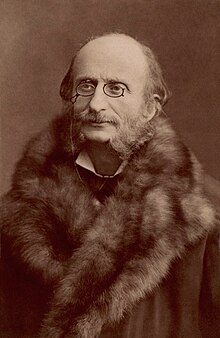

Jacques Offenbach

In 1858 Offenbach produced his first full-length operetta, Orphée aux enfers ("Orpheus in the Underworld"), with its celebrated can-can; the work was exceptionally well received and has remained his most played.

The risqué humour (often about sexual intrigue) and mostly gentle satiric barbs in these pieces, together with Offenbach's facility for melody, made them internationally known, and translated versions were successful in Vienna, London, elsewhere in Europe and in the US.

With generous support from local music lovers and the municipal orchestra, with whom they gave a farewell concert on 9 October, the two young musicians, accompanied by their father, made the four-day journey to Paris in November 1833.

[49] He amused the comtesse de Vaux's 200 guests with a parody of Félicien David's currently fashionable Le désert, and in April 1846 gave a concert at which seven operatic items of his own composition were premiered before an audience that included leading music critics.

[56] The composer and critic Claude Debussy later wrote that the musical establishment could not cope with Offenbach's irony, which exposed the "false, overblown quality" of the operas they favoured – "the great art at which one was not allowed to smile".

[15][58] In The Musical Quarterly, Martial Teneo and Theodore Baker wrote, "Without the example set by Hervé, Offenbach might perhaps never have become the musician who penned Orphée aux Enfers, La belle Hélène, and so many other triumphant works.

[71] With a text translated and adapted by Léon Battu and Ludovic Halévy, he presented it during the Mozart centenary celebrations in May 1856 as L'impresario; it was popular with the public[85] and also greatly enhanced the critical and social standing of the Bouffes-Parisiens.

[88][90] Although the Bouffes-Parisiens played to full houses, the theatre was constantly on the verge of running out of money, principally because of what his biographer Alexander Faris calls "Offenbach's incorrigible extravagance as a manager".

He condemned the piece for profanity and irreverence to Roman mythology: the theme was the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, although Napoleon III and his government were generally seen as the real targets of its satire.

Gammond lists among the reasons for its success, "the sweeping waltzes" reminiscent of Vienna but with a new French flavour, the patter songs, and "above all else, of course, the can-can which had led a naughty life in low places since the 1830s or thereabouts and now became a polite fashion, as uninhibited as ever".

Of Offenbach's new pieces, Geneviève de Brabant, though initially only a mild success, was later revised and gained much popularity; the comedy duet of the two cowardly gendarmes became a favourite number in Britain as well as France and the basis for the Marines' Hymn in the US.

Offenbach, who called them "Meil" and "Hal",[110] said of this trinity: "Je suis sans doute le Père, mais chacun des deux est mon Fils et plein d'Esprit,"[111] a play on words loosely translated as "I am certainly the Father, but each of them is my Son and Wholly Spirited".

[112] Rehearsals for the premiere at the Théâtre des Variétés were tempestuous, with Schneider and the principal mezzo-soprano Léa Silly feuding, the censor fretting about the satire of the imperial court, and the manager of the theatre attempting to rein in Offenbach's extravagance with production expenses.

La Vie parisienne later in the same year was a new departure for Offenbach and his librettists; for the first time in a large-scale piece they chose a modern setting, instead of disguising their satire under a classical cloak.

Ernest Guiraud, a family friend, assisted by Offenbach's 18-year-old son Auguste, completed the orchestration, making major changes as well as the substantial cuts demanded by the Opéra-Comique's director, Carvalho.

He was given a state funeral; The Times reported, "The crowd of distinguished men that accompanied him on his last journey amid the general sympathy of the public shows that the late composer was reckoned among the masters of his art.

He could write straightforward "singing" numbers like Paris's song in La belle Hélène, "Au mont Ida trois déesses" [Three goddessess on Mount Ida]; comic songs like General Boum's "Piff Paff Pouf" and the ridiculous ensemble at the servants' ball in La vie parisienne, "Votre habit a craqué dans le dos" ["Your coat has split down the back"].

[158] Within these conventional limits, he employed greater resource in his varied use of rhythm; in a single number he would contrast rapid patter for one singer with a broad, smooth phrase for another, illustrating their different characters.

[164] In Keck's view, "Offenbach's orchestral scoring is full of details, elaborate counter-voices, minute interactions coloured by interjections of the woodwinds or brass, all of which establish a dialogue with the voices.

"[170] Another lyric set to absurdly ceremonious music is "Votre habit a craqué dans le dos" (your coat has split down the back) in La vie parisienne.

[156] Offenbach followed suit in a series of twenty operettas; the conductor and musicologist Antonio de Almeida names the finest of these as La fille du tambour-major (1879).

[174] The critic Tim Ashley writes, "Stylistically, the opera reveals a remarkable amalgam of French and German influences ... Weberian chorales preface Hoffmann's narrative.

[190] The two creators of the Savoy operas – the librettist, Gilbert, and the composer, Sullivan – were both indebted to Offenbach and his partners for their satiric and musical styles, even borrowing plot components.

[192][n 25] The best-known instance in which a Savoy opera draws on Offenbach's work is The Pirates of Penzance (1879), where both Gilbert and Sullivan follow the lead of Les brigands (1869) in their treatment of the police, who plod along ineffectually in heavy march-time.

The libretto for Die Fledermaus was adapted from a play by Meilhac and Halévy,[199] and the operetta specialist Richard Traubner comments that Strauss was influenced by "the two brilliant party scenes" in Offenbach's La vie parisienne.

[200] A leading Viennese critic demanded that composers "remain within the realm of pure operetta, a rule strictly observed by Offenbach",[198] and among Strauss's later stage works was Prinz Methusalem (1877), described by Lamb as "a satirical Offenbachian piece".

[203] Suppé's Das Pensionnat (The Boarding School, 1860) not only emulates Offenbach, but refers to him in the first act, when the heroine, the schoolgirl Sophie, and her friends learn about the can-can and proceed to dance it.

[205] In the Cambridge Opera Journal in 2014 the musicologist Micaela Baranello writes that Franz Lehár's operettas have a strong Offenbachian element, alongside what she calls a "folksy, imaginary" Mitteleuropan one.

"[217] The New York Times shared this view: "That he had the gift of melody in a very extraordinary degree is not to be denied, but he wrote currente calamo,[n 28] and the lack of development of his choicest inspirations will, it is to be feared, keep them from reaching even the next generation".

"[229] In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Lamb writes:[4] His opera Les contes d'Hoffmann has retained a place in the international repertory, but his most significant achievements lie in the field of operetta.