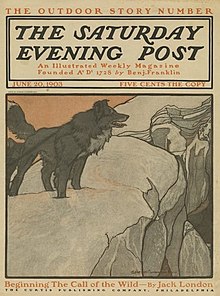

The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild is a short adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand.

The story opens at a ranch in Santa Clara Valley, California, when Buck is stolen from his home and sold into service as a sled dog in Alaska.

By the end, he sheds the veneer of civilization, and relies on primordial instinct and learned experience to emerge as a leader in the wild.

The story opens in 1897 with Buck, a powerful 140-pound St. Bernard–Scotch Shepherd mix,[1][2] happily living in California's Santa Clara Valley as the pampered pet of Judge Miller and his family.

One night, assistant gardener Manuel, needing money to pay off gambling debts, steals Buck and sells him to a stranger.

Over the next several weeks on the trail, a bitter rivalry develops between Buck and the lead dog, Spitz, a vicious and quarrelsome white husky.

When François and Perrault complete the round-trip of the Yukon Trail in record time, returning to Skagway with their dispatches, they are given new orders from the Canadian government.

Meanwhile, the weary animals become weak from the hard labor, and the wheel dog, Dave, a morose husky, becomes terminally sick and is eventually shot.

With the dogs too exhausted and footsore to be of use, the mail carrier sells them to three stampeders from the American Southland (the present-day contiguous United States)—a vain woman named Mercedes, her sheepish husband Charles, and her arrogant brother Hal.

They lack survival skills for the Northern wilderness, struggle to control the sled, and ignore others' helpful advice—particularly warnings about the dangerous spring melt.

Buck pulls a sled with a half-ton (1,000 lb; 450 kg) load of flour, breaking it free from the frozen ground, dragging it 100 yards (91 m), and winning Thornton US$1,600 (equivalent to $59,000 in 2023).

"[3] While Thornton and his two friends pan gold, Buck hears the call of the wild, explores the wilderness, and socializes with a wolf from a local pack.

To reach the goldfields, he and his party transported their gear over the Chilkoot Pass, often carrying loads as heavy as 100 pounds (45 kg) on their backs.

With his companions, he rafted 2,000 miles (3,200 km) down the Yukon River, through portions of the wildest territory in the region, until they reached St. Michael.

He submitted a query letter to the San Francisco Bulletin proposing a story about his Alaskan adventure, but the idea was rejected because, as the editor told him, "Interest in Alaska has subsided to an amazing degree.

At the time, London was criticized for attributing "unnatural" human thoughts and insights to a dog, so much so that he was accused of being a nature faker.

Also, I endeavored to make my stories in line with the facts of evolution; I hewed them to the mark set by scientific research, and awoke, one day, to find myself bundled neck and crop into the camp of the nature-fakers.

"[24]Along with his contemporaries Frank Norris and Theodore Dreiser, London was influenced by the naturalism of European writers such as Émile Zola, in which themes such as heredity versus environment were explored.

As with other characters of American literature, such as Rip van Winkle and Huckleberry Finn, Buck symbolizes a reaction against industrialization and social convention with a return to nature.

[27] The enduring appeal of the story, according to American literature scholar Donald Pizer, is that it is a combination of allegory, parable, and fable.

[16] As a writer, London tended to skimp on form, according to biographer Labor, and neither The Call of the Wild nor White Fang "is a conventional novel".

[34] Writing in the "Introduction" to the Modern Library edition of The Call of the Wild, E. L. Doctorow says the theme is based on Darwin's concept of the survival of the fittest.

Pizer describes how the story reflects human nature in its prevailing theme of strength, particularly in the face of harsh circumstances.

[27] Gianquitto writes that in Buck's characterization, London created a type of Nietzschean Übermensch – in this case a dog that reaches mythic proportions.

The stanza outlines one of the main motifs of The Call of the Wild: that Buck when removed from the "sun-kissed" Santa Clara Valley where he was raised, will revert to his wolf heritage with its innate instincts and characteristics.

The imagery and symbolism in the first phase, to do with the journey and self-discovery, depict physical violence, with strong images of pain and blood.

[33] The harshness, brutality, and emptiness in Alaska reduce life to its essence, as London learned, and it shows in Buck's story.

"[4] A reviewer for The New York Times wrote of it in 1903: "If nothing else makes Mr. London's book popular, it ought to be rendered so by the complete way in which it will satisfy the love of dog fights apparently inherent in every man.

"[42] The reviewer for The Atlantic Monthly wrote that it was a book: "untouched by bookishness...The making and the achievement of such a hero [Buck] constitute, not a pretty story at all, but a very powerful one.

[36] The first printing of 10,000 copies sold out immediately; it is still one of the best-known stories written by an American author and continues to be read and taught in schools.