Eurypterus

See text Baltoeurypterus Størmer, 1973 Eurypterus (/jʊəˈrɪptərəs/ yoo-RIP-tər-əs) is an extinct genus of eurypterid, a group of organisms commonly called "sea scorpions".

The name means 'wide wing' or 'broad paddle', referring to the swimming legs, from Greek εὐρύς (eurús 'wide') and πτερόν (pteron 'wing').

[2] However, De Kay thought Eurypterus was a branchiopod (a group of crustaceans which include fairy shrimps and water fleas).

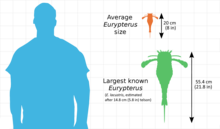

[10] In the introduction page of E. remipes in website of University of Texas at Austin says that the largest specimen ever found was 1.3 m (4.3 ft) long, currently on display at the Paleontological Research Institution of New York.

[2][12] The prosoma is the forward part of the body, it is actually composed of six segments fused together to form the head and the thorax.

[13] They also possessed two smaller light-sensitive simple eyes (the median ocelli) near the center of the carapace on a small elevation (known as the ocellar mound).

Each of the segments of the postabdomen contain lateral flattened protrusions known as the epimera with the exception of the last needle-like (styliform) part of the body known as the telson.

Its ventral segments are overlaid by appendage-derived plates known as Blattfüsse (singular Blattfuss, German for "sheet foot").

The main respiratory organs of Eurypterus were what seems to be book gills, located in branchial chambers within the segments of the mesosoma.

In addition, they also possessed five pairs of oval-shaped areas covered with microscopic projections on the ceiling of the second branchial chambers within the mesosoma, immediately below the gill tracts.

As a consequence, nearly every remotely similar eurypterid in the 19th century was classified under the genus (except for the distinctive members of the family Pterygotidae and Stylonuridae).

[5] In 1958, several species distinguishable by closer placed eyes and spines on their swimming legs were split off into the separate genus Erieopterus by Erik Kjellesvig-Waering.

[5] Another split was proposed by Leif Størmer in 1973 when he reclassified some Eurypterus to Baltoeurypterus based on the size of some of the last segments of their swimming legs.

It is now believed that the minor variations described by Størmer are simply the differences found in adults and juveniles within a species.

Modeling studies on Eurypterus swimming behavior suggest that they utilized a drag-based rowing type of locomotion where appendages moved synchronously in near-horizontal planes.

[29] An alternative hypothesis for Eurypterus swimming behavior is that individuals were capable of underwater flying (or subaqueous flight), in which the sinuous motions and shape of the paddles themselves acting as hydrofoils are enough to generate lift.

[24][31] Juveniles probably swam using the rowing type, the rapid acceleration afforded by this propulsion is more suited for quickly escaping predators.

[31][32] Trace fossil evidence indicates that Eurypterus employed a rowing stroke when in close proximity to the seafloor.

[33] Arcuites bertiensis is an ichnospecies that includes a pair of crescent-shaped impressions and a short medial drag, and it has been found in upper Silurian eurypterid Lagerstatten in Ontario and Pennsylvania.

The morphology of A. bertiensis suggests that Eurypterus had the ability to move its swimming appendages in both the horizontal and vertical plane.

They utilized the mass of spines on their front appendages to both kill and hold them while they used their chelicerae to rip off pieces small enough to swallow.

Juveniles were likely to have inhabited nearshore hypersaline environments, safer from predators, and moved to deeper waters as they grew older and larger.

Adults that reach sexual maturity would then migrate en masse to shore areas in order to mate, lay eggs, and molt.

[12] Examinations of the respiratory systems of Eurypterus have led many paleontologists to conclude that it was capable of breathing air and walking on land for a short amount of time.

These structures were supported by semicircular 'ribs' and were probably attached near the center of the body, similar to the gills of modern horseshoe crabs.

[35][25] During this period, the landmasses were mostly restricted to the southern hemisphere of the Earth, with the supercontinent Gondwana straddling the South Pole.

The equator had three continents (Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia) which slowly drifted together to form the second supercontinent of Laurussia (also known as Euramerica, not to be confused with Laurasia).

[3] The ancestors of Eurypterus were believed to have originated from Baltica (eastern Laurussia, modern western Eurasia) based on the earliest recorded fossils.

During the Silurian, they spread to Laurentia (western Laurussia, modern North America) when the two continents began to collide.

[6] Eurypterus are very common fossils in their regions of occurrence, millions of specimens are possible in a given area, though access to the rock formations may be difficult.