Jaekelopterus

In overall appearance, Jaekelopterus is similar to other pterygotid eurypterids, possessing a large, expanded telson (the hindmost segment of the body) and enlarged pincers and forelimbs.

The chelicerae and compound eyes of Jaekelopterus indicate it was active and powerful with high visual acuity, most likely an apex predator in the ecosystems of Early Devonian Euramerica.

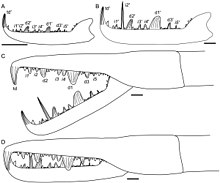

[1] Jaekelopterus is similar to other pterygotid eurypterids in its overall morphology,[2] distinguished by its triangular telson (the hindmost segment of its body) and inclined principal denticles on its cheliceral rami (the moving part of the claws).

[6] Jaekelopterus was originally described as a species of Pterygotus, P. rhenaniae, in 1914 by German palaeontologist Otto Jaekel based on an isolated fossil pretelson (the segment directly preceding the telson) he received that had been discovered at Alken in Lower Devonian deposits of the Rhineland in Germany.

[10] In 1974, Størmer erected a new family to house the genus, Jaekelopteridae, due to the supposed considerable differences between the genital appendage of Jaekelopterus and other pterygotids.

[9] This diverging feature has since been proven to simply represent a misinterpretation by Størmer in 1936, the genital appendage of Jaekelopterus in fact being unsegmented like that of Pterygotus.

[9] Another species of Pterygotus, P. howelli, was named by American palaeontologist Erik Kjellesvig-Waering and Størmer in 1952 based on a fossil telson and tergite (the dorsal part of a body segment) from Lower Devonian deposits of the Beartooth Butte Formation in Wyoming.

The species name howelli honours Dr. Benjamin Howell of Princeton University, who loaned the fossil specimens examined in the description to Kjellesvig-Waering and Størmer.

Based on some similarities in the genital appendage, American palaeontologists James C. Lamsdell and David A. Legg suggested in 2010 that Jaekelopterus, Pterygotus and even Acutiramus could be synonyms of each other.

[2] Though differences have been noted in chelicerae, these structures were questioned as the basis of generic distinctions in eurypterids by Charles D. Waterston in 1964 since their morphology is dependent on lifestyle and varies throughout ontogeny (the development of the organism following its birth).

Lamsdell and Legg concluded that an inclusive phylogenetic analysis with multiple species of Acutiramus, Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus is required to resolve whether the genera are synonyms of each other.

[1] The cladogram also contains the maximum sizes reached by the species in question, which was suggested to possibly have been an evolutionary trait of the group per Cope's rule ("phyletic gigantism") by Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie.

Even tergites and sternites (the plates that form the surfaces of the abdominal segments) are generally preserved as paper-thin compressions, suggesting that pterygotids were very lightweight in construction.

[18] Like all other arthropods, eurypterids matured through a sequence of stages called "instars" consisting of periods of ecdysis (moulting) followed by rapid growth.

Unlike many arthropods, such as insects and crustaceans, chelicerates (the group to which eurypterids like Jaekelopterus belongs, alongside other organisms such as horseshoe crabs, sea spiders and arachnids) are generally direct developers, meaning that there are no extreme morphological changes after they have hatched.

[3] Though several fossilised instars of Jaekelopterus howelli are known, the fragmentary and incomplete status of the specimens makes it difficult to study its ontogeny in detail.

[19] Both Jaekelopterus rhenaniae and Pterygotus anglicus had high visual acuity, as suggested by the low IOA and many lenses in their compound eyes.

Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie considered in a 2007 study that it was highly unlikely that an arthropod with the size and build of Jaekelopterus would be able to walk on land.

[9] The chelicerae of Jaekelopterus are enlarged, robust and have a curved free ramus and denticles of different lengths and sizes, all adaptations that correspond to strong puncturing and grasping abilities in extant scorpions and crustaceans.

Some puncture wounds on fossils of the poraspid agnathan fish Lechriaspis patula from the Devonian of Utah were likely caused by Jaekelopterus howelli.

[19] Fully grown Jaekelopterus would have been apex predators in their environments and likely preyed upon smaller arthropods (including resorting to cannibalism) and early vertebrates.

The hydromechanics of the swimming paddles and telsons of Jaekelopterus and other pterygotids suggest that all members of the group were capable of hovering, forward locomotion and quick turns.