Jaffa–Jerusalem railway

The project was headed by Joseph Navon, an Ottoman Jewish entrepreneur from Jerusalem, after previous attempts by the British-Jewish philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore failed.

[7] After examining two possible routes, he deemed a rail line to Jerusalem too expensive, estimating construction costs at 4,000–4,500 pounds per kilometer.

[8] Chesney did not give up, contacting Sir Arthur Slade, a general in the Ottoman army, who supported the plan for a railway in what is today Iraq.

[9] According to another account, Montefiore backed out of the project when Culling Eardley reiterated during a meeting that the railway would serve Christian missionary activity.

[12] The German architect and city engineer Conrad Schick, a Jerusalem resident, later published a similar booklet, where he also detailed his own proposal for a railway, which called for a line through Ramallah and Beit Horon.

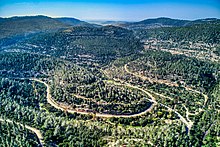

[6] A route along the lines of Schick's plan was for a long time considered the most viable, and French engineers conducted an extensive survey to that end in 1874–75.

Navon's chief partners and endorsers included his cousin Joseph Amzalak, the Greek Lebanese engineer George Franjieh, and the Swiss Protestant banker Johannes Frutiger.

He tried to raise more funds, including from Theodor Herzl, although the latter was not interested and wrote that it was a "wretched little line from Jaffa to Jerusalem [which] was of course quite inadequate for our needs.

"[26] The groundbreaking ceremony took place on March 31, 1890, in Yazur, attended by the governor of Palestine, Ibrahim Hakkı Pasha, the Grand Mufti of Gaza, Navon, Frutiger, etc.

[27] The track was chosen to be of 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge, similarly to French minor railways, and was brought in from France and the Belgian manufacturer Angleur.

Bulky, but light articles, such as boiler barrels or water tanks, were thrown into the sea and tugged ashore; all other materials had to be landed by lighters.

[39] Yosef Navon, who had already been awarded the French Legion of Honor for his involvement in the railway,[16] received a Turkish medal, and in 1895 or 1896—the title of Bey.

[1] In A Practical Guide to Jerusalem and its Environs, a guidebook written around that time, E. A. Reynolds-Ball wrote: "It requires only an ordinary amount of activity to jump out and pick the flowers along the line, and rejoin the train as it laboriously pants up the steep ascent — a feat I myself have occasionally performed.

The line showed an overall growth trend between 1896 and World War I, impeded mainly by the Sixth cholera pandemic which spread to Palestine in 1902 and again in 1912, and the increasingly nationalistic Ottoman authorities.

[56] When the British advanced northwards in November 1917, the railway was sabotaged by Austrian saboteurs from the retreating Central Powers army and most (five) of its bridges were blown up.

[60] In February 1918, a Decauville 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge railway was built from Jaffa to Lydda, with an extension to the Auja River, the front line at the time.

[61][62] This extension was furthered to the Arab village al-Jalil (today the Glilot area), and continued to be used until 1922–23 mainly for transporting construction materials, without locomotives.

[68] The final section, between Jaffa and Lydda, was completed in September 1920, and inaugurated in a ceremony attended by Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner, on October 5.

The High Commissioner, writing to the Colonial Office, emphasized that "it is an integral part of the scheme that the Railway between Jaffa and Jerusalem should be electrified and that the electric energy for the line should be supplied by the Concessionaire."

Following the 1949 Armistice Agreements, the entire route was returned to Israel, and officially restarted operations on August 7, 1949, when the first Israeli train, loaded with a symbolic shipment of flour, cement and Torah scrolls, arrived at Jerusalem.

Even though in the late 1950s Israel Railways began using diesel locomotives, and repaired the line, it did not convert it to a dual-track configuration and travel time was still high.

The reasons cited were the fact that the line was causing traffic jams in the city, and the high land value of the area for real estate development.

The railroad suffered numerous terrorist attacks during the 1960s prior to the Six-Day War, especially due to its proximity to the Green Line and the Arab village Battir.

[82] This improved conditions and timetable reliability in the first section, which a variety of train types could now traverse, but significantly increased the time between Jerusalem and destinations other than Beit Shemesh,[83] and the line was re-united in the following seasonal schedule.

The rebuilding process itself was also criticized, because a number of historic structures were destroyed, including the original Beit Shemesh and Bittir stations, and a stone bridge.

[84] Work has continued to improve the line between Na'an and Beit Shemesh by straightening curves and replacing level crossings with bridges.

This section is planned to be widened to quadruple-track in the future and besides trains to Beit Shemesh and Jerusalem, it also serves the lines to Ashkelon (via Lod and Rehovot), Ben Gurion Airport, and Beersheba.

[90] Selah Merrill, in Scribner's Magazine, notes that the real significance of the railway's construction wasn't the 86.5 km of track laid, but the fact that it was done in the Ottoman Empire, which according to him had been attempting at all costs to keep out Western civilization.

In the first decade of the line's existence the population of the city almost doubled, which is all the more amazing when considering that Jerusalem at this period produced hardly enough wine, vegetables or cattle for its own needs.

[94] The line prompted Eliezer Ben Yehuda to write a poem about it, and to coin the words Rakevet (רַכֶּבֶת, "train") and Katar (קַטָּר, "locomotive") for the Hebrew language, suggested by Yehiel Michel Pines and David Yellin, respectively.