]: 326–27 The aircraft continued an unrecoverable right-hand descent toward the mountains as the bank angle recovered to about 70° and engines were pushed to full power, during which the ground proximity warning system sounded.

[3]: 292 The aircraft was still in a 40° right-hand bank when the right-most (#4) engine struck the trees on top of a ridge located 1.4 kilometres (0.87 mi) north-northwest of Mount Mikuni at an elevation of 1,530 metres (5,020 ft), which can be heard on the CVR recording.

It is speculated that this impact separated the remainder of the weakened tail from the airframe, along with the outer third of the right wing, and the remaining three engines, which were "dispersed 500–700 metres (1,600–2,300 ft) ahead".

[3]: 123, 127 [13] The aircraft crashed at an elevation of 1,565 metres (5,135 ft) in Sector 76, State Forest, 3577 Aza Hontani, Ouaza Narahara, Ueno Village, Tano District, Gunma Prefecture.

[22] An article in the Pacific Stars and Stripes from 1985 stated that personnel at Yokota were on standby to help with rescue operations, but were never called by the Japanese government.

Instead, they were dispatched to spend the night at a makeshift village erecting tents, constructing helicopter landing ramps, and engaging in other preparations, 63 kilometres (39 miles) from the crash site.

"[8] One of the four survivors, off-duty Japan Air Lines flight purser Yumi Ochiai (落合 由美, Ochiai Yumi) recounted from her hospital bed that she recalled bright lights and the sound of helicopter rotors shortly after she awoke amid the wreckage, and while she could hear screaming and moaning from other survivors, these sounds gradually died away during the night.

[20] The official cause of the crash according to the report published by Japan's Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission is: In an unrelated incident on 19 August 1982, while under the control of the first officer, JA8119 suffered a runway strike of the No.

[3]: 102 The Japanese public's confidence in Japan Air Lines took a dramatic downturn in the wake of the disaster, with passenger numbers on domestic routes dropping by one-third.

Rumors persisted that Boeing had admitted fault to cover up shortcomings in the airline's inspection procedures, thereby protecting the reputation of a major customer.

On August 12, 2010, for the 25th anniversary of the accident, Japan Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism Minister Seiji Maehara visited the site to remember the victims.

[31] Families of the victims, together with local volunteer groups, hold an annual memorial gathering every August 12 near the crash site in Gunma Prefecture.

The center has displays regarding aviation safety, the history of the crash, and selected pieces of the aircraft and passenger effects (including handwritten farewell notes).